Most writers hope we’ll have long-running series: John Sandford has written 32 Prey thrillers, featuring Lucas Davenport. Sue Grafton’s alphabet series has 25 mysteries, and with her untimely death, the alphabet ended at the letter Y. And Marcia Talley has written 19 Hannah Ives mysteries since 1999. She’s managed to take her series to three publishers, a nearly impossible feat.

Booklist magazine said this about her latest mystery, Disco Dead, which debuted in November, “Some long-running series have their ups and downs, but the Ives series has been remarkably consistent.”

We’ve asked Marcia about her long-lasting series, and how she’s kept up the quality.

– Elaine Viets

Elaine: Who is Hannah Ives, and why did you create her?

Marcia: I don’t have to tell you that the real world is a messy, violent, frequently unjust place. Mysteries can be a respite – in my fictional world I call the shots. Justice is served and the villain suitably punished. I love the puzzle aspect of the mystery, planting clues and dropping red herrings. As for me personally, there have been a lot of people in my life who needed to die. In a mystery, I can bump them off with a stroke of my pen, and it’s cheaper than a therapist. I’ve bumped off former bosses, an ex-brother-in-law, a real estate agent, a crooked developer (the list goes on!) and even my husband a couple of times.

Elaine: How much of you is in Hannah?

Marcia: Is she my alter ego? Yes and no. She reminds me a bit of what Nancy Drew would be like at 55 or so. Like me, Hannah is a breast cancer survivor who enjoys sailing and is married to a professor at the Naval Academy. She’s funnier than I am, though, and braver—I would never break into a doctor’s office and riffle through his medical records, but Hannah would. Hannah’s younger and prettier, too, although just as curious and fiercely independent.

Her name was always Hannah, by the way, but I didn’t realize until my first editor emailed to inquire about it that my heroine didn’t have a last name. In a semi-panic, I called a friend who suggested the name Ives. I found out later that my friend’s phone was mounted on a kitchen wall next to a Currier & Ives illustrated calendar, so Hannah might well have been named Hannah Currier.

Elaine: How was your first Hannah mystery received?

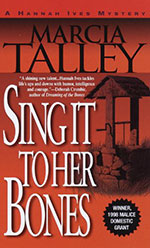

Marcia: It still amazes me! Sing It to Her Bones won the Malice Domestic Grant for unpublished mysteries, then, after it was published by Bantam Dell, was nominated for an Agatha Award for best first novel. At the Malice Domestic conference that year, I appeared on a panel with the other nominees that was moderated by Margaret Maron (I was such a fan girl!). Hannah lost out to Donna Andrews and her wrought-iron flamingos, but the boost the award gave me spurred sales. Reviews were uniformly positive – “a shining new talent” OMG! – and I was thrilled to get cover blurbs from mystery authors I admired tremendously like Margaret, Laura Lippman, Sujata Massey and Deborah Crombie.

Elaine: Cancer is a grim topic. How do you keep Hannah entertaining?

Marcia: With humor and pragmatism. The opening lines of Sing It to Her Bones are:

“When I got cancer, I decided I wasn’t going to put up with crap from anybody anymore.”

And over the course of the next nineteen novels, she certainly doesn’t.

Take this example in a scene from the first chapter of Sing It to Her Bones. Here, Hannah is receiving the devastating news that she’s being laid off from the prestigious D.C. accounting firm she’s worked at for years:

While Coop oozed on about severance pay and maintenance of health benefits, I stared at Fran, who sat straight-backed and immobile, like an ice sculpture. I willed her to look at me, but she focused on his reflection in the tabletop. If Jones of New York had issued shotguns along with its suits, I thought, Old Cooper’s shirtfront would have been a sodden mass of red and we would have been picking bits of lung and rib out of the oriental carpet. I concentrated on the way his yellowish hair sprouted from his upper forehead in spiky clumps and how his earlobes wobbled when he talked. Frankly, when he laid the news on me, I didn’t know whether to run out and hire a lawyer to sue his ass or fall down and kiss his feet.

Elaine: Who was your first publisher and why were you dropped?

