I’ve just returned from a ten day trip to Australia and, apart from a vestiges of jet lag, I’m also suffering from what I like to term ‘character withdrawal’. This has occurred because, despite my good intentions, I didn’t manage to get any writing done while I was away (my laptop remained firmly ensconced in my backpack, never to be opened). So now, as I hazily return to normality, I face a temporary silence – the voices of my characters have been mute for too long (and, I suspect, they’re a bit miffed about this…so they may actually be ignoring me). Oh, I’ve had the occasional glimpse of a scene, and a fragment of conversation maybe, but by and large I forgot my characters amidst the whirl of a family wedding and reunion. Now I’m going to have to listen hard to let these characters voices be heard once more.

So I was intrigued by a project conducted at the Edinburgh International Book Festival this year in which writers were asked about how they found their characters’ voices. More than 100 writers have so far participated in the project, responding in terms of how they experience their characters’ voices, and how this process had changed over their careers. A short summary of some of the initial findings of the study can be read here.

The most interesting finding for me (at least) was that many writers have different experiences when it comes to their primary and secondary characters. For primary characters/story protagonists writers reported that they tended to see the world through this character’s eyes, inhabiting that character’s interior life. They often found, at least early in their careers, difficulty in distinguishing their own ‘author’s voice’ from that of their main character. These writers felt as though the main character was formed through their own voice, often expressing what they, as the author, felt but could not express in real life (hmm…interesting…)

For secondary or minor characters, writers reported that they ‘saw’ them more visually rather than hearing (or being a conduit for, perhaps) that character’s voice. Many writers in the study also reported that as their writing careers progressed they found they were able to distance their own ‘author’s voice’ from the character’s voice and thus create primary characters that were no longer versions of themselves.

I’ve often wondered how other writers access their characters’ voices For me it tends to be a visual as well as an auditory experience – but it is true that often I cannot picture my main character as clearly as I can visualize the other characters, because I am, in many ways viewing my fictional world through the eyes of that main character.

So as I spend the next few days listening once more to my ‘inner voices’ and coming back to my writing, I wonder…how do you access your characters? Do you ‘hear’ their voices? Do you experience the process differently when it comes to your protagonist versus your secondary characters?

Author Archives: Joe Moore

How to Launch a Self-Published Book

James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I Screamed, I Cried, I Threw It Across the Room

Reader Friday: What’s Your Mood, Writer?

According to some studies, those who love to write may enjoy certain mental health benefits. One article states:

“No matter the quality of your prose, the act of writing itself leads to strong physical and mental health benefits, like long-term improvements in mood, stress levels and depressive symptoms. In a 2005 study on the emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing, researchers found that just 15 to 20 minutes of writing three to five times over the course of the four-month study was enough to make a difference.”

So how do you generally feel when you’re writing? After you’ve written?

I Am a Recovering Plot Pantser–There, I Said it

On Monday, guest Steven James had an excellent post on “Fiction Writing Keys for Non-Outliners.” I loved reading his thoughts on trusting the fluidity of the process and chasing after rabbit trails. I can relate to this as a writer. On Tues, our esteemed TKZ contributor, P. J. Parrish, expressed an argument in favor of more structure in her subtle post, “Sometimes You Gotta Suck It Up & Write The Darn Outline” in which she wrote about her love/hate relationship with outlining. These arguments got me thinking about my own process that has evolved over the years.

I started out as a total “pantser,” meaning I came up with a vague notion of characters or a story idea, then started writing to see where it would go. In general, I found this to be liberating and it unleashed my inner story teller, but I found (over time) that I ran out of gas about half way through and hit a wall. I always finished the project. I believe it’s important to finish what you start, if for no other reason than to learn how to get out of tight corners. There’s a true feeling of accomplishment to salvage a story that seemed to be headed for a dead end, and through practice, I learned what pitfalls to avoid. But as a writer under contract, I realized it would be a better use of my time to do some advance thinking on structure, rather than hoisting a shovel to shore up plot holes.

So I found a hybrid method that satisfied my “pantser” free spirit yet provided enough structure to serve as a guidepost – my lighthouse in the fog. I posted a more detailed presentation on TKZ HERE, but I wanted to highlight what this method does for me now.

NOTE: A word of caution on any detailed plotting method: A plot structure can become rigid and restrictive if it inhibits the author’s exploration into a new plot twist or character motivation. As Steven James said, some rabbit trails should be explored. For me, this is the fun of storytelling – to uncover a hidden gem of creativity.

