What’s an early memory of failure or defeat? How did you handle it? What did you learn, and how does it apply to your writing life?

Monthly Archives: May 2014

Discovering Story

Part of the creative process is Discovery. I’m in this phase now, which is when the beginning of a plot swirls in my head. I have a title for my next mystery, so I have to work the murder around it. Thus I’ve made an appointment for a facial. I know, research can be tough but someone’s got to do it. And my Bad Hair Day series is centered around a beauty salon.

Often I’ll start the plotting process with the victim. As shown in my book, Writing the Cozy Mystery, I draw a circle in the center of a paper and put the victim’s name inside. Around that go spokes like on a wheel for each of the suspects. Then I connect the spokes together so it becomes more like a spider’s web, where the suspects relate to each other in some manner.

For now, I know my victim’s basic identity. Her job is what gets her into trouble, and so the suspects develop from among her business associates. Who might want her dead and why leads me to motives. At this point, preliminary research is in order. I need to look up the world surrounding her business and learn more about it.

But that’s not all. I am driven to acquire new knowledge about a subject for each book. What will it be for this one? What issue interests me, or what news article have I filed among my clippings that I might want to pursue? This factor is what propels me forward and underlies the plot. It hasn’t come to me yet for this story.

My victim is co-sponsor of a beauty pageant. I search online and fine headlines like “Top 10 Beauty Pageant Scandals.” Bingo! Before looking these over, I realize I have a problem. Most pageants likely take place over a weekend. How can I get this group of people to stay in the Fort Lauderdale area for a week or two so my hairdresser sleuth, hired to do the contestants’ hairstyles, can ferret out clues?

I’ll deal with that problem later. Meanwhile, I look at the scandals online regarding beauty shows, and nothing strikes me in terms of issues I’d want to pursue. The problems encountered don’t seem worthy of murder. And do I really want to write a whodunit variation of Miss Congeniality?

Hey, what if I do a fashion show instead of a beauty pageant? My last Bad Hair Day mystery, Peril by Ponytail, takes place in October. I could set the new story in December. I’ve done Thanksgiving in Dead Roots but never Hanukah or Christmas. So how about a charity holiday ball with a fashion show? Using a local designer would keep the action in town, and I’ve already done the preliminary research by going backstage at a designer showcase. This will give me the personal angle of Marla and Dalton dealing with the holidays while also picking a charity whose cause I can support. If Marla has a connection to the charitable organization through her friends or relatives, this would give her an added incentive to get involved in solving the murder.

I like this idea. It’s starting to get me excited, whether or not it pans out. At least, it’s a start in the right direction.

So what advice do I have for you based on this experience? When you begin to think about the next story, let ideas flow through your brain. Pick the one that excites you and do your preliminary research. If you find some meaty material, go with it. If not, let the idea float away but keep the story in your mind. Your subconscious will present the next idea. Or thumb through your files and see if one of your clippings or news pieces stimulates a train of thought.

Do you start story development with an issue, a character, or a setting?

Stealing From Other Writers

By P.J. Parrish

When I write, I don’t read. Because I know, from experience, what happens when I do. I steal.

Now, don’t get me wrong. All writers steal. At least, the smart ones do. Because this is partly how you learn to write a novel, by reading other novels, figuring out how the person structured the story, analyzing how the characters were layered, how the motivations were laid out, how the words were put together to elicit an emotional response. We learn by digesting the craftsmanship of others.

Here’s the thing though: You have to steal in the right frame of mind. And for me at least, that is NOT when I am working on my own book. If I see a way of structuring a scene or chapter that is clever, I will try to replicate it in my own book. If I read a passage that sings, I will try to mimic it even if it’s not my style. When I am writing, I am in this weird fugue state and my brain is very porous and open. The temptation to take things that really don’t belong to me is too great.

But something changes once I am done writing my own book. I binge read for pleasure. Freed from my own insecurities and writer ego, I hear other writers more clearly. And when that happens, I learn more about writing in general and the lessons sort of sit in my brain, baking and bubbling, until I need them.