Marcia: My first contract was a three-book, mass-market paperback deal with Bantam Dell, a division of Random House. At some point between Unbreathed Memories and Occasion of Revenge, Random House was bought out by the German publishing giant, Bertelsman and their whole mass-market paperback mystery line was axed. Up until that time, B/D had been publishing two paperback mysteries a month; twenty-four authors were instantly orphaned. I remember (barely!) commiserating with a bunch of homeless B/D authors around the bar at Bouchercon Denver in September of 2000.

Elaine: Were you expecting your series to be canceled? What did you do when you got the news?

Marcia: I was completely blind-sided. My then editor had already told my agent that they would be wanting a fourth book in the series. I got the bad news on my cell phone, directly from my editor while sitting in a parking lot outside a Shaw’s supermarket near my sister’s home in Gorham, Maine. After sulking for a while, I marched into the store and bought a pint of Haagen Dasz rum raisin ice cream and ate it all by myself.

Elaine: Conventional wisdom says when publishers drop writers, these authors have two choices: indie publish their series, or start a new series. Did you consider either alternative?

Marcia: Back in 2001, indie publishing was about as respectable as printing your manuscript out at Kinko’s and selling it out of the trunk of your car, so it was never a consideration for me. Conventional wisdom at the time was to Keep Your Name Out There. So, I began to write short stories, the first of which, “With Love, Marjorie Ann” was short-listed for an Agatha award. Fans of my Hannah Ives mysteries will be surprised to learn that I am also a serial novelist. I wrote novels with other women. And not just one woman either. TWELVE other women.

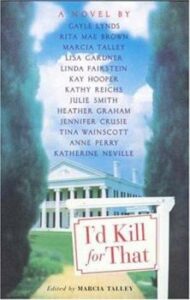

My then agent called shortly after the aforementioned rug had been pulled out from under me, to say he’d heard that some publisher had paid Big Bucks for a serial novel about golf. He suggested I write a novel set in an exclusive health spa, with, say, a greedy owner, a star-struck daughter, a drunken senator, an aged rock star … and Naked Came the Phoenix was born. Naked was followed by I’d Kill for That, my second expedition into collaborative serial novel territory. For the uninitiated, let me explain that the novel, like its predecessor, was written in round-robin style: one author writes the first chapter then passes it to the second who picks up the story where the first author left off, then passes it on to the third, and so on.

For me, coming up with the scenario – murder in an exclusive gated community — and creating a smorgasbord of fascinating characters for the others to play with was just the beginning. The fun really started when I turned it all over to my fellow authors, sat back and waited to see where my dream team would run with it, and they didn’t disappoint.

Under the talented pen of Gayle Lynds, the “greedy real estate developer” suggested in my proposal leapt to life “with a clash of cymbals and a drum roll” as Vanessa Smart Drysdale, a petite, chestnut-haired beauty in black leather slacks who possesses all the compassion of Cruella de Vil. Little did I know what Lisa Gardner had in store for poor, tormented Roman Gervase, and Julie Smith’s take on Sunday services at St. Francis of Assisi Interfaith Chapel had me chuckling for weeks. Other equally delightful chapters were penned by Rita Mae Brown, Linda Fairstein, Kay Hooper, Kathy Reichs (lending her customary forensic expertise, of course), Heather Graham, Jennifer Crusie, Tina Wainscott, Anne Perry, Katherine Neville and, ahem, me.

The authors seemed to enjoy the game, too. The rules were simple. Each chapter was to be written in the third person, with a definite solution in view, even thought we were well aware that subsequent authors might take – indeed were expected to take – the plot in divergent directions. Speaking of her chapter in Naked Came the Phoenix, which was set in a luxury health spa in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, Nancy Pickard said, “It was dangerously liberating to know I didn’t personally have to deal with the consequences of whatever I put in my chapter.” Good thing, too, as she left our heroine struggling to extract the body of the spa owner from a mud bath.

Although writers were cautioned to avoid cliff-hanger endings that would require Houdini-like efforts on the part of the next author, the “real fun” comes, according to Laurie R. King who wrote the final chapter of Naked Came the Phoenix, “in seeing thirteen sweet-tempered lady crime writers stab each other thoughtfully in the back.” Judy Jance gleefully ended her chapter in that novel with Phyllis, the spa’s resident psychic, floating face down in a lake. Fortunately, however, someone in Faye Kellerman’s chapter knew CPR and revived Phyllis long enough for her to deliver a critical clue before lapsing into a coma.

