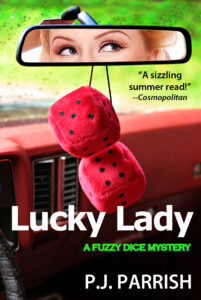

By PJ Parrish

We’re off to sunny Arizona today for our First Pager, and into the shady heart of a bad girl. Thank you, writer, for letting us read your submission today and, as always, learn along with you. And this has left me with a yen for a blue margarita. Cheers!

Cartel Queen Veronica Valdez

CHAPTER 1

The Four Seasons Resort Scottsdale

Onyx Bar

Monday, October 20, 2019

“Hurl! Loser!”

Eight twenty-something male golfers sat on the patio crushing beers and trading insults.

Veronica Valdez glared at the window. I didn’t come here for party-till-you-puke feral males. She sat at a high-top table and ordered a blue margarita.

An ASU freshman, Veronica’s fake driver’s license identified her as twenty-two year old Shirley Smith. Designer clothes and accessories gave the impression of a sophisticated professional.

With a smile as fake as a TV game-show host, a man appeared. “I’m Tommy Thompson. May I join you?”

“Of course, I’m Shirley Smith. What’s your first name?”

“Orville,” he whispered.

“Orville, this will be our secret.”

Swaggered over here. Has a room. Luxury watch.

Veronica nudged her scarlet Valentino tote bag off the table, and Thompson retrieved it. “Thanks, the least I can do is buy you a blue margarita.”

“Okay, but they’re on me.”

On you? You’ll forget your name when we’re finished.

Their drinks arrive minutes later.

“The Blue Curacao liqueur gives the margarita its color.” I won’t tell him it hides the Roofie’s blue tint.

They played where-are-you-from and what-do-you-do, and during an awkward lull Veronica’s left hand pulled Thompson’s head close, and the snogging began. She circled her tongue inside his mouth, dropped her left hand, and slid it under his crotch. Still kissing, she squeezed his crotch and when he whimpered, her right hand dropped a tasteless pale-green and blue-speckled, fast-dissolving roofie tablet into his blue margarita.

“Bet you can’t drain yours, Tommy.” If he’s trying to get into my pants, he’ll over-compensate. That’s what men do. Thompson finished his blue margarita in three gulps.

The bartender’s generous pour combined with an anesthetic dose of Rohypnol affected Thompson. “Thizz marga uh uh is thong. Not too thong for me. Hah!” Now you’re on your ass. Right where I want you, Orville.

Veronica paid the check and walked a babbling, unsteady Thompson to his room where she undressed him, and tucked him in bed. After checking his pulse and respiration, she left with his $30,000 White Gold Rolex GMT Master II along with his wallet, iPhone, and $789. She’d keep the cash and sell the watch, credit cards, iPhone, and driver’s license on the dark web.

Behind the wheel of her truck, Veronica rubbed herself with the watch until she moaned and shivered.

_____________________________

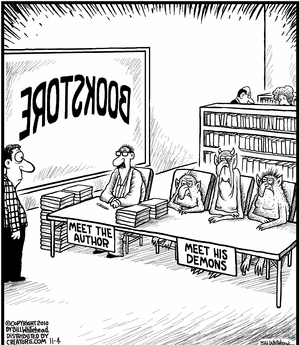

I’m back. Well, looks like we’re dealing with a femme fatale here. Which gives us a chance to talk about opening your story with the antagonist. Is it a good idea or just a cliche? Should you give that first spotlight to the villain or introduce your hero first? And, to make it more complicated, what if your protagonist is also an antagonist? Books and movies are rife with successful examples of this hybrid: Darkly Dreaming Dexter, American Psycho, A Clockwork Orange, Interview With the Vampire, and one of my favorite books-cum-movies The Talented Mr. Ripley.

So who do you shove out onto the stage first?

In movies, this is called the Establishing Character Moment. Often it’s given to the protag, but sometimes, the villain goes first. I was watching Dirty Harry the other night, and of course, I was analyzing the heck out of it. It’s about a serial killer called Scorpio. The opening is terrific. (A lot of credit needs to go to cinematographer Bruce Surtees, whose seminal chiaroscuro style was artful-creepy). The scene opens with the sound of church bells. Then we get a shot of a pretty girl, sighted through a rifle scope, swimming in a rooftop pool. The shot pulls out to show the shooter taking aim…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nDXdhA-Z3-o

Indulge me a moment more while we talk about how Darkly Dreaming Dexter opens. First, we get a brief orgasmic ode to the moon then comes this graph:

I had been waiting and watching the priest for five weeks now. The need had been prickling and teasing prodding at me to find one, the next one, find this priest. Three weeks I had known he was it, the next one, we belonged to the Dark Passenger, he and I together. And that three weeks I had been fighting the pressure, the growing Need rising in me like a great wave that roars up and over the beach and does not recede, only swells with every tick of the bright night’s clock.