So, yes, I steal from other writers. Here are some of the things I have taken and the people I took them from:

Every sentence must do one of two things: reveal character or advance the action. I stole this from Kurt Vonnegut. About ten years ago, I was struggling mightily to write my first short story. I went back and read Cheever, Hemingway, Saki and O Henry. I discovered John D. MacDonald’s The Good Old Stuff. But it wasn’t until I got to Vonnegut’s Bagombo Snuff Box that I hit pay dirt. In the preface, Vonnegut laid out his eight rules for writing. (Click here to read them all.) His idea that every sentence must reveal character or advance plot was a light bulb moment for me. It now informs everything I write. And when I teach, I try to impress on writers that every scene, every chapter, must work hard in service to the twin poles of character and plot.

Kill Your Darlings. Nope, I didn’t get this one from Faulkner. I stole this from E.B. White. And by “darlings” I mean good characters. Charlotte’s Web is my favorite book, maybe the one that most influenced me as a writer. It has many great lessons but the most enduring is that a writer can – must – be brave enough to kill a good character. I’ve written about this before, so click here if you want to read more.

Fall in love with the sound of language. Stole this one from Truman Capote after reading Music for Chameleons. This is a miscellany of stories and essays published in 1980 after a 14-year drought following Capote’s brilliant In Cold Blood. It contains passages of exquisite beauty and it taught me, when I was just starting to write, to pay attention to what words sounded like. Like those chameleons in the lead story, I was mesmerized by the music, and have spent all the years since trying to make my own. (In his preface, Capote writes: “When God hands you a gift, he also hands you a whip for self-flagellation.” Ha!)

Don’t be afraid! This one I got from Mike Connelly’s The Poet. For most of our Louis Kincaid series, we have stayed mainly with a third-person intimate POV because we think filtering the story through our hero’s consciousness enhances the reader’s bond with him. But when we started our first stand alone thriller, The Killing Song, we realized our protag and villain were equally important. We needed something special to drive home their dichotomy of good and evil, so we decided to copy Connelly’s The Poet and mix first and third POVs. Our first chapter was written in first-person from the killer’s POV and the second chapter switched to third-person from the hero’s POV. But it wasn’t working. And we couldn’t figure out why. I ran into Mike at Bouchercon and told him I stole his idea. He smiled, shook his head and said, “But give the first-person to your hero. It’s his story.” We took his advice and the story took off. But I wouldn’t have had the guts to try without reading The Poet.

There have been other lessons learned from my life of crime. From Stephen King, who has tried everything from horror to westerns, from eBooks to novellas, I learned not to let expectations box me into one genre or style. This has given me the courage to use an unreliable narrator in my WIP. As E.B. White said, “Sometimes a writer, like an acrobat, must try a trick that is too much for him.”

From Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, I stole the idea that a protagonist can be deeply flawed. From Jane Austen’s Emma I learned to pay attention to secondary characters because they might hold the key to the story (In the end, George Knightley won Emma’s heart). From Pete Dexter’s Paris Trout, I got the revelation that all good crime stories are not about the crime but rather its rippling effect on the people and the town. And last but not least, From Anne Lamott, I learned that my quest for perfectionism is death. She wrote in Bird by Bird: “The only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts.” Which might be the best advice for writers I have ever heard.

Who do you steal from? And what treasure did you get?

How to save a bundle on editing costs – without sacrificing quality

by Jodie Renner, freelance fiction editor & craft-of-writing author

by Jodie Renner, freelance fiction editor & craft-of-writing author

If you’re relatively new at writing fiction for publication, whether you plan to publish your novel yourself or query agents, it’s a good idea (essential, really) to get your manuscript edited by a respected freelance fiction editor, preferably one who reads and edits your genre. Can’t afford it, you say? I say you can’t afford not to, but below you’ll find lots of advice for significantly reducing your editing costs, with additional links at the end to concrete tips for approaching the revision process and for reducing your word count without losing any of the good stuff.

Editing fees vary hugely, depending on the length and quality of the manuscript, and how much work is needed to take it from “so-so” or “pretty good” to a real page-turner that sells and garners great reviews. Before approaching an editor, hone your skills and make sure your story is as tight and compelling as you can make it – and that it’s under 100,000 words long. 70-90K is generally preferred for today’s fiction.

Don’t be in a hurry to publish your book before it’s ready.

If you rush to publish an early draft, you could do your reputation as a writer a lot of damage. Once the book is out there and getting negative reviews, the bad publicity could sink your career before it has had a chance to take off. It’s important to open your mind to the very real possibility probability that your story could use clarification, revising, and amping up on several levels, areas that haven’t occurred to you because you’re too close to the story or are simply unaware of key techniques that bring fiction to life.