As you might guess, my job as editor/contributor resembled a cross between tour guide and traffic cop as I assembled the team and worked out the intricacies of scheduling – each author had just a month to complete her chapter – and made sure, for example, that each author received packets of background information and copies of the chapters that preceded hers. Timing was critical. We met at conferences, spoke on the telephone and exchanged emails at a furious rate. As we raced to the finish line, Anne, Katherine and I kept the trans-Atlantic telephone lines hot as we brainstormed and worked out plot details – Anne Perry pointed out that the novel needed a love story, and she was right – so we put one in. And Val McDermid vowed she would not participate unless she could use the word “incarnadine,” a request I happily granted. Often we found ourselves revisiting an earlier chapter to plant a clue or clear up a discrepancy, and it fell to the amazing Katherine Neville – who volunteered for the job, I should point out – to tie up all the loose ends as our novel sprinted to its stunning conclusion.

Elaine: How many books did you do with your second publisher, and why did you jump to a third?

Marcia: My second publisher was Morrow/Avon. I don’t think it’s any coincidence that the very night I won the Agatha Award for my short story, “Too Many Cooks” in 2002, I was approached at the awards banquet by Caroline Marino, a senior editor at M/A who was well aware of the bloodbath that had taken place over at B/D and said, “I have someone I’d like you to meet.” Caroline was already familiar with the Hannah series and introduced me to editor Sarah Durand. Within a week, my agent received an offer of a 3-book deal. In Death’s Shadow, This Enemy Town and Through the Darkness were all published by Morrow/Avon until they met the same fate as my first three books: the victim of a corporate takeover, this time by Harper Collins, and a decision to ax the mass market mystery line in favor of trade paper format. I was already well along with Dead Man Dancing, set in the world of competitive ballroom, which was immensely popular at the time with TV shows like “Strictly Come Dancing” in the UK and “Dancing with the Stars” in the US, so that may have been one reason the series was picked up by Severn House. I’ve been with them ever since.

Elaine: How has Hannah changed since your first book?

Marcia: If I had known when I was writing Sing It to Her Bones that I was writing a series, I would have made Hannah much younger. At the end of the first book, we learn she’s about to become a grandmother. My novels are roughly contemporaneous—Occasion of Revenge, for example, climaxes during New Year’s Eve celebrations in 1999, the eve of the New Millenium – so Hannah must be at least twenty-two years older than she was back then, but, uh, let’s not mention it.

Elaine: What do you do to keep your series fresh?

Marcia: Every time I finish a book, I think, “I’ll never get an idea for another one.” But all one needs to do these days is pick up a newspaper or watch television to find something that gets the creative juices flowing. The first thing I ask is how do I get Hannah believably involved in this? Writers of mystery series call it avoiding the Cabot Cove Syndrome. After twelve seasons of “Murder She Wrote” and years in syndication, there can’t be anyone left alive in Cabot Cove, Maine, and would you risk having tea with Jessica Fletcher? Once I figure out how to involve Hannah – and her network of cancer survivors is a big help there – I hop on the Internet and begin researching the issue. In Mile High Murder, for example, Hannah is invited to go on a fact-finding trip to Denver, Colorado by a Maryland state senator in their cancer support group who is looking into legalizing recreational marijuana in Maryland. In Tangled Roots, I explored what happens when Hannah’s Ancestry.com DNA test comes up with totally unexpected results. The expertise she gained with forensic genealogical research in that novel and the subsequent one, leads her to being invited to join a small group of quirky “citizen detectives” dedicated to solving cold cases in my latest novel, Disco Dead.

Marcia and her husband Barry are sailors, and spend winters in the Bahamas. Here’s Marcia (with a broken finger, no less) writing her novel on their boat, Iolanthe.