The bad guy as protag! One of my favorite books from high school was John Fowles’s The Collector, much of it written from the abductor’s POV. Here’s the opening graph:

When she was home from her boarding-school I used to see her almost every day sometimes, because their house was right opposite the Town Hall Annex. She and her younger sister used to go in and out a lot, often with young men, which of course I didn’t like. When I had a free moment from the files and ledgers I stood by the window and used to look down over the road over the frosting and sometimes I’d see her. In the evening I marked it in my observations diary, at first with X, and then when I knew her name with M.I saw her several times outside too. I stood right behind her once in a queue at the public library down Crossfield Street. She didn’t look once at me, but I watched the back of her head and her hair in a long pigtail. It was very pale, silky, like Burnet cocoons. All in one pigtail coming down almost to her waist, sometimes in front, sometimes at the back. Sometimes she wore it up. Only once, before she came to be my guest here, did I have the privilege to see her with it loose, and it took my breath away it was so beautiful, like a mermaid.

I am pretty sure this paragraph was swimming around in my subconsciousness when I wrote my stand-alone serial killer The Killing Song, which opens with the murderer admiring his next victim as she sits in a concert in Paris’s Sainte Chapelle. So…if you’re going to open with the bad guy, you better be able to get into your killer’s skin, no matter how warty it is.

Which brings us, at last, to our submission today. (Thanks for your patience, writer, but I really needed to make a point about opening with bad guys first).

Now, in such a short sample, we can’t be sure Veronica is our villain. She could be the protagonist dressed up in anti-heroine Prada. Given the title, that’s my guess. Maybe the writer can weigh in with some insight? But we can still comment on the effectiveness of this opening in catching our attention and maybe what can be done to improve things. Some general observations first:

There’s some potential here. But I really think this writer needs to slow things down. Here is what happens, just in the plot-events: We’re in a bar where we meet the main character Veronica. She is clearly there to prey on someone, complete with fake ID and fancy togs. She hones in on a victim and they have drinks, small talk, and she sort of seduces him. She slips him a roofie, and he gets woozy and can barely talk. Somehow, they get upstairs to his room where she undresses him and tucks him into bed. She steals his watch, wallet, phone and cash. She goes downstairs and out to the parking lot to her truck. She masturbates with his Rolex.

All this in…385 words. Way too fast.

What doesn’t happen is: establishment of location. (other than a superfluous tagline); any description of surroundings (and we’re in a beautiful desert luxury hotel!); what anyone looks like or sounds like (other a fakey-smile and roofie-drunk slurring); why Veronica is there, outside of ripping off men; basic choreography of moving the characters around in space. How do they get up to his room when he’s half-passed out? How does she get to her truck? And there is not even a hint of character motivation or insight.

That last one is a biggie. Because if you are dealing with an antagonist/protagonist or an anti-heroine, you darn well better be prepared to plumb the depths of her deepest needs, wants, fears and yes, loves. And that begins at the beginning.

If the antagonist is important enough to get her own point of view, she ought to have goals and motives driving her — same as any other character, and we need to see the beginnings of this layering in the first chapter in which she appears. One trick to writing a solid bad guy is to make him the hero of his own story. (I think this is a James credo). Few people actually consider themselves evil or bad, so even if Veronica has an iota of conscience, she will at least rationalize it.

Right now, Veronica is a cipher. The fact she’s female doesn’t make her any less a cliche in today’s crime fiction. When you find a way to make her feel like a real woman with real problems, readers will want to follow her — even if she’s a bad girl. I suggest the writer read T. Jefferson Parker’s L.A. Outlaws. I It’s about a rookie cop who gets caught up in an affair with a Robin-Hoodish bad girl. Here’s the opening of Chapter 1, written from the female antagonist’s POV:

Here’s the deal: I am a direct descendent of the outlaw Joaquin Murrieta. He was a kickass horseman, gambler, and marksman. He stole the best horses, robbed rich anglos at gunpoint. He loved women and seduced more than a few during his twenty-three years. Some of his money went to the poor, but to be truthful most of it he spent on whiskey, guns, expensive tailored clothes, and on the women and children he left behind.

