I am very excited to have Michelle Gagnon as my guest, but she is definitely no stranger to TKZ. Many of you know Michelle was a former contributor extraordinaire to our blog and I’m excited to hear her thoughts on trilogies and her latest release. Welcome, Michelle!

Hi folks, I’ve missed you! So good to be back on TKZ.

With the success of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Hunger Games, trilogies are all the rage these days. In fact, when I first pitched an idea for a young adult novel to my publisher, they specifically requested a trilogy. I agreed, because hey, what author wouldn’t want to guarantee the publication of three more books? Besides, I’d written a series before. How much harder could a trilogy be?

The first one, DON’T TURN AROUND, turned out to be the easiest book I’ve ever written. The rough draft flowed out of me in eight weeks; it was one of those magical manuscripts that seemed to write itself.

I sat back down at the computer, confident that the second and third would proceed just as smoothly; even (foolishly) harboring hopes that I’d knock the whole thing out in under six months.

Boy, was I wrong.

Here’s the thing: in a regular series, even though the characters carry through multiple books (and occasionally, plotlines do as well), they’re relatively self-contained. In the end, the villain is (usually) captured or killed; at the very least, his evil plan has been stymied.

Not so in a trilogy. For this series, I needed the bad guy—and the evil plot—to traverse all three books. Yet each installment had to be self-contained enough to satisfy readers.

Suffice it to say that books 2 and 3 were a grueling enterprise. But along the way, I learned some important lessons on how to structure a satisfying trilogy:

So those are my tips, earned the hard way. Today’s question: what trilogies (aside from those I mentioned) did you love, and what about them kept you reading?

Michelle Gagnon is the international bestselling author of thrillers for teens and adults. Described as “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo meets the Bourne Identity,” her YA technothriller DON’T TURN AROUND was nominated for a Thriller Award, and was selected as one of the best teen books of the year by Entertainment Weekly Magazine, Kirkus, Voya, and the Young Adult Library Services Association. The second installment, DON’T LOOK NOW, is on sale now (and hopefully doesn’t suffer from “middle book syndrome.”) She splits her time between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Michelle Gagnon is the international bestselling author of thrillers for teens and adults. Described as “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo meets the Bourne Identity,” her YA technothriller DON’T TURN AROUND was nominated for a Thriller Award, and was selected as one of the best teen books of the year by Entertainment Weekly Magazine, Kirkus, Voya, and the Young Adult Library Services Association. The second installment, DON’T LOOK NOW, is on sale now (and hopefully doesn’t suffer from “middle book syndrome.”) She splits her time between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

One of the words I’ve been repeating in my works lately has been “dark”. You know, the man swung his dark gaze her way. He wore a dark suit. He had his dark hair brushed back over a wide forehead. Shadows darkened in a corner as he gave her a dark scowl.

Ouch.

This can be considered lazy writing, except I hadn’t even been aware of this fault until I ran one of the self-edit programs described in my personal blog at http://bit.ly/12iU9nZ. I embarked on a search and find mission to replace as many of these weak terms as possible.

Let’s start with clothes. Face it, men wear dark suits. To get a better idea of colors, I accessed this website: http://lawyerist.com/suit-colors-for-the-clueless/. Ah, now it became clear which colors are popular for men and suited to business. My descriptions of dark suits changed to black, charcoal, slate or navy. That’s a lot better than “dark”, isn’t it?

If you want to get even more particular, go online to a department store site like Macys.com and put in the search feature “suits, “blazers”, or “sportcoats” and you’ll get a wide variety of colors.

What about the character who has dark hair? Is it black or dark brown? Check this reference:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_hair_color. Instead of black hair, give your character raven, ebony, or onyx hair. Varying the descriptions adds spice to your story.

Also watch out for redundancies like dark shadows & dark scowl. Both of these work well without the “dark” element.

Despite its ambiguity, this word is popular for movies. Witness Batman’s The Dark Knight; Thor: The Dark World; and Star Trek into Darkness.