First, write freely, then step back, hone your skills, and evaluate.

First, get your ideas down as quickly as you can, with no editing – write with wild abandon and let your muse flow freely. But once you’ve gotten your story down, or as far as your initial surge of creativity will take you for now, it’s a good time to put it aside for a week or three and bone up on some current, well-respected craft advice, with your story in the back of your mind. Then you can re-attack your novel with knowledge and inspiration, and address any possible issues you weren’t aware of that could be considered amateurish, confusing, heavy-handed, or boring to today’s sophisticated, savvy readers.

Now’s the time to read a few books by the writing “gurus” (here’s an excellent list), and some of the great craft-of-writing posts by The Kill Zone’s contributors in the TKZ Library (in the sidebar on the right), and maybe join a critique group (in-person or online) and/or attend some writing workshops.

Now’s the time to read a few books by the writing “gurus” (here’s an excellent list), and some of the great craft-of-writing posts by The Kill Zone’s contributors in the TKZ Library (in the sidebar on the right), and maybe join a critique group (in-person or online) and/or attend some writing workshops.

Then, notes in hand, roll up your sleeves and start revising, based on what you’ve learned. If you then send your improved story, rather than your first or second draft, to a freelance editor, they will be able to concentrate on more advanced fine-tuning instead of just flagging basic weaknesses and issues, and will take your manuscript up several more levels. Not only that, you’ll “get” the editor’s suggestions, so the whole process will go a lot smoother and be more enjoyable and beneficial.

A great book to start with is my short, sweet, to-the-point editor’s guide to writing compelling stories, Fire up Your Fiction. And for more on point of view, avoiding author intrusions, and showing instead of telling, peruse Captivate Your Readers. And if you’re writing a thriller or other fast-paced story, check out my Writing a Killer Thriller for more great tips. All three are available in print or e-book, which you can also read on your computer, tablet, or smartphone.

And when it comes time to find a freelance editor, don’t shop for the cheapest one and insist that your manuscript only needs a quick final proofread or light edit. That approach will result in a cursory, superficial, even substandard job, like painting a house that’s falling over and needs rebuilding, and will actually end up costing you more money in the long run. Why?

Because you could well be unaware of how many structural, content, and stylistic weaknesses your story may contain, which should be addressed and fixed before the final copyedit stage. Paying for a basic copyedit and proofread on a long, weak manuscript, only to find out later it needs a major overhaul, which will then require rewriting and another copyedit, is short-sighted — and money down the drain.

Say, for example, your novel is a rambling 130,000 words long. It’s very likely you need to learn to focus your story, cut down on descriptions and explanations, eliminate or combine some characters, maybe delete a sub-plot or two, plug some plot holes, fix point-of-view issues, and turn those long, meandering sentences and paragraphs into lean, mean, to-the-point writing. Not only will this make your story much stronger and more captivating, but it will save you a bundle on editing costs, since freelance editors charge by the word, the page, or the hour, and editing your 80,000-word, tighter, self-edited and revised book will cost you a whole lot less than asking them to slug through 130,000 words written in rambling, convoluted sentences.

Your story may even need a structural or developmental edit.

If you’re at the stage where you know it’s not great but you’re too close to your story to pinpoint the weaknesses, perhaps you should hire a developmental editor to stand back and take a look at the big picture for you and give you a professional assessment of your manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Or if you can’t afford a developmental editor, try a critique group or beta readers – smart acquaintances who read a lot in your genre – to give you some advice on your story line and characters, and flag any spots where the story lags or is confusing or illogical.

Enlist help to ferret out inconsistencies and inaccuracies.

You don’t want to lose reader trust and invite bad reviews by being careless about facts and time sequences, etc., either. Find an astute friend or two with an inquiring mind and an eye for detail and ask them to read your story purely for logistics. Do all the details make sense? How about the time sequences? Character motivations? Accuracy of information? For technical info, maybe try to find an expert or two in the field, and rather than asking them to plow through your whole novel, just send them the sections that are relevant to their area of expertise.

It’s even possible that you’ve based your whole story premise on something that doesn’t actually make sense or is just too far-fetched, and the sooner you find that out the better!