Elaine: Thank you, Marcia for an informative interview. TKZers, you can buy Sing It to Her Bones here: https://www.amazon.com/Sing-Bones-Hannah-Ives-Mystery/dp/0440235170?ie=UTF8&qid=1464306300&ref_=tmm_mmp_swatch_0&sr=1-1

And this is the link for Disco Dead: https://www.amazon.com/Disco-Dead-Hannah-Ives-Mystery/dp/1448307953/ref=sr_1_1?crid=AUSQ28331C5Y&keywords=disco+dead+marcia+talley&qid=1670508658&sprefix=disco+dead%2Caps%2C1810&sr=8-1

I’m lucky. Unlike many writers, I have a helpful husband, and the luxury of an office in my home. I don’t have children or relatives to care for. I’m a full-time author and don’t have to go to a job.

I’m lucky. Unlike many writers, I have a helpful husband, and the luxury of an office in my home. I don’t have children or relatives to care for. I’m a full-time author and don’t have to go to a job.

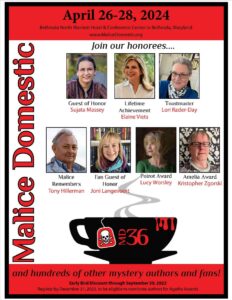

The Malice Domestic mystery conference is honoring me with the Lifetime Achievement Award for Malice 36 April 26-28, 2024. Malice Domestic is an annual fan convention in Bethesda, Maryland. I’m thrilled to be part of a star-studded line-up next year.

The Malice Domestic mystery conference is honoring me with the Lifetime Achievement Award for Malice 36 April 26-28, 2024. Malice Domestic is an annual fan convention in Bethesda, Maryland. I’m thrilled to be part of a star-studded line-up next year. By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets

(1) Readers hate dream sequences.

(1) Readers hate dream sequences.

Personally, I wish writers would know the difference between grizzly and grisly murders. While it’s true the Cocaine Bear and some bears in the wild do kill humans, in most mysteries humans performing those grisly murders.

Personally, I wish writers would know the difference between grizzly and grisly murders. While it’s true the Cocaine Bear and some bears in the wild do kill humans, in most mysteries humans performing those grisly murders.

– “Connie Ogle and Susan Dee have had it with ‘lip biting.’ Ogle explains, ‘If real people bit their lips with the frightening regularity of fictional characters, our mouths would be a bloody mess.’

– “Connie Ogle and Susan Dee have had it with ‘lip biting.’ Ogle explains, ‘If real people bit their lips with the frightening regularity of fictional characters, our mouths would be a bloody mess.’ And I’m with Tobin Anderson, who wrote, “Vomiting is the new crying. I think it’s part of the whole hyper-valuation of trauma — and somehow tears seem too weak, too mundane. But imagine a funeral filled with upchuckers.” I’m seeing a lot of barfing on TV these days, and watching folks toss their cookies while I’m eating in front of the tube makes me want to . . . well, you get the point.

And I’m with Tobin Anderson, who wrote, “Vomiting is the new crying. I think it’s part of the whole hyper-valuation of trauma — and somehow tears seem too weak, too mundane. But imagine a funeral filled with upchuckers.” I’m seeing a lot of barfing on TV these days, and watching folks toss their cookies while I’m eating in front of the tube makes me want to . . . well, you get the point. By Elaine Viets

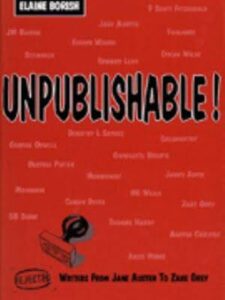

By Elaine Viets Not as catchy as Fifty Shades of Grey, is it?

Not as catchy as Fifty Shades of Grey, is it? I expected to be hit by lightning just for reading this title: Jesus Potter Harry Christ: The astonishing relationship between two of the world’s most popular literary characters: a historical investigation into the mythology and literature of Jesus Christ and the religious symbolism in Rowling’s magical series.

I expected to be hit by lightning just for reading this title: Jesus Potter Harry Christ: The astonishing relationship between two of the world’s most popular literary characters: a historical investigation into the mythology and literature of Jesus Christ and the religious symbolism in Rowling’s magical series.