I got Joaquin Murrieta’s good looks. I got his courage and sense of justice for the poor. I got his contempt for the rich and powerful. I got his love of seduction. Like Joaquin used to, I love a good, clean armed robbery. I steal beautiful cars instead of beautiful horses.

Right now I’m about to stick up a west-side dude for twenty-four thousand dollars in cash. He won’t be happy, but he’ll turn it over.

And I’ll be richer and more famous than I already am.

My name is Allison Murrieta.

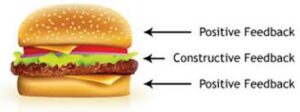

So my main advice, dear writer, is to slow down. All the action you cover in 385 words would make a good entire first chapter. And that’s not even accounting for adding better character development. Even poor Orville merits a physical description. Beyond this, you have some problems with simple confusion. Let’s do a line edit and clear up some of that up.

The Four Seasons Resort Scottsdale

Onyx Bar

Monday, October 20, 2019

Generally, you should use this device for big complex plots that ricochet around in time and place. All this info could be — should be — woven into the narrative. (ie: The Onyx Bar was almost deserted, except for a quartet of young guys just coming in from the 18th green. Their cleats clacked on the wood floor and their drunken laughter echoed off the adobe walls. Veronica watched them for a moment then swiveled on her bar stool to look out huge windows. The sun was just dipping below Pinnacle Peak. God, she loved The Four Seasons. The best resort in Scottsdale. Best views, best food, and best place for hunting men who weren’t too smart.

That’s bad but you get the idea. SHOW us where we are with choice details. Don’t TELL us in a wooden tagline.

“Hurl! Loser!” Do you really want to use up your precious first line on a nameless frat-boy who has no bearing on anything? Put the spotlight on Veronica. She is there for one thing — to find a male mark. Make her ACTIVE rather than reactive to the barf boys.

Eight twenty-something male golfers sat on the patio crushing beers and trading insults.

Veronica Valdez glared at the window. I didn’t come here for party-till-you-puke feral males. She sat Was she standing and just now sat down or already sitting? at a high-top table and ordered a blue margarita.

An ASU freshman, Veronica’s fake driver’s license identified her as twenty-two year old Shirley Smith. Another example of TELLING instead of showing. Turn it into action, something like this:

When the waitress came over, Veronica said, “I’ll have a blue margarita.”

The waitress’s eyes narrowed. “Can I see some ID?”

Veronica pulled out her wallet and flipped it open to her license. She stayed cool, knowing the stupid girl couldn’t tell it was fake. Behind the license was her Arizona State student ID. That was real. As real as her Valentino Hobo Bag, Chanel boucel jacket and her Louboutin booties.

Designer clothes and accessories gave the impression of a sophisticated professional. See above blue comment. SHOW us with telling details that she presents a sophisticated front. You also might be able to slip in hints of her physical appearance. The blonde hair wasn’t real, but the breasts were. You can do something with this real vs fake thing. Which might end up standing for something larger symbolically about this woman. Plumb her depths.

With a smile as fake as a TV game-show host, a man appeared. From where? Also, she is a predator so wouldn’t she notice him first? She’s trolling for a mark, so make her ACTIVE. What does he look like? A Chiclet smile isn’t enough. SHOW us through her eyes. “I’m Tommy Thompson. May I join you?” Do you realize all your names are alliterative? I’d change that.

“Of course, I’m Shirley Smith. What’s your first name?” I don’t understand. He just told her his name was Tommy.

“Orville,” he whispered.

“Orville, this will be our secret.” Again, confusing. What is the secret?

Swaggered over here. Has a room. Luxury watch. Tell us here what kind, not later. And how does she know he has a room? Maybe she sees him slip a key into his jacket before he comes over? She’s the predator here, so make her smarter. Has she done this before? Here’s a good opportunity to slip in a hint of backstory. She needs it. And be careful that she’s not a regular here or management would note. Which can also be a good backstory note, something like:

She knew all the best hotel bars, from San Francisco to Savannah. The Onyx had always been her favorite, though she was careful not to show up too often. Bartenders noticed women who drank alone. They remembered. And she couldn’t risk that.

Veronica nudged her scarlet Valentino tote bag off the table, and Thompson retrieved it. Confusing. Did he catch her bag as it fell off the table? “Thanks, the least I can do is buy you a blue margarita.” She already ordered one. Perhaps it’s more interesting to have him ask what’s that blue thing she’s drinking? Also, your dialogue here is a little anemic. Make it work harder. Make it SAY something about Veronica. Maybe he makes some lame pick-up remark like, “What? You ordered that because it matches your eyes?” Which gets you a way of slipping in what she looks like. Or maybe she wears blue contacts? I suggest you go back and read James’s post on how Telling Details can enliven your story.