The filmmakers can get away with it, but as a writer, you cannot. What other ambiguous words like this might you want to change?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

A friend alerted me this past week to an interesting “infographic” posted on Goodreads. The subject: Why readers abandon a book they’ve started. Among the reasons:

– Weak writing

– Ridiculous plot

– Unlikable main character

But the #1 reason by far was: Slow, boring.

Makes sense, doesn’t it? As I’ve stated here before, there is at least one “rule” for writing a novel, and that is Don’t bore the reader!

So if I may channel my favorite commercial character, The Most Interesting Man in the World:

Find out the things readers don’t like, then . . . don’t do those things.

I thank you.

Okay, let’s have a closer look.

Weak Writing

This probably refers to pedestrian or vanilla-sounding prose. Unremarkable. Without what John D. MacDonald called “unobtrusive poetry.” You have to have a little style, or what agents and editors refer to as “voice.” I’ll have more to say about voice next week. But for now, concentrate on reading outside your genre. Or read poetry, like Ray Bradbury counseled. Simply get good wordsmithing into your head. This will expand your style almost automatically.

Ridiculous Plot

Thriller writers are especially prone to this. I remember picking up a thriller that starts off with some soldiers breaking into a guy’s house. He’s startled! What’s going on? Jackboots! In my house! Why? Because, it turns out, the captain wants him for some sort of secret meeting. But I thought, why send a crack team of trained soldiers to bust into one man’s suburban home and scare the living daylights out of him? Especially when they know he’s no threat to anyone. No weapons. No reason to think he’d resist. And why wake up the entire neighborhood (a plot point conveniently ignored)? Why not simply have a couple of uniforms politely knock on the door and ask the guy to come with them? The only reason I could think of was that the author wanted to start off with a big, cinematic, heart-pounding opening. But the thrills made no sense. I put the book down.

Every plot needs to have some thread of plausibility. The more outrageous it is, the harder you have to work to justify it. So work.

Unlikable Main Character

The trick to writing about a character who is, by and large, unlikable (i.e., does things we generally don’t approve of) is to give the reader something to hang their hat on. Scarlett O’Hara, for example, has grit and determination. Give readers at least one reason to hope the character might be redeemed.

Slow, Boring

The biggie. There is way too much to talk about here. I’ve just concluded a 3-day intensive workshop based, like just about everything I do, on what I call Hitchcock’s Axiom. When asked what makes a compelling story he said that it is “life, with the dull parts taken out.”

If I was forced to put general principles in the form of a telegram, I’d say:

Create a compelling character and put him in a “death match” with an opponent (the death being physical, professional, or psychological) and only write scenes that in some way reflect or impact that battle.

The principle is simple and straightforward. Learning how to do it takes time, practice and study, which you can start right now, today.

So what about you? What makes you put a book down? And related to that, do you feel compelled, most of the time, to finish a book you start? I used to, but now I don’t. Life’s too short, and there are too many books on my TBR list!

INTERFACE (a thriller)

First Page Critique

Tom Faraday awoke feeling like he had been sleeping forever, and immediately struggled to recall where he was, or how he had got there. Some nights, he reflected, you hope you remember. Others you hope you forget. Tom was not sure which category the previous night would crystallise under. Right now he was just feeling the after effects of what must have been an evening of extraordinary excess.

He rolled over in the hotel bed and blinked repeatedly. The alarm clock read 8:30 a.m. Next to the clock was his watch, and next to that an electronic card key for his room. Picking it up he saw he was at the Western Star Hotel, in Waterloo, central London. This seemed vaguely familiar, but a stabbing pain deep in his head was making it hard to think clearly. He slipped on his watch, a present from his mother, slid out of bed and padded across to where his suitcase lay open. From a small zipped compartment he retrieved paracetamol and swallowed them down with gulps from a bottle of mineral water. He then stumbled into the bathroom, and was greeted by a tired visage in the mirror. His eyes were bloodshot, hair unkempt, stubble unusually obvious. He stroked his chin distractedly, thinking he must have forgotten to shave the previous day.

