We now take our annual two-week hiatus. From all of us to all of you, thanks for another great year on TKZ! See you back here on January 1, 2019.

Stay warm … and keep writing!

Christmas is coming, the goose is getting fat.

Please put a penny in the old man’s hat.

And if you are promoting, I’m sure it’s no offense

If you sell the man some Kindle books for 99¢.

Yes, ’tis the season for self-indulgent poetry, and a couple of announcements.

The first is that my fourth Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Fight, is set to release on January 7th. It’s available for preorder for the special launch price of $2.99. In February it will go up to $3.99. Naturally I would appreciate it if you would hop over to Amazon and reserve your copy. On launch day you’ll get it automatically delivered to your Kindle.

The first is that my fourth Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Fight, is set to release on January 7th. It’s available for preorder for the special launch price of $2.99. In February it will go up to $3.99. Naturally I would appreciate it if you would hop over to Amazon and reserve your copy. On launch day you’ll get it automatically delivered to your Kindle.

(You international readers can find it in your Amazon store by pasting this ASIN number into the search box: B07L9DLGVF)

Welcome back!

Romeo’s Fight, like all the Romeo thrillers, can be read on its own. But if you’re one of those who likes to read a series in order, I’ve got some good news: for the next two weeks the first three Romeos are all priced at 99¢. Now’s the time to hop on this International Thriller Writers Award winning train. The order is:

1. Romeo’s Rules

2. Romeo’s Way

3. Romeo’s Hammer

Romeo’s Fight opens this way:

“So you’re Mike Romeo,” the guy said. “You don’t look so tough.”

I was sitting poolside at the home of Mr. Zane Donahue, drinking a Corona, and wearing a Hawaiian shirt, shorts, flip-flops and sunglasses. I was the perfect embodiment of L.A. mellow, trying to enjoy a pleasant afternoon. Now this shirtless, tatted-up billboard was planted in front of me, clenching and unclenching his fists.

“I’m really quite personable once you get to know me,” I said.

“I don’t think you’re tough,” he said.

“I can recite Emily Dickinson,” I said. “Can you?”

He squinted. Or maybe that’s how his eyes were naturally. His reddish hair was frizzy. With a little care and coloring, it would have made a nice clown ’do. He had a flat nose, one that had been beaten on pretty good somewhere. In a boxing ring, the cage, or prison.

“Who?” he said.

“You don’t know Emily Dickinson?”

Blank stare.

“Then you’re not so tough yourself,” I said.

I took a sip of my brew and focused on the devil tat above his left nipple. Underneath were the words DIE SCUM.

So let’s talk a bit about marketing, specifically two items: the browsing sequence and the building of buzz.

We start with the old-school bookstore browser. She walks into Barnes & Noble, perhaps with a title in mind, but takes a moment to look at the New Release table. What is the first thing that attracts her attention? The cover. If the cover has the name of an author she’s read before, and likes, that book gets picked up first. Otherwise, she might check out a book by someone she doesn’t know simply because of the cover design.

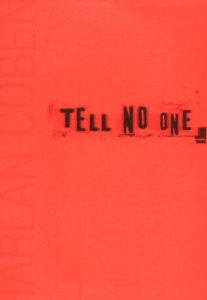

(This is exactly how I discovered Harlan Coben. I vividly remember going into Crown Books and looking at the New Release table, and one cover just jumped out and grabbed my shirt and said, “Open me!” It was the cover of Tell No One, and it was stunning, not just because of the color and title font, but also because Harlan’s name could not be seen. This counter-intuitive distinction set it apart from every other cover on that table.)

(This is exactly how I discovered Harlan Coben. I vividly remember going into Crown Books and looking at the New Release table, and one cover just jumped out and grabbed my shirt and said, “Open me!” It was the cover of Tell No One, and it was stunning, not just because of the color and title font, but also because Harlan’s name could not be seen. This counter-intuitive distinction set it apart from every other cover on that table.)

So what next? She will look at the dust jacket copy. Does that copy sizzle? Make the plot irresistible? If so, the next place she’ll turn is to the opening page. And of course we know what that has to do. Just check out our First Page Critique archives.

If she likes what she reads, our browser will look at the price. $28? Yikes! Ah, but B&N is offering it at a 30% new release discount. That might just be enough to close the sale.

It’s roughly the same with online browsing. Cover, book description, the “Look Inside” feature to sample the first pages, and the price. Understand that sequence as you plan your marketing.

