By Joe Moore

@JoeMoore_writer

Welcome back to TKZ after our winder break. I hope all of you had a wonderful time off with your families and friends. So, now it’s time to get back to work.

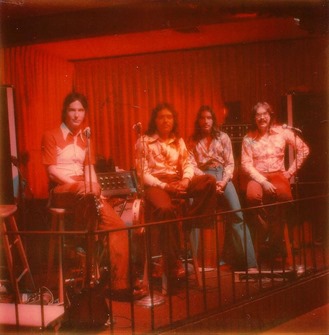

When I graduated from college, I was making a living doing two jobs: a night gig playing in a rock band (that’s me on the right), and a day job working in a music store. On the marquee in front of the store, was the message: Every Professional Was First An  Amateur. Since I was making decent dollars rocking out eight days a week, I considered myself and my band mates professionals. But that statement out on the store marquee stuck with me. Many decades later, when I took to writing fiction, that saying haunted me. Especially as I piled up an impressive stack of rejection letters. I used to brag that I had been rejected by some of the biggest names in the business. When I finally got an agent and had a novel published, I looked back at the trail of dead manuscripts left in my wake and realizes how true it was.

Amateur. Since I was making decent dollars rocking out eight days a week, I considered myself and my band mates professionals. But that statement out on the store marquee stuck with me. Many decades later, when I took to writing fiction, that saying haunted me. Especially as I piled up an impressive stack of rejection letters. I used to brag that I had been rejected by some of the biggest names in the business. When I finally got an agent and had a novel published, I looked back at the trail of dead manuscripts left in my wake and realizes how true it was.

I believed that my first manuscript was so great, it was supposed to make me into the next Clive Cussler. As you can guess, things didn’t turn out as planned. The closest I ever got to Cussler’s success was having dinner with him while I served as ITW co-president.

I’ve had the opportunity to mentor new writers through the MWA mentoring program and held countless writing workshops. What I’ve noticed is that all beginning writers commit the same sins. And what I wind up telling them is that there’s good news and bad. The good news is, they’ve accomplished something that only a small percentage of the population ever will. Most just dream about it. Few really sit down and write a book.

Now for the bad news: Their first book is not publishable. The response usually goes like this.

What? Joe, are you crazy? Everyone says my book is great. My mom loves it. My neighbors and the girl that cuts my hair said it was a potential bestseller—as good as King and Patterson. I’ve even been told by my uncle who watches lots of movies that it would make a blockbuster feature film. JJ Abrams would snap it up in a heartbeat. So how can you say that about a book when you’ve only read a few pages?

The reason I can say it with confidence is that I’ve found first novels to all be the same—not in subject matter of course, but in common, predictable flaws. And if by some miraculous stroke of luck the literary gods smiled down and their first book is publishable as written, then I would suggest they run to the nearest convenience store and buy a lottery ticket. There’s a good chance they’re on a roll.

I’ve made a list of the most common flaws of first novels. Keep in mind that having one or even a couple of these present in your book will not render the manuscript DOA. But I guarantee you’ll find just about all of them in the typical first attempt at writing a novel. Here they are in no particular order of importance.

You often use adverbs at the end of dialog tags to “tell” the reader what emotion the character feels. Example: “I’m mad as hell,” he said angrily. “I love you,” she said adoringly.

You rarely utilize any of the 5 senses to draw the reader into the scene.

You resolve conflict with coincidence or luck.

Your manuscript is filled with back-stories that don’t relate to the plot or develop the characters.

You head-hop within a scene between multiple POVs.

You tell the story rather than show it.

You have a “unique” approach to the use of the English language, and the mechanics and structure of writing in English. Note: I mean this in a bad way.

Each page is filled with an abundance of adjectives that if deleted would not change anything other than make the writing cleaner.

You recently discovered the exclamation point and want your readers to share in your excitement.

You love ellipsis . . .

You have a pet word or phrase that you feel compelled to repeat often in hopes that it will become a favorite of your reader.

You beat your readers over the head with repeated facts just in case they didn’t get it the first dozen times.

You often rely on the lazy technique of imparting information to the reader by having a character tell another something they already know.

Your text is riddled with more clichés than you could shake a stick at.

You use profanity for no other reason than shock.

Your dialog sounds as natural as a first grade primer.

Your characters continually use the name of the person to whom they’re speaking.

You overuse flashbacks and/or start the story with one.

Act II sags like a piece of pulled taffy.

Your story wanders.

Your story starts in the wrong place.

You’re not sure how to create suspense, so you commit “author intrusion” even though you have no idea what the term means.

You confuse the reader.

Your facts are incorrect. Example: The assassin attached the silencer to the revolver so no one would hear the shots.

You slip from past tense to present in narration.

You describe every movement, every second, every detail and every breath of your characters actions for no apparent reason.

You don’t know when to end a scene.

Your plot is a rehash of The Perils of Pauline—your protagonist jumps from one terrible situation to the next equally terrible situation with no dynamics or variation in terribleness.

You either have no subplots or enough for 10 books.

All your characters sound the same when they speak.

Your characters have no flaws.

You rely on stereotypes. The men are all handsome with chiseled faces and athletic bodies. The women are beautiful fashion models. And the bad guys are ugly, disgusting monsters. Note: This is OK if your antagonist is actually an ugly, disgusting monster.

Your story is melodramatic.

Your target audience doesn’t exist.

You manuscript is infested with misspellings, the wrong use of words, grammatical errors, and missing or incorrect punctuation.

You believe that placing the word “very” or “really” in front of an adjective increases the descriptive value of the adjective.

And the one that I see most often: You find it impossible to tell someone what your book is about without rambling on for 10 minutes.

Everyone’s first book contains just about all of the above. Mine did, and I’ll bet yours did, too. But that’s OK. That’s part of the learning process on the road to becoming a published novelist. Every professional was first an amateur. Every bestselling author wrote a first novel that should never see the light of day. Chances are it was just as full of these flaws as yours and mine.

The secret to this whole novel-writing thing is to keep writing. Few first novels are accepted by an agent much less bought by a publisher. Published first novels are the exception to the rule. For everyone else, you’ve got to write that second book. And the third. And the fourth. That’s how you refine the craft. And with each manuscript, you learn to use less clichés, eliminate “very” from your vocabulary, delete needless “ly” words, make your characters more human, find your writer’s voice, and all the other thousands of parts to crafting a well-written story.

So, Zoners, did I miss any beginner failings?