Back on the desk he found an elegantly printed invitation, and as he read it his memories started to return. The card bore his name in calligraphic handwriting, and was to the launch party for CERUS Technologies’ new office building. Tom rubbed his eyes and thought hard. What did he know?

He knew his name. He knew his age: 26. He remembered his job. He was a lawyer at CERUS Technologies. And he remembered the party.

He remembered getting there by taxi, late on Friday night. He remembered William Bern’s speech. And he remembered drinking a few beers. And then a few more. Perhaps a lot more. Of the trip back to the hotel, he remembered nothing. Friday night had come and gone.

He stretched slowly and looked for another bottle of water. Apart from the headache he did not feel too bad. Hopefully no harm done, and the rest of the weekend to recover. The noise of a mobile phone ringing broke him from his thoughts. His phone. He retrieved it from his pocket, noticing the battery was nearly dead.

<><><>

Critique by Nancy J. Cohen

The opening line is great. It immediately draws me in, wondering the same thing as the character. Where is he, and what is he doing there? I would delete “he reflected.” We’re in his viewpoint, and that qualifier is unnecessary.

Crystallize has a “z” not an “s”.

Delete the “just” before “just feeling.” This is one of those overused words. For more info in this regard, please see my review of a fabulous self-editing program at http://bit.ly/12iU9nZ. The Smart-Edit software points out all the words and phrase you overuse and much more.

What kind of drug is paracetamol?

I’d separate into a new paragraph, “The noise of a mobile phone…”

The cell phone is in his pocket? Is he still wearing his clothes from the night before? Or did he get dressed in them?

So the guy is hungover from a workplace party. I’m intrigued, but I am wondering where this is going. Hopefully the caller will inject more information. You do point of view very well, and I have no problems with the pacing especially if a dialogue ensues.

At first, I thought Tom had memory loss and couldn’t remember how he got where he is. But he does seem to recall everything, except maybe the cab ride back to the hotel. Then again, where does he normally live? My questions tell you I am hooked and would read more. I’d be hoping, though, that something happens to tell me all isn’t right and things are going to get hairier from here on in. Good job and Happy Fourth of July!

Do you ever put a book down if you’ve read a few chapters and can’t go farther? This rarely happens with me, but I can recall a couple of instances where I gave up. Normally, I’ll slog through and scan pages until the end, if the story holds any appeal at all. But sometimes it’s too tedious to continue and a waste of precious time. What are some of the reasons why we might stop reading?

Too Many Characters

The book I’m reading now is one I really want to like. It’s science fiction with a strong female lead and starts off on a spaceship. I know her mission is about to go terribly wrong. The woman’s lover is an alien, and I can understand his race’s characteristics. But then we meet other crew members and a diplomatic contingent from another world. Numerous other races are introduced, and the author segues into multiple viewpoints. Now I’m getting lost. I can’t keep track of all the aliens with weird sounding names. If the story doesn’t focus on the protagonist and her human emotions, I may put this book aside.

My own first published novel employed multiple viewpoints and alien races. But since the story stayed mostly inside the heads of my hero/heroine and focused on their romance, the world building seemed to work. I won the HOLT Medallion Award with Circle of Light, so I wasn’t alone in my assessment.

Yet the current book I’m reading is just too confusing. I’m losing interest in the story because it’s too hard to keep the alien characters straight.

A mystery can have similar problems when too many suspects are introduced at the same time. I’ve been guilty of this myself, whether it is a dinner party or cocktail event or other affair which all of the suspects attend together. One chapter might contain a blast of characters, whereas the sleuth’s subsequent investigation focuses on one at a time. It’s hard to avoid this dilemma when all of the important characters appear together in a scene toward the book’s beginning.

