It’s Winter break here at the Kill Zone. During o![AWREATH3_thumb[1] AWREATH3_thumb[1]](https://killzoneblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/AWREATH3_thumb-25255B1-25255D_thumb-25255B1-25255D.gif) ur 2-week hiatus, we’ll be spending time with our families and friends, and celebrating all the traditions that make this time of year so wonderful. We sincerely thank you for visiting our blog and commenting on our rants and raves. We wish you a truly blessed Holiday Season and a prosperous 2014. From Clare, Jodie, Kathryn, Kris, Joe M., Nancy, Jordan, Elaine, Joe H., Mark, and James to all our friends and visitors, Seasons Greeting from the Kill Zone. See you back here on Monday, January 6. Until then, check out our TKZ Resource Library partway down the sidebar, for listings of posts on The Kill Zone, categorized by topics.

ur 2-week hiatus, we’ll be spending time with our families and friends, and celebrating all the traditions that make this time of year so wonderful. We sincerely thank you for visiting our blog and commenting on our rants and raves. We wish you a truly blessed Holiday Season and a prosperous 2014. From Clare, Jodie, Kathryn, Kris, Joe M., Nancy, Jordan, Elaine, Joe H., Mark, and James to all our friends and visitors, Seasons Greeting from the Kill Zone. See you back here on Monday, January 6. Until then, check out our TKZ Resource Library partway down the sidebar, for listings of posts on The Kill Zone, categorized by topics.

Monthly Archives: December 2013

Literary Fiction and Me: A Complicated Love Story

Last week’s dustup in the comments, begun by my good friend Porter Anderson, and continued by him on The Ether, may have left the impression that your humble correspondent is a dastardly assassin of literary fiction, ready to step out of the shadows with my sap and conk erudite authors on the head, stick them in the back of a sedan, and take them “for a ride.”

high school students’ existences! But I absolutely love Moby-Dick. The style is like the ocean itself—undulating currents and crashing waves of narrative. Calms and storms and the occasional port. It’s also a whale of a story! And I love Ishmael from the start. Here’s part of page one:

was considered a comet of literary genius. He didn’t stop with short stories and novels. He also wrote plays and memoirs. He won (and famously turned down) the Pulitzer Prize. I think Saroyan’s My Name is Aram is one of the best collections of short stories ever put together. The first and last stories frame the entire work in a way that inspires pure wonder in me. My beloved high school English teacher, Mrs. Marjorie Bruce, introduced me to Saroyan.

…and to all a good night…

Reader Friday: Creating A Literary Monster

In 1816, during an unusually cold season caused by volcanic eruptions and circulating ash, 19-year-old Mary Shelley wrote a story about a monster as she and some friends struggled to stay warm. FRANKENSTEIN was born.

If you were to create a literary monster sprung from our own modern era of extreme and changing weather patterns, what would that monster be called? Can you describe it? (Be advised though, that SHARKNADO is already in the lexicon!) 🙂

Villains Don’t Have to be Evil

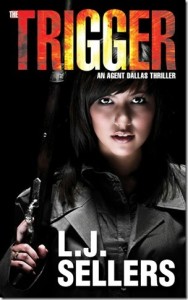

Guest Post from: L.J. Sellers, author of provocative mysteries & thrillers

Jordan Dane

@JordanDane

As my guest today, I have mystery thriller author L. J. Sellers writing about one of my favorite topics: Villains. LJ shares her thoughts and asks you to share your favorite villains at the end of her post. And be sure to check out the great giveaway contests below. Take it away, LJ!

The villains in thrillers are often extraordinary human beings. Super smart, physically indestructible, and/or incredibly powerful because of their money and influence. As a reader/consumer, those characters are fun for me too, especially in a visual medium where we get to watch them be amazing. But as an author, I like to write about antagonists who are everyday people—either caught up in extraordinary circumstances or so wedded to their own belief system and needs that they become delusional in how they see the world.