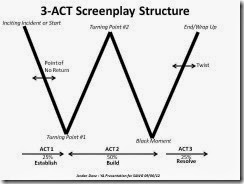

When I’m first developing an idea, I break it down into turning points (the 3-Act Screenplay Structure “W”) to get a general notion on structure. It helps me simplify the plotting/outline method into 5 turning points (the W). I can handle 5 things. I use this to write proposals and brainstorm with my crit group for their plots or mine. Rather than getting bogged down by character backstory or other details, I focus on “big ticket” plot movements to provide some substance.

The transition scenes between the turning points are still a mystery that can be explored, but in a synopsis, I can provide enough “meat to the bone” for an editor to get the idea and pair it up with a multi-chapter writing sample. Once I start writing the rest of the book, I can still explore rabbit holes and surprise character motivation twists to embellish the framework I’ve started with. I get my proposal out to my agent (with writing sample, synopsis and pitch) and keep working on current material. While I’m waiting to hear on a sale, I can set the material aside because I have a synopsis to act as a guidepost when I can get back to it. This method has also helped me plot out a whole series, to build onto the storylines (over a series of novels) and ramp up the stakes.

Focusing on turning points from the beginning (before I commit to the writing) has inspired me to spin major plot twists and “play with” the options I should consider. I can reach for complete 180 spins in a “what if” way. As an example of 180 degree turns, I’ve been inspired by the TV show CSI Vegas this season. Many of the episodes are so well written, they make a 180 turn at every commercial break and hit their marks with great twists. I’ve enjoyed this season so much that I record and go back over the plot by taking notes, to see how the writers developed the story. That’s what really good turning points can do for a book/TV show. They pull the reader/viewer into the story and challenge them to figure out where the plot is going. Who dunnit?

So I’m a reformed pantser who has found a way to keep a sense of free spirit, yet write with a framework when I’m ready to go. I feel more efficient, but I still have the flexibility to explore rabbit trails and trust my natural story telling ability.

I’d like to hear from you: How do you handle rabbit trails? Do you put all the work up front in the form of a detailed outline, or do you prefer a lighter touch to “discover” something as you write? Are you a hybrid plotter/outliner too?

Conference Overview #Ninc14

Having just come from the Novelists, Inc. (Ninc) conference, my brain is fried with all the important information I learned. You can see photos on my Facebook Page under the Ninc Album and read my blogs of each workshop on my personal blog site.

As an overview, here are some of the important points I took away from this event.

If you indie publish, offer your book at as many retailers as possible. These would include Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, Apple, Smashwords and Google Play. Google is growing.

Indie bookstores will survive the digital age, especially if they offer curating, personal service and community events.

Publishers may cry that they’re hurting but their profits are rising.

The global marketplace is not to be overlooked. There’s a huge market for English language books, plus the translation market is out there. Agents can still have a role with managing our subsidiary rights.

In the future, authors may sell directly to readers. Be prepared for new technologies and to take advantage of opportunities when they arise.

The real threat is the decline of recreational reading. There’s too much competition from video games, TV and movies, and other entertainment pursuits. We need to increase kids’ passion for reading.

Target your readers. Analyze your data. View your results and modify your business plan accordingly. Make sure you write the best book that you can and present the product in a professional manner.

Series sell better than standalones. Even if you aren’t writing a series, try to link your books with a common theme. Have cover art that ties them together.

Back material is important. Your e-book is a living document. Include links to your other titles and to your newsletter.

In the photo: Donna Andrews, Carole Nelson Douglas and Nancy J. Cohen

The rest is on my personal blog. Coming next there is BookBub, ACX, legalities for authors and more. Be sure to scroll down to see my previous posts.

For more information on Novelists, Inc., go Here.

Sometimes You Gotta Suck It UpAnd Write the Darn Outline

Before you read this, I’m going to suggest you back up one day and read Steven James’s Monday post, “Fiction Writing Keys for Non-Outliners.” It’s a really good argument against outlining and I agree with almost everything Steven says.

I hate to outline. To me, it’s on par with pap smears, getting your teeth cleaned, filing taxes, and watching the Raiders play the Jets. It’s tedious, painful and feels utterly pointless. It’s not fun. It’s a major buzz-kill.