So what about the second consideration, building buzz? The two primary venues for this are social media and the email list. The one overarching consideration is: Don’t annoy.

You annoy by only talking about your book and how great it is going to be. If all we see on social media is variations on “buy my book!” it’s not buzz, but “buzz off” we’re going to create.

My rule of thumb on social media is 90/10. Ninety percent of the time be, gasp, social, providing good content so people are glad to have you around. Then when a book comes out or you have other such news, you have the trust and toleration of your followers.

Everyone knows and touts the essentiality of the fan email list. It takes years to build a substantial list, which you do by a) writing great books; b) having a systematic way for readers to sign up; and c) making the actual content of your communication a pleasure to read.

So what do you do if you are just starting out and have no fan base? If you’re traditionally published, work in concert with your publisher and come up with a plan. While there are still physical bookstores around, introduce yourself locally and set up a book signing. Your publisher might be able to arrange a regional tour (travel expenses on you). Are book signings worth it? All pro authors can tell you stories about book signings gone awry (see this post from TKZ emeritus Joe Moore), but when you’re a newbie, you pay your dues.

For both traditional and self-publishing writers: send personalized emails to everyone you know, politely requesting they take a shot on your book and, if so moved, a) leave a review on Amazon; b) tell their friends about it; and c) sign up for your email list which, you assure them, won’t be spammy or too frequent. (My rule of thumb here is once-a-month, give or take.)

We all know how hard it is to get a message through amidst the din and dither of the madding crowd. Just remember to keep the main thing the main thing: write excellent books. That’s the only ironclad, long-tail secret to a career. Buzz and marketing help get you an introduction. They can turn browsers into buyers. But it’s your books that turn buyers into fans.

This is my last post of 2018. To my blogmates and all our marvelous TKZ readers: Merry Christmas and a Carpe Typem New Year!

Last week in the comments, Kay DiBianca wrote:

I sure would like to have a master list of the best books for learning the craft of writing.

You asked, you got it.

Now, modesty prevents me from mentioning my own books on the craft. If I was not the humble scribe that I am, I would probably say something like, “These books have proved extremely helpful to fiction writers,” and then I’d put a link to my website for a list of the books.

Instead, I will narrow my focus six books which I found most helpful when I was starting out. There’s that old saying, “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” Well, I was ready, and these books appeared. They helped lay a foundation for all my writing since.

Writing and Selling Your Novel by Jack Bickham

Apparently only available in hardback, this is the Writer’s Digest updated version of Bickham’s Writing Novels That Sell (which is the edition I studied). It was his treatment of “scene and sequel” that gave me my first big breakthrough as both a screenwriter and novelist. A light came on in my brain. It was a major AH HA! moment. Bickham’s style is accessible and practical, and a big influence on me when I began teaching. I wanted to give writers what Bickham gave me: nuts and bolts, techniques that work, and not a lot of fluff and war stories.

I found out that Bickham was running the writing program at the University of Oklahoma, where he himself had been mentored by a man named Dwight V. Swain. So I researched Swain, and discovered he’d been a writer of pulp fiction and mass market paperbacks, and written a book a bunch of writers swore by. So naturally I bought it.

Techniques of the Selling Writer by Dwight V. Swain

For those wanting to write commercial fiction (i.e., fiction that sells), this is the golden text. Swain takes the practical view of the pulp writer, the guy who had to produce gripping, ripping stories in order to pay the bills. He lays it all out in a perfect sequence for the new writer, who could go chapter by chapter, building a writing foundation from the ground up. I review my highlighted and sticky-noted copy every year.

Writing the Novel by Lawrence Block

Block was, for years, the fiction columnist for Writer’s Digest magazine. At the same time, he was a working writer himself, having come up through the paperback market and into a series character that has endured, the New York ex-cop Matthew Scudder. Thus, what Block brought to the table was the way a prolific writer actually thinks. The questions I was having as I wrote Block always seemed to anticipate and address. He opens the book with his timeless advice: “If you want to write fiction, the best thing you can do is take two aspirins, lie down in a dark room, and wait for the feeling to pass. If it persists, you probably ought to write a novel.”