In my Detective Jackson stories, I rarely write from the POV of the antagonists. That would spoil the mystery! But in my thrillers, I get inside those characters’ heads so my readers can get to know them and fully understand their motives. I’ve heard readers complain about being subjected to the “bad guy POV,” but that’s typically when the antagonist is a serial killer or pure evil in some other way.

I share their pain. I don’t enjoy the serial-killer POV reading experience either. But when the villain in the story is a fully realized human being, who has good qualities as well as bad, and who’s suffered some type of victimization, and/or has great intentions, then I like see and feel all of that. And I think most readers do too.

In The Trigger, the antagonists are brothers, Spencer and Randall Clayton, founders of an isolated community of survivalists, or preppers, as they’re called today. As with most real-life isolationists/cult leaders, they are intelligent, successful professionals—with a vision for a better society. But these everyday characters decide to mold the world to suit their own objectives and see themselves as saviors—becoming villains in the process.

From a writer’s perspective, they were challenging to craft—likeable and believable enough for readers to identify with, yet edgy enough to be threatening on a grand scale. On the other hand, my protagonist Jamie Dallas, an FBI agent who specializes in undercover work, was such a joy to write that I’m launching a new series based on her.

The first book, The Trigger, releases January 1 in print and ebook formats, with an audiobook coming soon after. To celebrate the new series, the ebook will be on sale for $.99 on launch day. Everyone who buys a copy (print or digital) and forwards their Amazon receipt to lj@ljsellers.com will be entered to win a trip to Left Coast Crime 2015. For more details, check my website.

If that weren’t enough, I’m also giving away ten $50 Amazon gift certificates. So there’s a good chance of winning something. But the contest is only valid for January 1 purchases.

Who are your favorite villains? Supermen types? Everyday delusionals? Or something else?

L.J. Sellers writes the bestselling Detective Jackson mystery series—a two-time Readers Favorite Award winner—as well as provocative standalone thrillers. Her novels have been highly praised by reviewers, and her Jackson books are the highest-rated crime fiction on Amazon. L.J. resides in Eugene, Oregon where most of her novels are set and is an award-winning journalist who earned the Grand Neal. When not plotting murders, she enjoys standup comedy, cycling, social networking, and attending mystery conferences. She’s also been known to jump out of airplanes.

L.J. Sellers writes the bestselling Detective Jackson mystery series—a two-time Readers Favorite Award winner—as well as provocative standalone thrillers. Her novels have been highly praised by reviewers, and her Jackson books are the highest-rated crime fiction on Amazon. L.J. resides in Eugene, Oregon where most of her novels are set and is an award-winning journalist who earned the Grand Neal. When not plotting murders, she enjoys standup comedy, cycling, social networking, and attending mystery conferences. She’s also been known to jump out of airplanes.

Other social media links for LJ: Website, Blog, Facebook

Three Stages of Writing

In my view, story writing has three essential stages: Discovery, Writing, and Revision.

Discovery is the process by which you discover your story. Bits and pieces of character and plot swirl around in your subconscious before you put words to paper. Consider it creative energy at play rather than feeling guilty that you’re not being productive. This can be the break you need before starting the next novel. It’s time well spent to refill your creative pool and to gather ideas.

Doing a collage, watching movies, listening to music, working on a hobby, walking outdoors, or reading for pleasure are some of the ways you can stimulate your creativity. Cut out photos from magazines of celebrities who look like your characters and fill out your character development charts. Search for relevant articles to your storyline and sift through them. Thus begins your research. Often this prep time can take weeks or even a month or two. If you’re a seasoned writer, you’ll know how long you need. Be sure to factor this in when you determine your target goal of completion for your project.

When these ideas coalesce in your head and your characters begin to talk to you, you’re ready to start writing. This is when I sit down and write an entire synopsis. The synopsis acts as my writing guideline, so I always know where I’m going even if I don’t quite know how to get there. This still allows for the element of surprise. The plot may change as the story develops.