But after reading Steven’s eloquent argument, I abandoned my post-in-progress and decided I needed to respond. Because I believe – hack, hack, hack! – that sometimes you just gotta suck it up and outline.

Did I mention I hate to outline?

First, some context. I have published, via the traditional New York house route, fifteen books. My first book was bought as a full manuscript and that is the norm. First-timers don’t usually get in the door without a finished book. But for my next book (in a two-book contract), I had give my editor a full outline. This was because I had not yet established my reputation and they needed assurance I wasn’t a one-trick pony. So I did the grunt work and wrote a detailed outline.

Did I mention I hate to outline?

This outline pattern stayed in place for my second two-book contract, but by book five, I went to contract on the strength of a five-paragraph concept. This was because by this point my editor knew I could write, make deadline, and sustain my series momentum. But when I switched to a new publisher, I had to go back to outlining because my new editor wanted a stand alone thriller. But for the four books that followed (which were back in my Louis Kincaid series), I was able to go back to contract via concepts.

I haven’t had to slog through the outline exercise for six years. Which brings us to the present. About a month ago, I submitted a detailed concept and 100 pages of my WIP to an editor at a traditional publisher. She loved it but she had to send it to the acquisitions committee, which okays every deal. (This is SOP for traditional publishing houses; everything is run up the flagpole to be saluted by editors, market types and bean counters). To do this, I had to give the editor…an outline.

Now, given my druthers, I am a confirmed pantser. My sister and I start with an idea, flesh out our main characters, then we plot-then-write in chunks of about four chapters at a time. But my new publisher wanted to know the major dramatic arcs of the story so Kelly and I spent two weeks not doing what we love – writing – but doing what we hate — brainstorming and sweating blood creating a plot map.

They bought the book.

Did I mention I hate outlining?

So I’ve swung both ways. Outlining is awful but it can be very useful if it gets you where you want to go. And every writer is different. Some of us thrive on structure; others crave chaos. There is no one path to the truth, grasshopper.

So who outlines? Let’s pull back the curtain and see…

John Grisham starts with 50-page outlines, with a paragraph or two about each chapter, setting out major events and plot points.

Michael Palmer spends four to five months outlining and goes to contract on outlines. His outlines are 40 to 60 single-spaced pages and his editor “clears” the outline before he writes one word. Sez Michael: “When I get down to the actual writing, I feel free to deviate from the outline, but out of courtesy, I will call and discuss any major deviations from what was agreed upon with my editor. There are those writers who can pen a novel and then do it over again if the story doesn’t work. With my busy schedule as a doctor and a daddy, I am not in that group. Reworking a detailed outline is possible for me. Rewriting an entire book would be disastrous.”

James Patterson writes a detailed outline and then hires someone to write the scenes, usually in 30 to 40 page chunks, which he reviews. Patterson describes it: “The outlines are very specific about what each scene is supposed to accomplish. I get pages from [the collaborator] every two weeks, and then I re-write them. That’s the way everything works. Sometimes I’ll just give notes. I’ve done as much as nine drafts of a book after the original comes in.”

Self-published eBook phenom Amanda Hocking (now in print with St. Martins) hand-writes her outlines before formatting them. “I’ll write usually about two or three outlines, so by the time I do write the book I’ve got the story completely mapped out in my head,” she says.

Joseph Finder describes writing without an outline like doing a high-wire act without a net, saying that his book Power Play, “took me several months longer than usual, simply because I wasted a lot of time on plot and on characters that I ended up cutting out.”

Robert Ludlum’s outlines routinely ran to 150 pages. I don’t know what he does now that he’s dead. I’d like to think he’s up there being a happy pantser.

Who doesn’t outline? Lee Child, for one. And Harlan Coben, who describes his process thusly: “I usually know the ending before I start. I know very little about what happens in between. It’s like driving from New Jersey to California. I may go Route 80, I may go via the Straits of Magellan or stopover in Tokyo but I’ll end up in California.”

That driving metaphor is a riff on E.L. Doctorow’s famous quote: “Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

I’ve written both mysteries and thrillers, some romance and even fat historical sagas. Some came easy; others fought me all the way. And while being a pantser is my default method, I have come to appreciate that outlining can be useful. Here’s why:

1. It helps you get rid of bad ideas. This is very important because we all have bad ideas and bad ideas are like the Devil — they often assume a pleasing shape. (Wow! What if I have the bad guy sneak some plutonium into a White House toilet, then the Senate minority leader comes out of the john with green skin and…) If you write your bad ideas down they won’t lurk in the shadows of your brain.