And here’s a really trashy novel: Dumpsterotica: How Dirty Are You? Described as an “erotic comedy series,” this short story “puts the ‘rot’ in erotica; after reading this you’ll never look at a Dumpster the same way again.”I’ve already changed my mind about Dumpsters.

And here’s a really trashy novel: Dumpsterotica: How Dirty Are You? Described as an “erotic comedy series,” this short story “puts the ‘rot’ in erotica; after reading this you’ll never look at a Dumpster the same way again.”I’ve already changed my mind about Dumpsters. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society also made the list. I liked the book and the movie, but the cover has nothing to do with the title.

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society also made the list. I liked the book and the movie, but the cover has nothing to do with the title.

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets Murder seems to touch us all. When I thought about it, I realized I’d watched a murderer grow up in my city neighborhood. We lived on a shady street with big, old redbrick houses. One house, halfway down the block, was known as “the trouble house.” The police were there two or three times a week. The neighbors often called the cops on the boy, who I’ll call Billy, because that’s not his name. Billy broke windows, supposedly stole things out of yards, and may have tortured a stray cat.

Murder seems to touch us all. When I thought about it, I realized I’d watched a murderer grow up in my city neighborhood. We lived on a shady street with big, old redbrick houses. One house, halfway down the block, was known as “the trouble house.” The police were there two or three times a week. The neighbors often called the cops on the boy, who I’ll call Billy, because that’s not his name. Billy broke windows, supposedly stole things out of yards, and may have tortured a stray cat. In 2020, some 17,754 people were murdered in the USA. More than 40 people are murdered every day in the US. That statistic led to a jury room full of raised hands, and lives filled with sorrow and regret.

In 2020, some 17,754 people were murdered in the USA. More than 40 people are murdered every day in the US. That statistic led to a jury room full of raised hands, and lives filled with sorrow and regret. Late for His Own Funeral “ is a fascinating exploration of sex workers, high society, and the ways in which they feed off of one another.” — Kings River Life. Buy it here:

Late for His Own Funeral “ is a fascinating exploration of sex workers, high society, and the ways in which they feed off of one another.” — Kings River Life. Buy it here:

George Orwell had his masterpiece, “Animal Farm,” turned down by no less than T. S. Eliot, a big deal at UK publishers Faber and Faber. Like many in the upper echelons of publishing, Eliot missed the point when he rejected Orwell: “Your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm . . . What was needed (someone might argue) was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

George Orwell had his masterpiece, “Animal Farm,” turned down by no less than T. S. Eliot, a big deal at UK publishers Faber and Faber. Like many in the upper echelons of publishing, Eliot missed the point when he rejected Orwell: “Your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm . . . What was needed (someone might argue) was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.” Publishers outdid themselves with boneheaded reasons to reject bestsellers. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” was turned down by the prestigious Cornhill magazine because it was too much like the other “shilling shockers” already on the market. The editor said it was too long “and would require an entire issue” – but it was “too short for a single story.” Another publisher sent the manuscript back unread. A third bought the rights for a measly twenty-five pounds, and let it sit around for year. It was published in 1887, and then brought out as a book, but Conan Doyle didn’t get any money from that because he’d sold the rights. Worse, the book was pirated in the U.S. Doyle wrote a couple of historical fiction works. Then an American editor, looking for UK talent, had dinner with Doyle and Oscar Wilde and signed them both up. Wilde wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray” and Doyle did “The Sign of the Four.”

Publishers outdid themselves with boneheaded reasons to reject bestsellers. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” was turned down by the prestigious Cornhill magazine because it was too much like the other “shilling shockers” already on the market. The editor said it was too long “and would require an entire issue” – but it was “too short for a single story.” Another publisher sent the manuscript back unread. A third bought the rights for a measly twenty-five pounds, and let it sit around for year. It was published in 1887, and then brought out as a book, but Conan Doyle didn’t get any money from that because he’d sold the rights. Worse, the book was pirated in the U.S. Doyle wrote a couple of historical fiction works. Then an American editor, looking for UK talent, had dinner with Doyle and Oscar Wilde and signed them both up. Wilde wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray” and Doyle did “The Sign of the Four.”