Read it aloud.

Read your whole story out loud to check for a natural, easy flow of ideas, in the characters’ vernacular and voice, and suit the tone, mood, and situation. This should also help you cut down on wordiness, which is your enemy, as it could put your readers to sleep.

The more you’re aware and the more advance work you do, the less you’ll pay for editing.

So, to save money and increase your sales and royalties, after writing your first draft, it’s critical to hone your skills and revise your manuscript before sending it out. Also, be sure to find an editor who specializes in fiction and edits your genre, and get them to send you a sample edit of at least four pages. (See my article, “Looking for an editor? Check them out very carefully!”)

And don’t seek out the cheapest editor you can find, as they may be just starting out and unaware of important fiction-writing issues that should be addressed, like point of view and showing instead of telling, etc. And whatever you do, don’t tie the editor’s hands by insisting your manuscript only needs a light edit, because that’s cheaper. You could well end up paying for that “cheap” light edit on an overlong, weak manuscript, then discovering that the story has big issues that need to be addressed and requires major revisions, including slashing and rewriting. Then you’ll have to pay for another complete edit of the new version! $$ multiplied!

Check out these other articles by Jodie for lots of concrete tips on revising and tightening your novel (Click on the titles below):

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.

Why Marketing Is Like Motherhood

How To Pick A Title For Your Novel

Reader Friday: Other Things That Matter

Writers think about writing all the time. Self-publishing writers have to add all the business aspects of publishing, and everybody is on social media. It’s easy to get so focused on writing stuff that other things in life get fuzzy.

So today, take off your writing hat for a moment and talk about something else that matters to you.

Five Key Ways to Create a Character’s Distinct Voice

Jordan Dane

@JordanDane

Inspired by Joe Moore’s excellent post yesterday on Narrative Voice, I thought about my process for making characters distinct in the worlds I build in a novel. We are all influenced by where we grew up or where we live now, our race, social class, jobs, friends, religious beliefs, and other factors. Any character an author creates is no different. It’s not enough to picture their outward appearance. Give them a background and sphere of influence. Sometimes it helps for me to hear their voices in my head. (Yes, that’s allowed without taking medication. Special dispensation for authors.)

I recently binged on Sherlock (a la Benedict Cumberbatch) and Sleepy Hollow (British star Tom Mison’s reinvented Icabod Crane). I loved the notion of Sherlock’s brilliant mind leaps and I also loved the idea of a more stilted proper speech of an educated scholarly man similar to the Oxford professor of Icabod Crane, but I wanted my character to be American with a brash punch to him when he wanted to make a point. Those rare moments of punch give him a sense of gravitas and unexpected depth of personality. Being familiar with these TV characters, it became a fun challenge to meld their distinct voices and mannerisms into my American FBI profiler haunted by visions of crime scenes when he sleeps.

It’s amazing fun when you can hear the character voice in your head and write with a good pace, without filtering the words you type on the page. I call this “free association” where you channel the voice of your character without having to think about it. Over the years I’ve gotten better at this, which also comes with a cautionary warning born of experience. Often if you THINK in free association without filter, you will SPEAK that way too. Not always good in a social setting. #FilteringSavesLives

Five Key Ways to Give Your Character a Distinct Voice

1.) Word Choices:

- What is your character’s vocabulary?

- How educated is he/she?

- How much does race/culture play into his/her narrative?

- Are there regional influences on his/her speech? (I feel most comfortable writing in Midwest, TX, OK, and Alaska, places I’ve lived and worked.)

- Is slang or pop culture references a part of his/her speech patterns? (A secondary character can use slang as a way to distinguish that character’s voice from the protagonist. Fewer tag lines necessary.)

- How old is your character? (Don’t force a more youthful influence if you aren’t comfortable, but be aware of generation gaps.)

- Is your character from another country? (Word choices and even spellings can indicate where a character is from. I wouldn’t take any short cuts here. If your character is British, but YOU as the writer aren’t as familiar with nuances of a particular region in the UK, get help from a native speaker or build a backstory where your character has other influences that will temper their voice into more of a melting pot.)

- What gender is your character? (Gender can play a big part in making narrative distinctive. Avoid the cliché, but men and women are fun to contrast, no matter what your vision is for unique individuals.)