Screenplay by Syd Field

This was, I believe, the first “how to” book I bought when I decided I had to try to become a writer. I started out wanting to write screenplays. With writers like William Goldman and Joe Eszterhas getting seven figures for original scripts, I thought, well, maybe this would be a good venture (the only more lucrative form of writing, according to Elmore Leonard, is ransom notes). Field’s book contains his famous “template,” which is a structure model. I studied movies for a year just looking at structure, and finally nailed it. What I added to Field was what is supposed to happen at the first “plot point.” I called it the “Doorway of No Return.” That discovery still excites me.

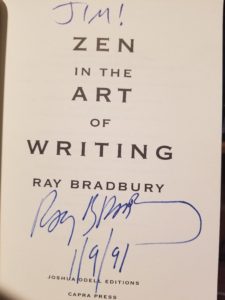

Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury

Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury

This is a right-brain book, and therefore a necessary balance. The secret to elevated writing is finding a way for the rational and playful sides of the writer’s mind to partner up. Bradbury’s book is full of the joy of writing, and it’s infectious. Two of my favorite quotes: “You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.” And: “Every morning I jump out of bed and step on a landmine. The landmine is me. After the explosion I spend the rest of the day putting the pieces together. Now, it’s your turn. Jump!” My signed copy is always within reach.

Stein on Writing by Sol Stein

Sol Stein, 92 years young, is a writer, editor, and publisher (he founded Stein & Day back in 1962). When I started out he had an innovative, interactive computer program called WritePro, which is apparently still available. Much of the advice in the program is in this book, including inside tips on point of view, dialogue, showing and telling, plotting, and suspense.

So there you have it. My list of the books that helped me most when I was starting out. The floor is now open to you, TKZers. What books have you found helpful in your writing journey?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Recently, in our comments, TKZ regular Harvey Stanbrough made reference to Robert A. Heinlein’s “Five Rules for Writers.” They are as follows:

Rule One: You must write.

Rule Two: You must finish what you start.

Rule Three: You must refrain from rewriting, except to editorial order.

Rule Four: You must put it on the market.

Rule Five: You must keep it on the market until it has sold.

I’d like to offer my commentary on this list.

Rule One: You must write.

Pretty self-evident. You can’t sell what you don’t produce. The writers of Heinlein’s era all had quotas. Pulp writers like W. T. Ballard and Erle Stanley Gardner wrote a million words or more a year. Fred Faust (aka Max Brand) wrote four thousand words a day, every day. They did so because they were getting a penny or two a word, and they needed to put food on the table.

I always advise writers to figure out how many words they can comfortably write in a week, considering their other obligations. Now up that number by 10% and make that the goal. Revise the number every year. Keep track of your words on a spreadsheet. I can tell you how many words I’ve written per day, per week, per year since the year 2000.

Rule Two: You must finish what you start.

I remember when I finished my first (unpublished, and it shall stay unpublished) novel. I was still trying to figure out this craft of ours and knew I had a long way to go. But I learned a whole lot just from the act of finishing. It also felt good, and motivated me to keep going.

Heinlein was primarily thinking about short stories here, so the act of finishing was an easier task. With a novel, there’s always a moment when you think it stinks. When you wonder if you should keep going for another 50k words. Fight through it and finish the dang thing. Nothing is wasted. At the very least you’ll become a stronger writer.

Should a project ever be abandoned? If you’ve done sufficient planning and have the right foundation, I’d say no. If you’re a pantser … well, the temptation to set something aside is more pronounced. But you chose to be a panster, so deal with it.

Rule Three: You must refrain from rewriting, except to editorial order.

This is a bad rule if taken at face value. Again, Heinlein was thinking about the short story market. With novel-length fiction, the old saw still applies: Writing is re-writing.

I’ve heard a certain #1 bestselling writer state that he only does one draft and that’s it. Upon closer examination, however, that writer is revising pages daily as he goes, so it comes out to the same thing—re-writing.

As for “editorial order,” Heinlein meant that once a story sold—which meant actual payment—you made the changes the editor wanted (that is, if you wanted him to send you the check!)

For all writers, a skilled editor or reliable beta readers give us an all-important extra set of eyes. Don’t skip this step. There’s always something you need to fix!

Rule Four: You must put it on the market.

Which, for Heinlein, meant sending the story out to the pulp or slick magazines. Or, in the case of a novel, to the authorities within the Forbidden City of traditional publishing.

Today, of course, we have one major advantage Heinlein did not: self-publishing. But that option does not mean you don’t need to go through the grinder of making a manuscript the best it can be.