Book Doesn’t Stand Alone

I picked up a book mid-series by a popular author whose work I wanted to read. The opening scenes left me totally lost. If you hadn’t read the previous books, you were clueless. A writer should never assume readers have followed along with her series. Each book should stand alone with enough explanations to cover previous subplots. On the other hand, this requires a delicate balance. You don’t want to bore your fans with repetitious material. Nor do you want to repeat what happened in previous installments unless it’s relevant to the current story.

Genre Lacks Appeal

I’ve judged contests where I have to read entries in a genre other than ones I prefer. I do my best to be fair, but if the story is peppered every paragraph with naughty words, for example, that’s going to turn me off. At that point, I’ll skim through the book. That’s why in my leisure reading choices, I stick to genres I know and love.

Story Meanders

Too many boring scenes where conversation acts as filler or the plot fails to advance will make me lose interest. Here I might skip ahead to get to the scenes where something happens.

Incomprehensible Language

If I am reading science fiction or fantasy and the world building includes too many made up words, I might get lost and lose interest. Every other noun doesn’t have to sound futuristic. Ditto for historical novels where the dialects are so strong as to be annoying.

Unlikeable Characters

I’ll rarely give up on a book because I don’t like the characters. These stories I might skim through to see if there’s a redeeming factor. But if I really don’t like the people, that might be cause to put the book down.

As a writer, keep these points in mind so you don’t make the same mistakes in your work. No doubt we’re all guilty to some extent, but try to avoid these pitfalls whenever possible.

So what are some reasons why you might not continue reading a story?

James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

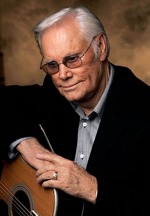

Last Friday, a giant in country music passed away. George Jones was not only considered by many to be the greatest country singer of all time, but also one of the most self-destructive. His string of hits was fueled by a private life of booze that was nothing short of  devastating. Once when his wife hid the car keys so he couldn’t go buy alcohol, he hopped on a riding lawn mower and rode it into town to the liquor store. He later parodied the story in a music video.

devastating. Once when his wife hid the car keys so he couldn’t go buy alcohol, he hopped on a riding lawn mower and rode it into town to the liquor store. He later parodied the story in a music video.

But despite the long chain of events that few mortals could survive, George Jones climbed to the top of the mountain and made a place for himself that will forever be the gold standard in country music.

His life was a soap opera that was mirrored in the songs he sang. His struggles with the demons of alcoholism are reflected in some of his album titles: “The Battle”, “Bartender’s Blues”, and the defiant “I Am What I Am”. But out of this self-inflicted carnage of a tragic life, one song emerged as arguably the greatest country song ever written: “He Stopped Loving Her Today”.

The song is performed with the singer telling the story of his "friend" who has never given up on his love. He keeps old letters and photos, and hangs on to hope that she would "come back again." The song reaches its peak with the chorus, telling us that he indeed stopped loving her – when he finally died.

It’s poignant, sad, and paints a heart-wrenching portrait of absolute love and devotion, as well as never-ending hope. Not only does it drill to the core of emotion, but it delivers the story with the few words.

So what does this have to do with writing books? Everything.

It’s called the economy of words—telling the most story with the least amount of text. It is an art form that songwriters must master, and novelists must study. There is no better example of the economy of words than in a song like ‘He Stopped Loving Her Today’. Not one word is wasted. No filler. No fluff. Remove or change a word from the song and the mental picture starts to deflate. The story is told in the most simplistic manner and the result is a masterpiece. Every word is chosen for its optimal emotional impact. Nothing is there that shouldn’t be. It is a grand study in how to write anything.

I’m not suggesting that your 100K-word novel be written with the intensity of George Jones’ song. In fact, if it were, it would probably be too overwhelming to comprehend. But my point is that no matter who you are—New York Times bestseller or wannabe author, your book contains too many unnecessary words. If you can say it in 5 instead of 10, do it. Get rid of the filler and fluff. Respect the economy of words. Less is more.

For those that love George Jones, enjoy this video. For those that have not heard “He Stopped Loving Her Today”, click the link, listen and learn.

He Stopped Loving Her Today by George Jones