2. You might have to produce an outline to go to contract with a publisher. If you’re lucky enough to get a multi-book deal, outlining is often specified in contracts. Also, you get paid in lumps: part on signing, part on turning in the manuscript, part on publication. But sometimes, one of the lumps comes via outline. Also, your editor might have to approve the outline before you begin working on the book.

3. It can speed up the writing process. Just seeing a map on paper can often help you manage your writing time. If you have some idea of the journey, you can budget your time more efficiently. This is important as you get farther into your career and must produce a book or more a year.

4. If you write big complex plots, it can keep you on track. Ken Follett starts with an outline between 25-40 typed pages that details chapter-by-chapter events and includes bios of all characters. He shares this with his editors before he starts writing. He also rewrites his outlines!

I rewrite the outline – and this may happen several times. Typically there will be a first draft outline, a second draft outline and a final outline, so it would twice go through the process of being shown to a number of people. The whole process of coming up with idea, fleshing it out, doing the research, drafting the outline and rewriting the outline comes to about a year all told. There are quite often a couple of false starts within this. I may spend a month working on an idea before I realise that it isn’t going to work and abandon it. But after this whole process, I’m ready to write the first draft.

5. If you’re trying a new genre, it gives you confidence. I have a friend who, after a long and successful career writing a light amateur sleuth series, is making the switch to darker fare. She has always been an avid outliner but with this new project, she found even more extensive outlining gave her sure footing in her new territory.

6. It keeps you motivated and focused. While working on my new book, the hardest thing I had to deal with was my sense of being at sea. Because I was working without the security of a contract for the first time since starting out, I often felt myself drifting into a lot of “what ifs.” What if I can’t pull this story off? What if no one buys it? What if I’ve run out of good stuff and it’s time to hang up the creative cleats? But there was something about writing an outline — having to do the elbow grease of the mind and produce on deadline — that injected juice back into my story and resolve back to my spine. If nothing else, I finished the damn outline.

So, yes, outlining is a good thing. But…

Can I add my caveats? If you outline, please don’t let it put a strangle hold on you and your story. It is a guide, a suggested route, one way to go but never the only one. I love this quote from Donald Barthelme:

“Not-knowing is crucial to art, is what permits art to be made. Without the scanning process engendered by not-knowing, without the possibility of the mind moving in unanticipated directions, there would be no invention.”

So even if you do outline, leave room in your planning for serendipity and detours because, as Steven said so well in yesterday’s post, that is where your story is hiding out waiting for you.

Think of an outline as those colored lines they paint on the linoleum in hospitals to help you find your way. The red will get you to the cardiac unit, the yellow to the cafeteria, the black to the emergency room. But sometimes you just gotta follow the blue and go look at the babies.

Fiction Writing Keys for Non-Outliners

Note from Jodie: I’m pleased to welcome back bestselling author Steven James to TKZ, and am looking forward to presenting a workshop at Steven’s conference, Troubleshooting Your Novel, in Nashville on January 17.

Excerpted from Story Trumps Structure (Writer’s Digest, 2014) by Steven James

Twelve years ago I had an idea for a series of mysteries featuring a one-armed detective. I attended a seminar by a well-known novelist who taught us to carefully and meticulously outline our fiction and then stick to the outline as we crafted our stories. In some cases he would write a forty-page long, single-spaced outline and then spend his actual novel-writing time pretty much filling in the blanks.

Well, I didn’t get very far in the one-armed detective project. In fact, it went absolutely nowhere. The process of outlining seemed daunting, not a whole lot of fun, and a very artificial way to approach an art form—sort of like telling an artist to use a paint-by-numbers approach.

I realized that in my heart of hearts I’m a storyteller, not an outline-maker.

If that’s you, here are a couple of secrets I’ve picked up over the course of writing ten novels without any outlines.

I’ve found that when I tell people to stop outlining their stories, I get strange looks as if writing organically is against some sort of “rule” of writing.

Well, in that case, I invite you to the rebellion.

Discarding your outline and uncovering your story word by word might be the best thing you can do for your fiction, just as it was for me.

Here’s how to get started.

Trust the fluidity of the process.

I love Stephen King’s analogy in his book On Writing where he compares stories to fossils that we, as storytellers, are uncovering. To plot out a story is to decide beforehand what kind of dinosaur it is, how big it should be, and so on. As King writes, “Plot is, I think, the good writer’s last resort, and the dullard’s first choice.”