Rule Five: You must keep it on the market until it has sold.

Again, this was about the old world of magazines. When a manuscript came back, rejected, you got another envelope and sent it out again. The pages could get pretty scuffed up that way.

Today, the big questions for the writer are: a) should I seek traditional publishing, or self-publish? b) if traditional, how many rejections should I endure before publishing on my own? and c) if going indie, how do I know my book is ready?

Sci-fi writer Robert Sawyer added a sixth rule that is crucially important:

Rule Six: Start Working on Something Else

That’s my own rule. I’ve seen too many beginning writers labor for years over a single story or novel. As soon as you’ve finished one piece, start on another. Don’t wait for the first story to come back from the editor you’ve submitted it to; get to work on your next project. (And if you find you’re experiencing writer’s block on your current project, begin writing something new — a real writer can always write something.) You must produce a body of work to count yourself as a real working pro.

So what do you think of Heinlein’s rules (and Sawyer’s addendum)? What else would you add?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Next year will be my 24th as a professional writer.

When my first book hit the shelves nobody used a cell phone (Seinfeld had that big brick handset with the antenna, remember?) O.J. Simpson had been found not guilty and Bill Cosby was still America’s most beloved dad. Microsoft released Windows 95. And a guy named Bezos launched a website that was purportedly going to sell books to consumers right over the internet! Everybody thought he was nuts.

For the seven years previous I’d been studying the craft of screenwriting and fiction, and writing every day. I devoured books on writing and gobbled up each monthly issue of Writer’s Digest. I have several shelves of my beloved writing books (and binders full of WDs), all highlighted and sticky-noted in some form or fashion. Every so often I like to pull one off the shelf to see what I highlighted, and relive some of the excitement of discovering something that worked for me.

The other day took down The Complete Guide to Writing Fiction by Barnaby Conrad, published by Writer’s Digest Books. It’s a collection of articles and interviews from the famous Santa Barbara Writers Conference, which Conrad directed for many years.

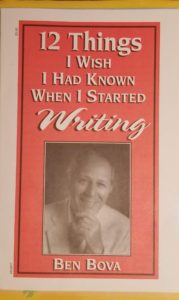

There was something tucked inside the book. It was a pamphlet titled 12 Things I Wish I Had Known When I Started Writing by Ben Bova, the science-fiction writer and editor. I think this came as a freebie with a book ordered from the Writer’s Digest Book Club, of which I was an enthusiastic member. So I had another look at Bova’s lessons and thought I’d reflect on them with you today. The first two are unsurprising:

There was something tucked inside the book. It was a pamphlet titled 12 Things I Wish I Had Known When I Started Writing by Ben Bova, the science-fiction writer and editor. I think this came as a freebie with a book ordered from the Writer’s Digest Book Club, of which I was an enthusiastic member. So I had another look at Bova’s lessons and thought I’d reflect on them with you today. The first two are unsurprising:

All serious writing students know this, though I would edit the first one thus: write to a weekly quota. Figure out how many words you can comfortably write in a week, then up that by 10% for your goal.

Bova stresses the importance of well-rounded characters. Basic, of course, but coming from the sci-fi genre Bova knows it’s a temptation to overemphasize world-building.

I would change Problem to Plot, where plot is defined as a life-or-death battle which the character meets by strength of will.

This is Bova’s most important tip. The “villain” does not see himself that way. “Every tyrant in history was convinced that he had to do the things he did, for is own good or for the good of the people around him,” Bova writes.

I always counsel writers to know the bad guy’s “closing argument.” If he were on trial, what would he say to defend himself? And mean it?

My heart sang. Had Bova anticipated Write Your Novel From the Middle? Ahem. No. He was talking about the opening pages, and he echoes one of my constant refrains: act first, explain later. Bova explains:

[Start] your story in the midst of brisk, exciting action. Start in the middle! Don’t waste time telling us how your protagonist got into the pickle he’s in. Show him struggling to get free. You can always fill in the background details later.

Particularly in a novel, it’s tempting to set the scene, explain the protagonist’s background, describe how she got to where she is. Cut all that out. Or, at least, save it for later. Start in the midst of action. Hook that reader right away or you won’t hook him at all.

Don’t present a problem on page one and then solve it. Pile them up. “Each problem you present to the protagonist is a promise to the reader that there will be suspense, excitement, adventure in solving that problem.”