“Okay, but they’re on me.”

On you? You’ll forget your name when we’re finished.

Their drinks arrive minutes later. Whoa. You need to slow down here. You just had these two meet, so you really can’t jump ahead with an empty time-bridge like this. What do they do? What did they say? You’re missing chances to flesh out your set-up and your main character.

“The Blue Curacao liqueur gives the margarita its color.” I won’t tell him it hides the Roofie’s blue tint. A non sequitur — of course she wouldn’t tell him she’s drugging his drink. The italics tells us we are in her head, and because the sentences are joined in one graph, we assume she said the thing about the Curacao? But it’s unclear.

They played where-are-you-from and what-do-you-do, and during an awkward lull Veronica’s left hand pulled Thompson’s head close, Because this “seduction” is so rushed, I’m not buying this action. You need to set it up better to make it believable. Also, they are sitting at a high-top table in full view of a classy bar, so this is borderline unbelievable. and the snogging Why use British slang for making out? began. She circled her tongue inside his mouth, dropped her left hand, and slid it under his crotch. Under? Still kissing, she squeezed his crotch and when he whimpered, her right hand dropped a tasteless pale-green and blue-speckled, fast-dissolving roofie tablet into his blue margarita drink.. Here is an example of wrong details. Just describe the salient action. She dropped the roofie into his glass. It dissolved before he had time to open his eyes.

“Bet you can’t drain yours, Tommy.” If he’s trying to get into my pants, he’ll over-compensate. That’s what men do. You need a new graph here: Thompson finished his blue margarita drink in three gulps. The bartender’s generous pour combined with anesthetic dose of the Rohypnol affected Thompson. Again, why tell us when you can show us? New graph needed for dialogue “Thizz marga uh uh is thong. Not too thong for me. Hah!” New graph needed because you change to her thoughts. Now you’re on your ass. Did he fall off the chair? Right where I want you, Orville.

Re: Roofies. I did a lot of research on this drug for one of my own books, and you need to be careful in your description here. They are a depressant. Depending on the dose, it takes a good 20 to 60 minutes for them to take affect, maybe more for a man. Also, because of date rape abuse, they are no longer legally available in U.S. Maybe she got it in Mexico? Again, this could be a telling detail about your character.

Veronica paid the check and walked a babbling, unsteady Thompson to his room where she undressed him, and tucked him in bed. You really need to slow your action down here. The roofie would make him almost unable to walk. Is he large? Is she small? Was he hard to maneuver? No one noticed this in the bar? How did she get his key card? They don’t have room numbers on them so how does she know where the room is? Sorry if this sounds niggling, but you can’t just gloss over details like this. After checking his pulse and respiration, she left with his $30,000 White Gold Rolex GMT Master II along with his wallet, iPhone, and $789. She’d keep the cash and sell the watch, credit cards, iPhone, and driver’s license on the dark web.

I have a question about iPhones that is above my pay grade. I know they are big targets of thieves who resell them, but there are also ways to guard against that and they can be traced. This makes me wonder — what kind of criminal is Veronica? The scenario here describes a petty theft because she’s not going to make a fortune reselling this stuff. Is she up to bigger things — like she’s part of phishing scheme? Then keeping the iPhone makes sense. This goes to my point about the need to start layering in some backstory here. Because a college girl drugging older guys in bars just to steal their watches and wallets isn’t very interesting. The stakes need to be bigger, I think.

Then…out to the parking lot we go. Slow down! One sec we’re in a hotel room, next in a car. Whiplash!

Behind the wheel of her truck, rusty Ford flatbed? Platinum Silverado? Vintage Jeep? Veronica rubbed herself with the watch until she moaned and shivered. Well, that’s quite an image, but again, slow down! Nobody likes to be rushed in a seduction, even if it’s a solo act. She gets in the truck. Give her a thought or two. Have her watch the sun go down. Maybe she thinks about poor Orville “roached-out” (that’s slang for being high on roofies) up in his fancy room (which you never described). Maybe she takes out his wallet and sees a photo of the kids. Give us something! Humanize these characters! And then, she leans back in the seat and gazes out at the beautiful Scottsdale sunset. It’s been good day at the “office.” She reaches into the Hobo bag and pulls out the watch. She admires it. She admires herself. She thinks something, anything! Okay, maybe we can go with the sex thing then, but it would be better with some kind of human context. Even if her heart is black, you have to show it to us because as I said in the general comments, a villain has to be believable and multi-dimensional. She’s as blank as a blow-up doll right now.