His analogy helps me to stop thinking of a story as something I create as much as it is something I uncover by asking the right questions.

When people outline their stories, they’ll inevitably come up with ideas for scenes that they think are important to the plot, but the transitions between these scenes (in terms of the character’s motivation to move to another place or take a specific action) will often be weak.

Why?

The impetus to move the story to the next plot point is so strong that it can end up overriding the believability of the character’s choice in that moment of the story.

Read that last sentence again. It’s a key one.

Stated another way, the author imposes the plot onto the clay without letting it be shaped by the essential forces of believability, causality, and context.

You might have had this experience: you’re reading a novel and it feels like there’s an agenda to the story that isn’t dictated by the narrative events. This is a typical problem for people who outline their stories. Instead, listen to the story, and respond to where it takes you.

You can often tell that an author outlined or “plotted out” her story when you read a book and find yourself thinking things like,

◦ “But I thought she was shy? Why would she act like that?”

◦ “I don’t get it. That doesn’t make sense. He would never say that.”

◦ “What?! I thought she was . . . ?”

◦ “Whatever happened to the . . . ? Couldn’t she use that right now?”

◦ “I don’t understand why they’re not . . . ”

This happens when an author stops asking, “What would naturally happen next?” and starts asking, “What do I need to have happen to move this story toward the climax?”

The first question grows from the story itself, the second places artificial pressure on the story to do something that might not be causally or believably connected to the story events that just happened.

As soon as your character doesn’t act in a believable way, it’ll cause readers to ask, “Why doesn’t she just . . . ?” And as soon as that happens, they’re no longer emotionally present in the story.

As you learn to feel out the direction of the story by constantly asking yourself what would naturally happen next, based on the narrative forces that shape all stories, you’ll find your characters acting in more believable and honest ways and your story will flow more smoothly, contingently, and coherently.

Here’s one of the biggest problems with starting by writing an outline: You’ll be tempted to stick to it. You’ll get to a certain place and stop digging, even though there might be an awful lot of interesting dinosaur left to uncover.

Follow rabbit trails.

Forget all that rubbish you’ve heard about staying on track and not following rabbit trails.

Yes, of course you should follow them. It’s inherent to the creative process. What you at first thought was just a rabbit trail leading nowhere in particular might take you to a breathtaking overlook that far eclipses everything you previously had in mind for your story.

If you’re going to come up with original stories, you’ll always brainstorm more scenes and write more words than you can use. This isn’t wasted effort; it’s part of the process. Every idea is a doorway to the next.

So, where to start? Put an intriguing character in a challenging situation and see how he responds. Sometimes he’ll surprise you in how he acts, or demand a bigger part in the story.

And sometimes a random character will appear out of nowhere and vie for a part in the story.

As J.R.R. Tolkien noted one time, “A new character has come on the scene (I am sure I did not invent him, I did not even want him, but there he came walking through the woods of Ithilien): Faramir, the brother of Boromir.”

For fans of The Lord of the Rings books, it’s a good thing Tolkien didn’t stick to some predetermined outline.

Where do ideas and characters like this come from? Tolkien’s contemporary and the author of The Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis, wrote, “I don’t believe anyone knows exactly how he ‘makes things up.’ Making up is a very mysterious thing. When you ‘have an idea’ could you tell anyone exactly how you thought of it?”

While the exact genesis of ideas will always be, as Lewis points out, somewhat mysterious and impossible to pin down, we can tip the scales in our favor when we remember, that they often come from the questions, attentiveness, observance and responsiveness of the artist, the author, the poet, or the musician.

Allow your characters the opportunity to flex and adapt and grow, revealing to you their quirks and inconsistencies, even as you push them to the limit to see how they respond. Then let the story shape them even while they shape the direction of the story.

The key is responding to the story as it unfolds, being honest, keeping it believable, letting the characters act and develop naturally, and following where the trail of the story takes you. Give yourself the freedom to explore the terrain of your tale.

Without serendipitous discoveries, your story runs the risk of feeling artificial and prepackaged.

+++++++++++++++++++++

Steven James is the bestselling, critically acclaimed author of ten novels. When he’s not writing, trail running or watching science fiction movies, he’s teaching storytelling around the world. http://www.storytrumpsstructure.com/

Writing What You Love and Earning What You’re Worth

Stress vs. Fiction