Bova rightly notes that writers tend to favor sight and sound. Add touch, taste, and smell.

Bova makes a case for close 3d Person, so you can be intimate with a character in one scene, then cut away to another character, and so on. He does not favor First Person because he finds it too limiting. Hmm. Tell that to Raymond Chandler.

The last three tips come from another world, when hard-copy manuscripts were submitted to agents and editors. Imagine that!

“Typed, whether on a typewriter or a computer printer.”

Remember when that was an actual choice?

“Publishers think in categories. You must too.”

“And always remember to include the SASE.”

(For you kids out there, SASE stands for “Self-Addressed Stamped Envelope.” Ask your parents what that means.)

All this got me thinking: what is something I wish I’d known when I started out? I’ll give you a twofer:

I wrote four or five screenplays that didn’t generate any interest. What finally broke me through was an epiphany while reading Jack Bickham’s Writing Novels That Sell. Specifically, his chapter on scene and sequel. More specifically, understanding the scene beats of Goal, Conflict, Disaster. No more weak or meandering scenes after that. The next script I wrote got me an agent.

The initial thrill of being published eventually ran into a new set of challenges familiar to all writers who make it inside the gates of the Forbidden City. Stuff like comparison, envy, self-doubt, bad reviews. All of which interfere with the joy of writing. Faith and family were in place for me, but I also studied specific topics like gratitude, contentment, focus, and discipline. So important are these that I wrote a book to help writers prepare for and deal with the mental game of writing.

So, TKZers, if you’ve been around the block, what is something you wish you had known when you were starting out?

And if you are just starting out, what is something you want to know? Ask away, and one of our crack team of bloggers will take a flyer at an answer—for I am in travel mode today and my check-in may be sketchy.

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Those of us who teach as well as write are always glad to hear that something we suggested helped a fellow scribe. I got an email the other day that I have to share. With the kind permission of the sender, here it is:

Those of us who teach as well as write are always glad to hear that something we suggested helped a fellow scribe. I got an email the other day that I have to share. With the kind permission of the sender, here it is:

Dear Mr. Bell

I want to thank you. You helped me find something that I had no idea I had in me.

A few minutes ago, while reading your book “Plot & Structure”, I completed Exercise 1. As per your instruction, I wrote from the gut. [JSB: This is a free-form, just let-er-rip exercise, no judging or stopping, asking yourself what kind of writer you wan to be.]

The result surprised me deeply. I never knew that I could write something like that 15 minutes ago, and I never realized the kind of author I want to be.

As a thank you, I am including in this email the text I wrote. It is exactly the way I first wrote it, and I haven’t even read it myself yet:

“When readers read my novels, I want them to feel that they have just been on a journey to a new world, a different universe. I want them to feel amazed, I want them to feel like they have never read anything like that before in their lives, I want them to feel that if they want to experience this kind of suspense again, they have to read my stories. I want them to think about what they read the next day, the next year, I want the story they read to mean so much to them that they will be planning to show it to their unborn children one day. And most important of all, I want them to keep wanting more at the end.

That’s because, to me, novels are a way for me to share my soul. Novels are the sum of all that is important in life, the sum of all of the things that make us smile, laugh, cry, scream, terrified, look over our shoulders on a dark alley, everything that we hope one day happens to us. They are our hopes, our fears, our dreams and nightmares, what elevates us to heaven one day and crushes us back to the earth with the might of a thousand heavens the next. A good story is a communion, it is something that a billion people who have never met each other share, it is a way for everyone to look up to the sky, or deep inside themselves, and recognize the same truth as any person might one day realize, no matter how far apart in space or time those people might live. It is a timeless truth, it is the very fabric of our souls, it is how we recognize each other and how we recognize ourselves in others. It is what makes us, us.”

It might be terrible in the end, but it meant a lot to me.

***

JSB: That is anything but terrible. It can’t be, for there is no wrong answer so long as it has come from your deepest self. Indeed, this young man got precisely the best result because it surprised him. Self-discovery is a crucial step toward writing unforgettable fiction.

This writer has taken that step.

And so I ask you, TKZers: Why do you write?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

One hundred years ago on this very day, the armistice ending the “war to end all wars” was signed just outside the city of Compiègne, France.

World War I, as it is now known, was a bloodbath, an unleashing of horrors heretofore unknown by humankind. From machine guns (“the devil’s paintbrush”) to phosgene gas, technology had overtaken military tactics, resulting in a massive scale of death.

