James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I had an exquisite experience the other day, the kind we as readers love, but we as writers don’t find often enough, namely: I got so caught up in a novel I lost the realization that I was reading at all. I was pulled into the fictive dream and did not want to put the book down. I set everything else aside so I could finish the book.

I can’t remember the last time that happened. Usually when I read fiction part of my mind is analyzing it: Why is the author doing that? Does this metaphor work? Why am I thinking of putting the book down? Ooh, that was a neat technique, I need to remember it . . .

This time, though, I was fully into the story. It was only when I finished the book that I took a breath and asked myself, What just happened? Why was I so caught up? What did this author do right?

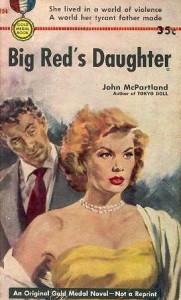

The novel is Big Red’s Daughter. It’s a 1953 Gold Medal paperback original. I found it when I was poking around the internet for 40s and 50s noir. I love that period because the plotting is often superb, the writing workmanlike to excellent, and the effect every bit as suspenseful as anything written today—without the need for gratuitous language or description of body parts. The sexual tension was suggested, even on the book covers. Oh, those covers! Love ’em. I was drawn to this one:

And then I looked at the author’s name. I didn’t know him. So I did a little research and found out there’s . . . very little research available on John McPartland. I love discovering little-known authors, and McPartland certainly qualifies. So how pleased was I when I got the book and had this “can’t put it down” experience?

I’m not claiming that this is a novel that should have won the Pulitzer. But it is a prime example of what pulp and paperback writers of that era had to do to eat: write entertaining, fast moving, popular fiction.

They knew the craft of storytelling. Since I teach it and take it apart myself, I was anxious to try to discover what McPartland brought to Big Red’s Daughter. Here’s what I found:

1. A decent guy just trying to find his place in the world

Jim Work is a Korea veteran, back home now and about to go to college on the G. I. Bill. The returning vet trying to find his place is a vintage post-war noir theme, one the reading audience couldn’t get enough of. He wants a job. Wants to get along. Wants to find a girl and get married.

For a page-turner, you have to have a Lead character readers are not just going to care about, but root for. Even if you’re writing about a negative Lead (e.g., Scrooge) the audience has got to find something possibly redeeming.

Jim Work is not perfect. Readers don’t respond to that. But we are on his side, because he yearns to do the right things.

2. The trouble starts on page one

Here’s the first paragraph:

HE WAS DRIVING AN MG—a low English-built sports car— and he was a tire-squeaker, the way a wrong kind of guy is apt to be in a sports car. I heard the squeal of his tires as he gunned it, and then I saw him cutting in front of me like a red bug. My car piled into his and the bug turned over, spilling him and the girl with him out onto the street.

Turns out the other guy and girl are not hurt. The guy walks over to Jim and sucker punches him. He’s about to stomp Jim’s face into hamburger when the girl who was with him grabs him from behind.

The guy’s name is Buddy Brown. The girl is Wild Kearney (her real name. Love it!) And immediately Jim is drawn to her—another noir trope. She is a “bronze-blonde” but “looked like the kind of girl that would be with winners, not losers, top winners in the top tournaments and never the second-flight or the almost-good-enough. Not the kind of girl that I’d ever known.”

So here we have both violence and potential romance from the start. And the Lead is vulnerable in both toughness and love.

The rule here is simple: Don’t warm up your engines. Get the reader turning the page not because he’s patient with you, but because he needs to find out what is going to happen next!

3. Unpredictability

Buddy Brown seems to calm down, and invites Jim out to a house where some other people are having a party. Suddenly, this Brown fellow seems like he might be okay. Jim goes along, because of Wild. And because he has a desire to work Brown over for the sucker punch, and maybe to start the process of getting the girl away from him.

Brown’s behavior throughout the book is unpredictable, but with an undercurrent of danger. He’s like a snake that could bite at any moment, but at other times seems friendly. You’re just not sure what he’s going to do next, because he is . . .

4. A nasty but charming bad guy

Buddy Brown is ruthless and sadistic, yet able to charm the ladies and the gents. At the house party Jim calls him a “punk,” and Brown says he is going to kill Jim for that remark. Jim tries to fight him again and Brown beats him up, but good. We get the sense Buddy could kill Jim without a second thought, but then he relents and is charming again. In Hitchcock thrillers the most charming character is often the bad guy (see, e.g., Joseph Cotton in Shadow of a Doubt and Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train). Such a character is much more interesting than a one-note evil villain. Which leads to . . .

5. Sympathy for the bad guy

Dean Koontz is big on this. You put in just enough backstory to understand why a guy would turn out this way. The cross-currents of emotion in a reader are experienced rather than analyzed, and that’s a good thing. Great fiction is, above all, an emotional ride.

In one scene, Jim finds Buddy drunk and stumbling around, because he knows Big Red Kearney (Wild’s tough-guy father) wants to hunt him down and kill or ruin him. Jim, in a display of 1950s loyalty to his species (sober men take care of drunken men), takes Buddy into a place for coffee. Buddy tells him a little of his backstory. When he was fifteen, growing up in New York, he and two friends got on the bad side of a local gang leader:

He looked across the booth at me, his bruised, pale face a little twisted.