2.) Confidence Level:

- If your character is an assertive cop or from a military background, he or she would expressive themselves in a more direct and decisive fashion.

- How forceful or passive is your character? (A deliberate use of the passive voice can be an indicator of a submissive character. Use of “Uh” or “Um” can indicate hesitation and lack of self-confidence.)

- Does he or she take charge and have a no nonsense approach to dealing with conflict or do they only react and let others take over? (Even their clothes choices can indicate how confident they are.)

3.) Quirks/Mannerisms:

- Does your character have distinctive habits or mannerisms? (Sometimes a facial tic can be fun to exploit at key times.)

- Does your character have a unique hobby or interest that affects how they speak? (Someone into sailing could infuse nautical words, for example.)

- What humor do they have, if any? (Characters can have humor play out cynically in their internal monologue, yet their dialogue lines don’t reflect humor at all. This can be great for comic relief. Also characters can have distinctive sense of humor from very dry to crass bathroom humor.)

4.) Internal/External Voice:

- Your character might have a day job, but at night they come home to a family with small children or a demanding pet. How does their internal voice change when they let their guard down? Do their internal thoughts show a more tender vulnerability? This duality can bring depth and complexity to your character.

5.) Metaphors/Similes/Comparisons:

- I love imagery, but let’s face it, some characters will never think in terms of elaborate metaphors. It would not make sense to force it. In the case of my educated professor type, for example, his narrative could be infused with imagery/metaphors or perhaps literary influences because that’s how his mind works. He sees reality of the world around him yet he longs for the fictional world of his favorite book. If my character is a street kid without much education, he might be more influenced by rap music lyrics or the daily hustle on the street where he fast talks to survive everyday. No matter who your character is, they would have their own frame of reference for making comparisons.

FOR GRINS & GIGGLES: I took a little champion New York Times Online Test of 25 questions that analyzed how I spoke to determine where I live. (Best suited for residents of the U.S.) The test came back with a result that I lived in Rockford Illinois, New Orleans, and Rochester NY. Totally wrong since I live and grew up in Texas, but my mother was a Yankee and I’ve lived all over the country, so apparently that has also influenced me.) Take the test and see what your results are. Did they get it right? Let us know.

For TKZ Discussion:

How do you infuse a unique voice to your character? What are your key influences? If you’ve written characters outside your comfort zone, what tricks can you share about how to make that work?

Narrative Voice

A few weeks ago, I blogged about POV shifting and what’s called “head hopping”. To carry on with the topic of POV, I want to dig into a common topic discussed at workshops and critique group: narrative voice. Narrative voice determines how the narrator tells a story. Often it’s the voice of a character, less often, an unseen voice. The narrative voice is what provides background information, insight, or describes the actions and reactions taking place in a scene. Before a writer sets out to tell a story, she must choose which narrative voice to use. Here is a basic list and comparison of the different choices and why one might be more adventitious that the other in a particular project.

Although dialogue plays a critical role in fiction, having a story told completely with dialogue would be out of the ordinary if not downright creepy. No matter how many characters there are in a typical novel, there’s one that’s always there but is rarely thought of by the reader—the narrator. Like the referee at a football game, the narrator’s job is to impart necessary information and, in general, keep order. Someone has to tell us about mundane stuff like the time of day, the weather, the setting, physical descriptions, and the other things that the characters either don’t have time to tell us about or don’t know.

And just like the characters, the narrator—the author—has a voice or persona. Some authors like to be a part of the story and make themselves known through a distinct personality and attitude. Others prefer to remain distant and aloof, or completely transparent. One of the main things that determine the narrator’s voice is point of view.

Most stories are written in either first- or third-person. If it’s first-person, it’s usually subjective. Subjective POV tells the reader all the intimate details of the protagonist—her thoughts, emotions, and reactions to what’s going on around her. There’s also first-person objective. This story telling technique tells us about what everyone did and said, but without any personal commentary, mainly because the narrator doesn’t know the thoughts of the other characters, only their actions and reactions. First-person narration is all about “I”. I read the book. I took a walk. I fell in love.

In between first- and third-person is a rare POV called second-person. You don’t see this technique used much, and when you do, it’s about as pleasant as standing in line for hours at the DMV. Second-person narration is all about “you”. You read the book. You took a walk. You fell in love.