At this stage, set yourself a minimum daily quota. I have to write at least 5 pages a day or 25 pages a week. Beginning a book is the hardest task. It might take until the first third of the book for you to get to know your characters. Give yourself permission to write crap during this heated storytelling phase. Once the book is written, you can fix it. Just get those words down on paper and move forward until the draft is done.

When you finish the first round of storytelling, it’s a good idea to put your book aside so as to gain some distance from it. You’ll be better prepared for revisions with a fresh viewpoint. Use the time to plan your promo campaign, to jot down blog topic ideas, or to write reader discussion questions. When you find yourself eager to tackle the story again, move on to the next phase.

Now come the heavy revisions. This can get intense, because you need to keep a sense of the whole story in your head. You can’t stop, or you’ll lose your train of thought. But you also shouldn’t rush this process if you want to produce what editors call a “clean” copy.

When you set deadlines, be sure to allow a month or so for revisions, because you’ll need to do several read-throughs. My first round of revisions focuses on line editing. Then I’ll read through for smoothness and consistency. The final reading is to catch any remaining errors, typos, or repetitions. You can run your material through one of the online editors like Smart-Edit software or Pro Writing Aid.

I guarantee you’ll always find things to correct, but at some point you’ll be too close to the material to see straight or too sick of the project to work on it any more. Then the book is ready to submit. But don’t worry, likely you’ll have a chance to fix things again when you hear from your editor.

Send it off, clean up your desk, file away your mounds of papers. By now you’re thinking about the next book and are getting ready to start the process anew. Force yourself away from the office and take some time off. You’ll return with fresh ideas and renewed energy.

Now I have to quit procrastinating and get back to the writing stage. After being away for a week, it’s hard to get back in the groove.

Is your book a Christmas sweater?

Speaking of King, here’s what he says in his book “On Writing”:

“Description begins with visualization of what it is you want the reader to experience. It ends with your translating what you see in your mind into words on the page. It is far from easy. We’ve all heard someone say, ‘Man, it was so great (or horrible/ strange /funny)…I just can’t describe it!’ If you want to be a successful writer, you must be able to describe it, and in a way that will cause your reader to prickle with recognition. If you can do this well, you will be paid for your labors. If you can’t, you’re going to collect a lot of rejection slips.”

“Prickle with recognition.” Isn’t that a great way to put it?

“Description is a learned skill, one of the reasons why you cannot succeed unless you read a lot and write a lot. It is not a question of how-to, you see; it is also a question of how much to. Reading will help you answer how much, and only reams of writing will help you with the how. You can only learn by doing. “

I’ll leave you with one final fashion icon as metaphor. If you try hard, you can get better at this. If she could go from this:

To this:

So can you.

Using Thought-Reactions to Add Attitude & Immediacy

by Jodie Renner, editor & author

by Jodie Renner, editor & author

In my editing and blog posts, I often suggest techniques for bringing characters and the scene to life on the page. A big one I advise over and over is to show the protagonist’s immediate emotional, physical, and/or thought reactions to anything significant that has just happened. This glimpse into the POV character’s real feelings and thoughts increases readers’ emotional engagement, which keeps them eagerly reading. (See Show Your Characters’ Reactions to Bring Them Alive)

Showing your character’s immediate thought-reactions frequently is a great way to let the readers in on what your character is really thinking about what’s going on, how they’re reacting inside, often in contrast to what they’re saying or how they’re acting outwardly. And it helps reveal their personality.

Here are some examples of brief, immediate thought-reactions:

|

| A scene in Breaking Bad |

No!

Damn.

What?

In your dreams.

What the hell?

Give me a break!

These direct thoughts, the equivalent of direct speech in quotation marks, are silent, inner words the character can’t or doesn’t want to reveal. It’s most effective to italicize these quick, brief thought-reactions, both for emphasis and to show that it’s a direct thought, like the character talking to herself, not the slightly removed indirect thought.