A final thought. Roofies are called “the forget-me-pill.” Boy, I’d sure do something with that given your scenario. Every chapter needs a good kicker. Poor Orville will forget, given the lasting effects of roofies. But who’s really trying to “forget-me” here? Maybe your bad girl herself? Look for depths to plumb in your characters, especially your villains.

That’s about it. If this sounds harsh, please know, dear writer, I am not doing this to discourage you. I think you’re onto something here, and the spareness of your writing shows some talent. (though I still think it’s too spare). You’ve got something potent going here but I’m not sure you know what’s truly inside Veronica. I want to know more about her. Strangely enough, I even want to like her because there’s nothing like a dame gone wrong who maybe, just maybe, finds a way to right herself. I really encourage you to check out T. Jeff’s L.A. Outlaws. Reading good writers helps us find our way. And don’t give up. I’m hard on you because this has potential.

Thanks for submitting!

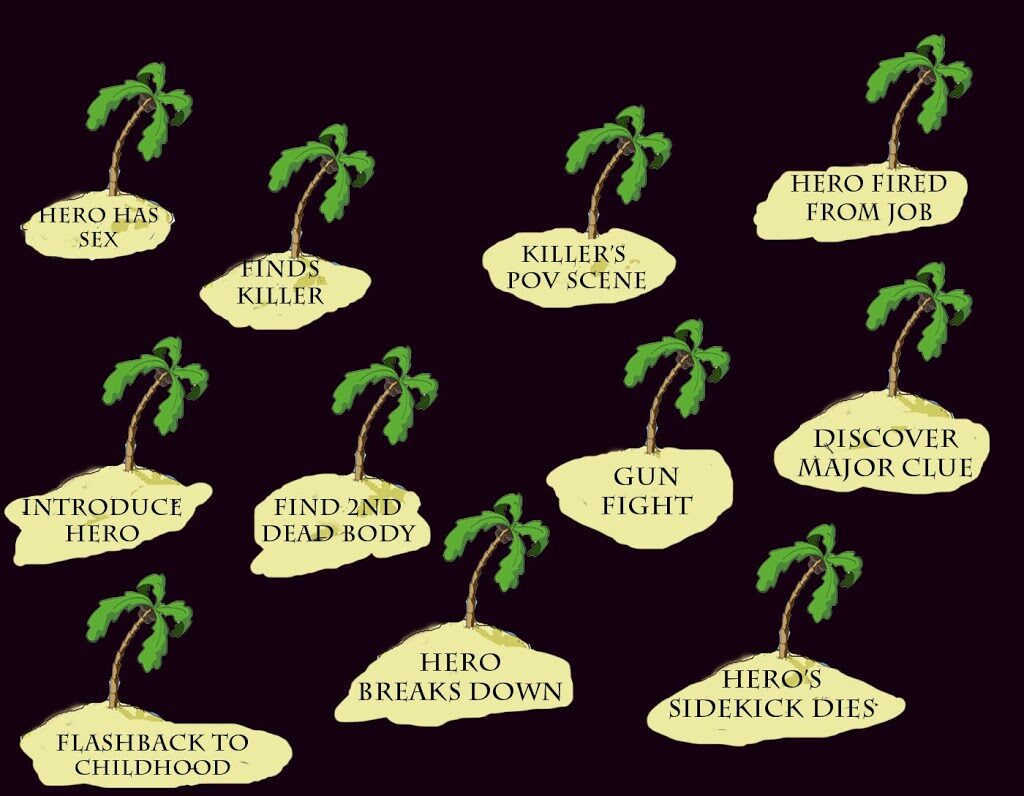

Maybe it’s helpful to think of each chapter as a dramatic island. (I wrote a whole blog about this a couple years back). Then build bridges (transitions) between them. Or think of each chapter as a mini short-story. Each chapter, ideally, has its own dramatic arc — a beginning to pull the reader in, a middle with meat, and a kicker ending that makes the reader want to turn the page.

Maybe it’s helpful to think of each chapter as a dramatic island. (I wrote a whole blog about this a couple years back). Then build bridges (transitions) between them. Or think of each chapter as a mini short-story. Each chapter, ideally, has its own dramatic arc — a beginning to pull the reader in, a middle with meat, and a kicker ending that makes the reader want to turn the page.