Next is third-person. There are a couple of third-person types starting with limited. As the term implies, this is a story technique told from a limited POV. It usually involves internal thoughts and feelings, and is the most popular narration style in commercial fiction.

We can also use third-person objective. The narrator tells the story with no emotional involvement or opinion. This is the transparent technique mentioned earlier. The interesting advantage of third-person objective is that the reader tends to inject more of his or her emotions into the story since the narrator does not.

Then there’s third-person omniscient. With this POV, the narrator pulls the camera back to see the bigger picture. He is god-like in his knowledge of everyone and everything. This POV works well when dealing with sweeping epic adventures that might span numerous generations or time periods. Unlike first-person subjective, which is up close and intimate, third-person omniscient is distant, impersonal, and sometimes cold. The reader has to use his imagination more when it comes to emotions because there’s no one to help him along. Third-person narration is all about “he, she and they”. He read the book. She took a walk. They fell in love.

The other key element in determining narration and voice is verb tense. Most stories use the past tense. This is what most readers are comfortable with. The opposite of this would be the incredibly annoying and almost unreadable second-person present tense. If you’re interested in experimental, artsy writing and want to use this technique, make sure you’re independently wealthy and have no interest in actually selling copies of your book.

So who does the talking in your books? Does your narrator’s voice seem warm and fuzzy, cleaver and funny, or cold and distant? Do you stick with the norm of third-person past tense or do you like to venture into uncharted territory? And what type of narration do you enjoy reading?

——————————-

Coming soon:THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore

Coming soon:THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore

“THE SHIELD rocks on all cylinders.” – James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of THE EYE OF GOD.

Forty years later, a first high school reunion

I went to my 40th high school reunion last weekend, and I’m so glad I did. I had a small and treasured group of friends in school, but over the years my peripatetic lifestyle had caused me to lose touch with them. When it dawned on me that our graduation digits were turning the Big 4-0, I decided to step on a plane and head from Los Angeles to Boston.

As anyone who has attended a major reunion for the first time already knows, it felt strange at first to suddenly reconnect with people I hadn’t seen in decades. I remembered us all as kids, but now we were all older adults. I had to quickly reconcile my memories of the past with the mature present. The gangly, shy boy I’d known is now the dapper periodontist; the former tom boy and gal pal is now the accomplished television professional.

|

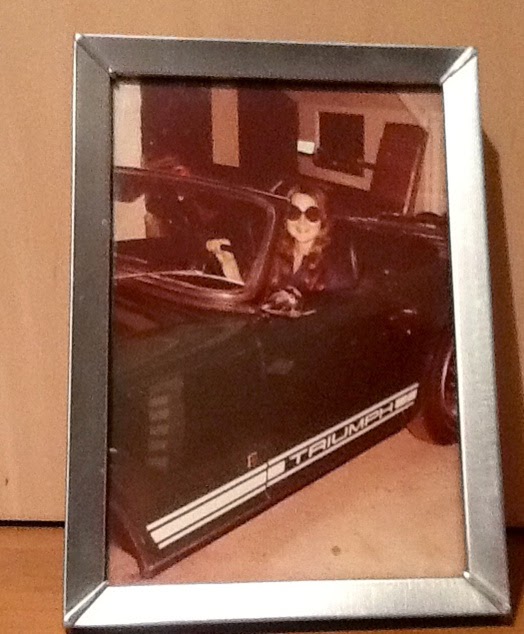

| Getting my first wheels, circa ’73 |

I think we attend reunions to reconnect, not just with others, but with a sense of ourselves from an earlier time. As I sat at the reunion table, I tried to remember what I was like in high school, what my ambitions had been back then. I remember that I loved English class, especially creative writing assignments. But I didn’t connect my vague enjoyment of writing with any notion of a future career. I come from a family of scientists and academicians. Our clan regards writing as a tool, not an aspiration. I thought the ambition of becoming a writer was only meant for the literati and artistes.

I wish I’d known when I was young that “real” people can become writers. It would have helped me get started earlier. So, here’s my advice to all the high school English teachers out there: invite a local novelist to speak about writing to your class. You might just be giving that quiet girl in the third row a vision of her future.

Question for you all: have you ever braved a high school reunion before? How did it go?

Update: I just added a picture of me “back in the day”–thanks to Jordan for the suggestion!