Here are a few examples of indirect thoughts vs. the closer-in, higher-impact direct thoughts:

Indirect: She’d had enough. She really wanted to leave.

Indirect: She’d had enough. She really wanted to leave.

Direct speech: “I’ve had enough. I’m heading out.”

Direct thought: This sucks! I’m outta here.

(Or whatever. More personal, more unique voice, more attitude, less social veneer.)

Use present tense for direct thoughts.

If your story is in past tense, as most novels are, narration, indirect speech and thoughts will be in past tense, too. But it’s important to put direct, quoted speech and direct, italicized thoughts in present tense, and first-person (or sometimes second person), as they are the exact words the character is thinking.

Direct thoughts = internal dialogue.

Note: Never use quotation marks for thoughts. Quotation marks are for words spoken out loud.

A few more examples:

Indirect thought: He wondered where she was.

Direct speech (dialogue): “Where is she?” he asked.

Direct thought: Where is she? Or: Where the hell is she, anyway?

Note how the italics take the place of quotation marks when it’s a direct thought, the character talking to himself. Also, the italics indicate direct thoughts, so no need to add “he thought” or “she thought.”

Indirect speech: She asked us what was going on.

Indirect thought: She wondered what was going on.

Direct speech: “What’s going on here?” she asked.

Direct thought-reaction: What on earth is going on?

(Or whatever, according to the voice of the POV character.)

To me, using these direct thought-reactions brings the character more to life by showing their innermost, uncensored thoughts and impulses.

In these cases, italics for thoughts take the place of the quotation marks that would be used if the words were spoken out loud. But I advise against putting several long thoughts in a row into italics. In fact, do we even think in complete sentences arranged in logical order to create paragraphs? I don’t think so. Thoughts are often disjointed fragments, as is casual dialogue.

Since italics are also used for emphasis, be sure not to overdo them, or they’ll lose their power.

But do use italics for those immediate thought-reactions, the equivalent of saying out loud, “What!” or “No way!” or “You wish.” Or “I don’t think so.” Or “Yeah, right.” Or “Great.” Or “Perfect.” Or “Oh my god.” Only, for thoughts, take off the quotation marks, of course, so you’ll write: What! or No way, etc.

To me, italics used in this way indicate a fast, sudden break in the social veneer, a revelation or peek into the psyche of the thinker.

So try to insert direct thought-reactions where appropriate to effectively show your character’s immediate internal reactions to events.

But don’t italicize indirect thoughts.

To me, italicizing indirect thoughts (in third-person, past tense) would be the same as putting quotation marks around indirect speech, like: He said, “He wished he could come, too.” (Should be: He said, “I wish I could come, too.”)

So don’t italicize phrases like: Why were they looking for her? She had to find a place to hide!

(“her” and “she” refer to the person thinking.) Keep it in normal font, or change it to a direct thought and italicize:

Why are they looking for me? Where can I hide?

EXAMPLES FROM BESTSELLERS:

Some bestselling authors use a lot of italicized thought-reactions, while others just use them sparingly or not at all. It seems to be a growing trend, though, and I think it’s a great technique for highlighting the character’s inner emotional reactions effectively, directly, and in the fewest possible words.

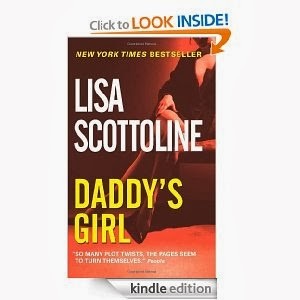

Lisa Scottoline, for example, uses italicized brief thought-reactions a lot in her novels. They provide a quick peek into the character’s immediate thoughts, without a lot of explaining. Like in Daddy’s Girl:

The heroine, Natalie, has a small cut on her face, and her father, on the phone, asks which hospital

she went to. She says she didn’t need to, “It’s just a little cut.”

“On your face, no cut is too little. You don’t want a scar. You’re not one of the boys.”

