by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

A pole vaulter doesn’t come out of the locker room, pick up a pole, and get to vaulting. Like all athletes, they warm up. They do some stretching, some sprinting, test the poles, do a few practice vaults.

A pole vaulter doesn’t come out of the locker room, pick up a pole, and get to vaulting. Like all athletes, they warm up. They do some stretching, some sprinting, test the poles, do a few practice vaults.

That’s how writers should view morning pages. They warm you up so you can reach new heights when you write. The subject has come up in comments several times here at TKZ, so I thought I’d offer some of the different ways I’ve personally done morning pages.

Bradbury’s Landmine

The great Ray Bradbury, in his book Zen in the Art of Writing, said of his morning pages: “Every morning I jump out of bed and step on a landmine. The landmine is me. After the explosion, I spend the rest of the day putting the pieces together.”

He explained that by writing down what was in his brain the first thing upon waking, was capturing whatever dreams had percolated, or whatever his subconscious decided to tell him. He didn’t try to make sense of it as he wrote. The idea was to pour it all out, see what was there, and only then look for a story possibility.

Robert Louis Stevenson often got plot ideas in his dreams. In the wee small hours one morning, his wife was awakened by cries of horror from her husband. Thinking he was having a nightmare, she wakened him. He angrily said, “Why did you awaken me? I was dreaming a fine bogey tale!” He got up and began writing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Natalie Goldberg’s Non-Stop Writing

In her book Writing Down the Bones, Natalie Goldberg advocates “writing practice” before getting to your WIP. You simply pick a starter (like “I remember…” or “describe the light coming through your window,” or “write about an early memory”) and just go without stopping, without editing, without judgment. Follow wherever your writing leads you. The idea is to learn to free yourself up as you write anything.

Additionally, Goldberg advises doing this exercise for distinct moments in your fiction—especially description. You come to a point where you’re going to describe a character, or place, or clothing…whatever. You pause and open a new document and write for five minutes on that one thing, letting your mind feed you images and metaphors. (Now there’s AI to do that work for you. Personally, I don’t like that. Using our own neural networks exercises our brains…which we need if for nothing else than to fight the machines!)

Julia Cameron’s Morning Pages

In The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron describes morning pages as “three pages of longhand writing, strictly stream-of-consciousness.” Even though my handwriting is awful, I think there is something to using pen or pencil on paper that exercises parts of your brain not normally brought out to play.

My variation on this is to do page-long sentences. No worries about grammar or punctuation, just letting one word lead to another and following any rabbit trail that comes up. It’s all about loosening up the creative muscles before the pole vault of your WIP.

Writing the Natural Way

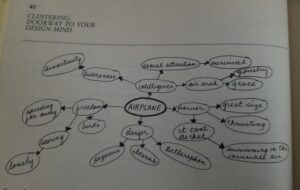

In Writing the Natural Way, Gabriele Lusser Rico champions “clustering” as a way to unleash the right brain. Clustering is also known as mind mapping. You use a pen or pencil on blank paper, and start with a word or phrase in the middle of the page. Put a circle around it. Then start putting down words that connect to the main word, and connections from the new words, until you have a whole page of circled words or phrases with lines between them.

Let the map sit for awhile, then bring some form to it. I put numbers by certain words in priority order. I find this especially helpful when I’m mapping out a nonfiction article or book. It results in a usable outline. But I’ve also used this for big scenes in my novels.

Micro and Flash Fiction

Use a writing prompt to write a short-short story. Flash fiction is under 1k words; micro fiction is under 250 (though some purists make it under 100). I’ve written before about Storymatic. There’s also Writer Igniter that shuffles various elements for you.

Think about the prompt for a minute or two. You may stay with it, or you can tweak it. There’s no wrong way to approach this. I try to envision an opening scene and an ending to work toward. Then I write it. I share the best of these on my Patreon page. But even the ones I don’t use are of benefit, as the value of this exercise is in the effort.

Sue Grafton’s Novel Journal

The author of the famous alphabet series featuring PI Kinsey Millhone, Sue Grafton, began each writing day by jotting in what she called her novel journal. She’d first put something down about how she felt that day, and then record any ideas that occurred to her “in the dead of night, when Shadow and Right Brain are most active.” Finally, she’d reflect on where she was in the book, ask What if? She’d write down many possible directions, and assess them later. (No surprise she was a pantser…but this also works for plotters, who can fill out details in scenes, deepen emotions, find happy surprises, including metaphors.)

So, ready to jump into your writing day? Warm up with morning pages, then set your bar high.

What are your thoughts on morning pages?

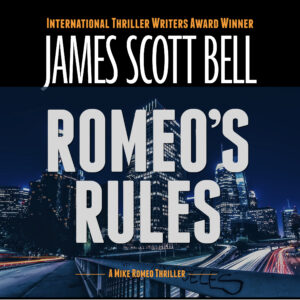

A note for you audio book fans. Romeo’s Rules, the first book in my Mike Romeo thriller series, has just come out in audio.

We’ve talked in the past about doing some of our writing by hand, with an actual pen on actual paper. Since my handwriting resembles Foghorn Leghorn’s footprints, I have generally kept to the keyboard. I do, however, like to do mind maps with pen and paper. Sometimes I’ll block out a scene that way.

We’ve talked in the past about doing some of our writing by hand, with an actual pen on actual paper. Since my handwriting resembles Foghorn Leghorn’s footprints, I have generally kept to the keyboard. I do, however, like to do mind maps with pen and paper. Sometimes I’ll block out a scene that way. The first novel I ever wrote was about a boy who sneaks aboard a pirate ship. I was in third grade, in Mr. McMahon’s class at Serrania Avenue Elementary School, deep in the heart of the post-World War II paradise known as the San Fernando Valley.

The first novel I ever wrote was about a boy who sneaks aboard a pirate ship. I was in third grade, in Mr. McMahon’s class at Serrania Avenue Elementary School, deep in the heart of the post-World War II paradise known as the San Fernando Valley. In my

In my  I read a literary novel a few weeks ago, and it frustrated the heck out of me. There was a powerful story wanting to bust out, but I felt it was hemmed in by the author trying too hard to be, well, “literary.” There was an emphasis on style, some of it quite good. But the scenes didn’t grab me. The author wanted things implied rather than rendered dramatically on the page. That’s often a nice touch, but not for a whole book. There was too much description and narrative summary, and not enough on-the-page action and dialogue. Any momentum was stopped a few times with flashbacks (Chapter 2 being one of them; not a great place for a flashback ). The ending was ambiguous, and left me feeling nothing.

I read a literary novel a few weeks ago, and it frustrated the heck out of me. There was a powerful story wanting to bust out, but I felt it was hemmed in by the author trying too hard to be, well, “literary.” There was an emphasis on style, some of it quite good. But the scenes didn’t grab me. The author wanted things implied rather than rendered dramatically on the page. That’s often a nice touch, but not for a whole book. There was too much description and narrative summary, and not enough on-the-page action and dialogue. Any momentum was stopped a few times with flashbacks (Chapter 2 being one of them; not a great place for a flashback ). The ending was ambiguous, and left me feeling nothing. Once you wrap your head around the concept of the

Once you wrap your head around the concept of the