“Mick and me, we run off from home. The boys came to my house and worked over my old man to tell where I was. He didn’t know, so they gave him the big schlammin. He’s never going to get over it. They caught Mick downtown somewhere and they took him out on Long Island, tied him up with wire, and burned him. You know, with gasoline. He was a very sharp kid, good dancer, lot of laughs when he was high on sticks. He got burned up.”

The slender, drunken boy was talking in his soft whisper, his eyes far away from mine, talking with a clear earnestness as if he were living it all again.

“I’ve never forgotten that year. I hid down near the produce market, sleeping in the daytime, going out at night to scrounge rotten fruit and stuff. The big rats would be out at night and I’d carry a stick and a sack of rocks. For two months I hid like that. Then it cleared up. The wheel got sent up for armed robbery and the other guys forgot about it. But I remember that year.”

Suddenly Buddy is humanized. Not that he’s any less dangerous. Our emotional involvement in the story thus deepens.

6. A spiral of trouble

In the first two chapters this guy Jim has a car accident, gets punched in the face, is drawn to another man’s girl, goes to a party where he gets in another fight with Buddy, and ends up badly beaten and bloody.

And this is the good part of his next couple of days.

It’s a classic example of things just getting worse and worse as they go along.

7. A love triangle

Between Wild, Buddy and Jim. And while we’re on the subject, want to see how the best writers wrote about sex back then? Here is the only sex scene in the book, in its entirety:

I swung the car to the right on the rutted road over the dune, toward the surge of the waters of the bay.

It was a finding without a knowing. There had been a typhoon in Tokyo once when the wood-and-paper buildings ripped before the fury. This was a typhoon between two people––a man and a woman who thought she belonged to another man.

Then it was a knowing as enemies who were once friends might know each other.

After that it was a silence between two people who should not have been silent. We both knew now, we understood each other. We should not have been silent in that way. At last I held her in my arms again, and there was no storm, but there were no words.

We don’t need body parts, do we?

8. A crisp style

McPartland’s style never gets in the way of the narrative. He doesn’t strain for effect, and the resulting emotions are rendered naturally, sharply. After the sex scene described above, Jim takes Wild home.

She opened the door and was outside the car.

I was out and we stood there together. I brought her to me, but she was not with me. A tall girl in my arms, a lovely girl, a girl behind a frozen wall, a girl who did not speak.

Wild stood there after I put my arms down, and then there was a kiss, and we were close and warm there in the darkness, kissing as lovers do when the good-by could be forever. Perhaps Wild thought it would be.

It was over, still without words, and she went down the steps and pushed open the door. There was a rectangle of soft light just before the door closed behind her.

I was halfway in the car when I heard the scream.

Do you want to read on? I think you do.

9. A relentless pace with a tightening noose

The action of the story is compressed into a couple of days, so it really moves. Any time you can put time pressure on your characters (the “ticking clock”) it’s a good thing. And the stakes, as I argue in my plotting books, have to be death (physical, professional or psychological). In Big Red’s Daughter,it’s physical. A noose (Jim is accused of murder) is tightening around the Lead’s neck.

In the midst of the action there are emotional beats, too. But these never bog down the story, only deepen it. At one point Jim is put in a jail cell. Here is the longest emotional beat in the book:

The night loneliness engulfed me. I thought of Buddy Brown.

They’d find him somewhere tonight. Walking on a dark street between the hills. In his bed. Sitting alone in his room with a bottle. Sitting alone and laughing, with the brown cigarette cupped in his hand, the weed-sweet smell thick in the room. Maybe now an officer, hand on his holstered gun, was walking toward Buddy Brown in the lonely Greyhound waiting room at Salinas while the heavy-eyed soldiers and huddled Mexicans watched. Maybe a state highway patrol car was flagging down the MG on 101. Night thoughts. Night thoughts on a bunk, scratching flea bites.

They wouldn’t find him. It was a night truth, one of those things that you know as you lie awake toward dawn. Maybe they’d look for him, but they wouldn’t find him.

I moved restlessly on the sagging bunk.

10. Honor

In Revision & Self-Editing for Publication, I have a section called “The Secret Ingredient: Honor.” I think we are hard-wired to look for honor in others, and to want to act honorably ourselves when the chips are down. When Big Red Kearney shows up in the story, there is a bond of honor that he strikes with Jim, recognizing that Jim is not a punk like Buddy Brown. When this bond happens it makes you root for Jim all the more.

11. A resonant ending

I won’t describe what it is, lest people want to read the book. The last chapter is short, doing its job. There is no anti-climax. And for my money, it ends just right, with what I call resonance. It’s that feeling of satisfaction that the last note is perfect and extends in the air after you close the book.

I work on my endings more than any part of my stories. I want to leave the reader feeling like the whole trip has been worth it, right up to and including the very last line. I will sometimes re-write my last pages ten, twenty, even thirty times.

So there you have it. I’m not saying these eleven items are the only way to write a page-turner, but if you could get all of them in a book, that result would be practically guaranteed.