Oh please. “Dad, it won’t scar.”

Later, a good-looking guy, Angus, makes a suggestion about lunch while they’re working.

Did he just ask me out?

Later, as they’re working together, Angus tries to protect her, but she isn’t having any of it. The thought-reaction shows the contrast between how she’s really feeling and how she wants him to think she’s going along with his plans.

“I’ll get you out of here in the morning, and you’ll be safe.”

No way. “Okay, you’ve convinced me.”

No way. “Okay, you’ve convinced me.”

Andrew Gross uses frequent thought-reactions in italics very effectively in his riveting thriller, Don’t Look Twice. Here’s one brief example:

A chill ran down her spine. … Don’t let him see you. Get the hell out of here, the tremor said.

And Dean Koontz uses this technique from time to time in his novel Intensity. For example:

Chyna is hesitating about opening a door, then decides to throw caution to the wind:

Screw it.

Screw it.

She put her hand on the knob, turned it cautiously, and…

Then later:

He was coming forward, leisurely covering the same territory over which Chyna had just scuttled.

What the hell is he doing?

She wanted to take the photograph but didn’t dare. She put it on the floor where she’d found it.

Note that these intensified thoughts are often at the beginning of a paragraph or set off in their own line, for emphasis. Or sometimes they’re at the end of a paragraph, to leave us with something to think about, as in later in the same book.

Lee Child’s The Affair has lots of examples of Jack Reacher’s critical thoughts in italics. Here’s one of many I could have chosen:

He asked “Was I on your list of things that might crawl out from under a rock?”

He asked “Was I on your list of things that might crawl out from under a rock?”

You were the list, I thought.

He said, “Was I?”

“No,” I lied.

(Not to nit-pick with a huge bestselling author, but in my opinion, neither the “I thought” or the “I lied” are necessary above.)

Lee Child also uses this technique a lot in The Hard Way, especially to show Jack Reacher’s mind busily working away while he’s talking to or watching someone, or to emphasize the importance of a bit of info he’s just learned.

David Baldacci uses this technique frequently in Hell’s Corner to show the direct thoughts of his

David Baldacci uses this technique frequently in Hell’s Corner to show the direct thoughts of his

protagonist, Oliver Stone. Here’s one example:

Burn in hell, Carter, thought Stone as the door closed behind him.

And I’ll see you when I get there.

Brenda Novak, in her romantic suspense, In Close, uses italicized thoughts to show the contrast between what the character, Claire, is saying and what she’s really thinking:

“Maybe I could get back to you in the morning after I’ve…I’ve had some sleep.” And a chance to prepare myself for what you might say….

Even TKZ’s James Scott Bell uses this technique in his delightful novellette, Force of Habit. The spunky, rebellious Sister J, a former actress and trained martial arts expert, is being confronted by someone obnoxious who has recognized her. Her internal dialogue shows her (unsuccessful) attempt at calming herself.

Even TKZ’s James Scott Bell uses this technique in his delightful novellette, Force of Habit. The spunky, rebellious Sister J, a former actress and trained martial arts expert, is being confronted by someone obnoxious who has recognized her. Her internal dialogue shows her (unsuccessful) attempt at calming herself.

“Can you still kick butt?”

She could all right, and she felt like kicking something right now. His shin, if not the wall. Think of St. Francis, she told herself. Think of birds and flowers…

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.

First Be a Storyteller

I was a student in one of the best film studies programs in the country during the golden age of American movies. The 1970s saw an explosion of great independent films and directors, many of whom were picked up by major studios. Up at U.C. Santa Barbara, our intimate band of film majors got to sit around talking with exciting new directors like Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Lina Wertmuller and Alan Rudolph.

Wyler’s films have won twice the number of Academy Awards as any other director’s. Of the 127 nominations, half of them were in the Best Picture, Director and Actor categories. No less a light than Bette Davis credited Wyler with deepening her art and turning her into a major star.

Very Young Adult

By Mark Alpert