One of those was my great uncle, Frederick “Ted” Fox, a Marine. He died in the Battle of Belleau Wood and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The longest book I ever wrote was the historical, Glimpses of Paradise. It begins in 1916 Nebraska and ends in early 1920s Hollywood. In between is a World War I sequence that was the result of intense research.

Which raises a natural question: how do you write about experiences you’ve never had? I’ve never been to war. Does that mean I can’t write about it? I obviously didn’t think so when I wrote Glimpses. So here’s what I did:

How about you? Have you ever written way outside your experience? What did you do to get it right? Please tell us in the comments!

And please pause a moment this Armistice Day to honor those men who gave the last full measure of devotion for our country a century ago.

Also, my film professor son alerted me to a new documentary by Peter Jackson about soldiers in World War I. The talented Jackson took old, herky-jerky silent film footage, digitized it and used computerization to connect the frames and make all the movements natural. Then he colorized the footage.

The stunning result is a view of The Great War as we have never seen it. I hear it will blow you away. Here’s the official trailer:

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Gustave Flaubert (1821 – 1880) was, of course, the French novelist known primarily for his masterpiece, Madame Bovary. He was a man of tremendous passion and ambition. His greatest desire, from a young age, was to become a world-class novelist.

At the age of 24, Flaubert was mesmerized by a painting depicting the temptation of St. Anthony. It inspired his first attempt at a novel. Flaubert worked on it off and on for the next five years, finally completing a 500 page manuscript in 1849.

Now what?

Flaubert had two close literary friends, Maxime Du Camp and Louis Bouilhet. He called them to his home in Croisset on the condition that they listen to him read the entire manuscript out loud, not uttering a single word until he was done!

Yeesh.

Just before the reading began, Flaubert declared, “If you don’t cry out with enthusiasm, nothing is capable of moving you!”

Then he began to read. Two four-hour sessions per day!

Flaubert ended a little before midnight on the fourth day. The exhausted would-be novelist put down the last page and said, “It is your turn now. Tell me frankly what you think.”

Du Camp and Bouilhet were in agreement that the latter should speak for them both.

Bouilhet cleared his throat and said, “We think you should throw it in the fire and never speak of it again.”

Now that is what you call a short and sweet critique.

The reaction, as described by Prof. James A. W. Heffernan in a lecture on Flaubert, was as follows:

Flaubert was flabbergasted. And of course he did talk about it—the three of them argued about it heatedly all through the night, right up until eight o’clock the next morning—with Flaubert’s mother listening anxiously at the door. Flaubert defended it as best he could, pointing out fine passages here and there, but fine passages alone don’t make a good book. His friends saw no progression in the story, no vitality in the figure of St. Anthony himself, no real grip on the theme. Essentially, they argued, Flaubert had taken a vague subject and made it vaguer. He had fatally indulged his own Romantic tendency toward lyricism—toward the fantastic, toward the mystical. To get a grip on these tendencies, Flaubert needed something that could not be treated lyrically.

Flaubert’s two friends did not let him wallow in despair. Instead, they gave him some advice that would change his writing forever. Don’t try to tackle some big theme in a lyrical manner, they told him. Write about something down-to-earth, and do it in a naturalistic style. Prof. Heffernan recounts:

On the day after the long night of the argument, the three friends took a walk through the gardens of Croisset by the River Seine. According to Maxime du Camp, Bouilhet suddenly proposed that Flaubert write a novel based on the true story of a public health officer whose second wife committed adultery, got herself into debt, and then poisoned herself.

Flaubert took their advice. In 1851 he began writing his second novel, Madame Bovary.

The lessons here:

Do you have trusted beta readers? How have they helped you?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

It’s no secret that I love the paperback era of the 1950s. Most of it is eminently entertaining, and almost always well written. Why? Because the writers in those days had been through the classic American schooling that drummed the structure of the English sentence into their heads. Then they paid their dues writing for newspapers, where grizzled editors would scream at them to write more clearly.

It’s no secret that I love the paperback era of the 1950s. Most of it is eminently entertaining, and almost always well written. Why? Because the writers in those days had been through the classic American schooling that drummed the structure of the English sentence into their heads. Then they paid their dues writing for newspapers, where grizzled editors would scream at them to write more clearly.

The result was sharp and grammatical prose, unlike so much of what’s produced today, even in once respected newspapers. I recently saw the word anyways in an actual news column trying to make an actual point.

But I digress.

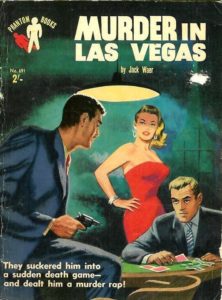

I recently purchased The Noir Novel Megapack—four 1950s novels for only 55¢! A few days ago I started reading one of them: Murder in Las Vegas by Jack Waer.

It’s terrific. A solid noir set up: After a night of drinking and getting into a fight, a guy wakes up in his apartment, not knowing how he got there. He finds his .38 on the floor and picks it up. Then he spots a dead body on his bed just as his cleaning lady comes in and, seeing the gun in his hand and the body on the bed, screams and runs out. It isn’t long before he’s on the lam and hiding out in L.A.

Excellent hardboiled prose, as in:

His fist came up into my face and it was like having a stick of dynamite exploding inside my head. That was the end of the line. After that there was nothing but the black velvet road that led me through insane dreams.

***

Slowly, I crossed around the bed. I went just so far, then stopped, although the thing inside my gut sprang forward, clawing and spitting. I wanted to yell, to scream out all the filthy things I’d ever learned in all those years on the way up. I wanted to yell until the noise drove away the sight in front of me.

Somebody had been at her throat with a knife.

***

I grabbed the threadbare huck towel off the rack and splashed some water on my face. After I’d dried off I took a look at myself in the mirror and decided never to do it again.

***

The Vanguard was the address where the high tone and six-figure sports kept their private doxies in the manner to which their wives had never been accustomed.

***

The place reminded me of my happy childhood. It was like Old Home Week to enter the dark interior and smell the sweetish odor of stale beer, dampness and despair.

So I found myself wondering, who was Jack Waer? But my initial searches hit a cul-de-sac.

On Amazon, there are only three titles listed for him, as used paperbacks. Murder in Las Vegas, Sweet and Low-Down and 17 and Black.

Who was this guy? I didn’t find any biography of him on the usual noir sites. He was not listed in my go-to reference on this era, Paperback Confidential: Crime Writers of the Paperback Era. I even emailed an MWA Grand Master who is an expert in the pulps. He’d never heard of the guy.

I began to formulate a theory. Because the writing in Murder in Las Vegas is so sharp and spot-on, I thought “Jack Waer” might be a pseudonym for a mainstream novelist. In those days, literary writers often went “slumming” in paperback originals in order to make some dough on the side, all while protecting their “good name.” Evan Hunter did that under the pseudonym Ed McBain. It was McBain who became rich and famous. I don’t know if Hunter ever forgave his alter ego for that.

So that was my theory. Only three books. (It turns out it’s only two, for Sweet and Low-Down is a reissue of 17 and Black with a new title.)

Did he die? Or did the literary author simply move on?

It turns out I could not have been further off.

I did another search on Google and saw an old black and white photo:

So I went to the page, which turned out to be the blog of L.A. mystery writer J. H. Graham. Ms. Graham is, like me, third-generation Angeleno, and we both love the crime lore of the 50s. I am indebted to her for solving the Jack Waer mystery.

Turns out Waer was a gambler running in the same circles as Mickey Cohen, the underworld king of Los Angeles. Says Graham:

Waer, who is also used the name Alexander John Warchiwker according to his naturalization forms, was born in Warsaw Poland in February 1896. He came to Los Angeles sometime after 1930, having previously lived in Detroit. In 1942 he listed Eddie Nealis as his employer on his WWII draft registration card; his job description was not specified. However, he was arrested on gambling charges in July 1943, when D.A. investigators raided an office in the Lissner Building at 524 S. Spring St. and found Waer running a dice game.

The [Los Angeles] Times had called Waer a writer after the NYE 1945 hold-up. He may well have been one; In any case, he became a writer for sure by 1954 with publication of his novel 17 and Black (later issued in paperback as Sweet and Lowdown).

So there you have it. A habitué of the illegal gambling dens of 1950s Los Angeles wrote a couple of books on the side, one of which is pretty doggone good!

Even if your beat is the underbelly of society, it helps if you can write.

Waer, according to Graham. died in Las Vegas in 1966.

And if you are interested in crime fiction that takes place in Los Angeles back in those days, check out J. H. Graham’s mysteries.

What obscure writers have you come across who should be better remembered?