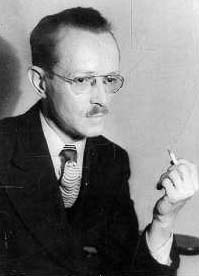

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

In recent years, when I’ve done live teaching, I’ve noticed something. The audience keeps getting younger.

In recent years, when I’ve done live teaching, I’ve noticed something. The audience keeps getting younger.

How’s that happen?

And I’ve noticed something else which astonishes me. More and more of these aspiring writers have never seen Casablanca! Or lots of the old classics.

Let me remove my ear horn for a moment and declare that when I was their age, everyone who wanted to write—indeed, most everyone at all with a streak of the artist in them—knew classic movies from the “golden age” of American cinema.

Yeah, I know, it’s generational. When I was a lad, we had three networks and a few local channels. We didn’t have 24/7 stimuli pounding our eyes and ears. We knew the richness of movie history—the poetry of Ford, the heart of Capra, the pure genius of Welles, the mean streets of noir. Astaire-Rogers. Tracy-Hepburn. Bogart-Bacall.

I’ve heard on more than one occasion from someone in their 20s or 30s that they just don’t like black-and-white films. They would rather watch full-color TikTok videos of dancing parrots and people slipping on ice than the greatest movies ever made. It’s a pity, because writers can learn so much from past masters of film.

Case in point is Stagecoach (1939), directed by John Ford.

Case in point is Stagecoach (1939), directed by John Ford.

This is the movie that turned John Wayne into John Wayne. In 1926, when he was playing football at USC, Wayne (then known by his given name, Marion Morrison) got summer work moving props for the studios. One day John Ford walked by. Knowing Wayne was a football player, as Ford himself had been, the director challenged Wayne to try and knock him down. Wayne, not knowing how important this guy was, did so. Ford took an immediate shine to the strapping lad.

For most of the 1930s, Wayne starred in low-budget, forgettable Westerns produced on “Poverty Row.” But when it came time to cast the central character of the Ringo Kid in Stagecoach, Ford fought to cast Wayne. The rest, as they say, is history.

While Stagecoach has many familiar tropes of the traditional Western—Apache attack, the cavalry, bars, a climactic gunfight—most of the movie is a tight drama about nine people on a stagecoach journey across the prairie to a town called Lordsburg. How did that plot birth a classic?

Orchestration

First and foremost, all the characters are distinct and contrasting. I call this orchestration. Just like different instruments blending together create a beautiful symphony, so disparate characters make for compelling drama (and, I might add, comedy).

Played by some of the best character actors of the day, we have:

- A drunken doctor (Thomas Mitchell, who won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar)

- A nervous little whiskey drummer (Donald Meek)

- A sly, Southern gambler (John Carradine, based on Doc Holliday)

- A woman of ill repute (Claire Trevor)

- A pregnant wife trying to get to her soldier husband (Louise Platt)

- A goofy driver (Andy Devine)

- A bank embezzler (Berton Churchill)

- A sheriff (George Bancroft)

John Wayne as the Ringo Kid

Along the way they pick up Ringo (with a great visual intro of Wayne spinning his Winchester, an image for the ages). The sheriff places him under arrest.

Lesson: A great novel orchestrates its cast. Even the minor characters. This enables endless possibilities for conflict and tension. Take time with this when planning (or pantsing), as it will pay big dividends as you unfold your story.

Style

Ford was one of the great visual artists of cinema. Parts of Stagecoach were filmed in what became Ford’s favorite outdoor venue—Monument Valley. His use of horizon and sky is unmatched (see also The Searchers). He once said, “Monument Valley is the place where God placed the West.”

His interiors are just as striking. His use of light and shadow is masterful in Stagecoach because it’s in black-and-white.

Lesson: I liken this to a writer’s style. We’ve had lots of discussions about this. Is it worth it to hunt for the right word? The right sound? Or in this age of pervasive sameness, now churned out by bots, is such care merely slowing us down in our pursuit of prolificity and page reads?

You have to decide for yourself. John Ford could have churned out Westerns every few weeks, like the Poverty Row guys. He could have added mere content to the glut. Instead, he made his movies unforgettable, shot by shot.

This is where voice comes in. Take some time to develop this “secret power.” It will lift your work above the lifeless ubiquity of botness that marks our era.

Stretching the Tension

The stagecoach journey is leading up to Ringo finding Luke Plummer and his brothers in Lordsburg, to avenge the murder of his father and brother. The last part of the movie is the countdown to the gunfight.

Ford doesn’t rush it. He begins with Luke and his boys in a saloon, hearing that Ringo is in town. Doc Boone (Mitchell) has a tense encounter with Plummer, warning him that if he takes the shotgun just handed to him, he’ll have him indicted for murder. The moment stretches. Will Plummer gun down the doctor? Smash him in the face? This silent moment lasts nearly seconds. Finally, with a wry smile, Plummer tosses the shotgun on the bar top. “We’ll tend to you later,” he says. When he and his two brothers walk out, Doc takes a swift drink. “Don’t ever let me do that again,” he says to the barkeep.

Outside, a woman on the balcony tosses Plummer a rifle.

We cut to the newspaper office. The editor rushes in and tells his typesetter, “Kill that story about the Republican convention and take this down. The Ringo Kid was killed on Main Street in Lordsburg tonight! Among the additional dead were…leave that blank for a spell.”

“I didn’t hear any shooting,” the typesetter says.

“You will.”

Step by step, the Plummer boys head for the showdown. Ringo, spurs jingling (another trope), comes up the other end of the street.

Lesson: When you’ve created a good, tight scene with great tension, don’t cut it off too soon. Stretch that tension. Read the opening of Koontz’s Whispers, which takes 17 pages to describe a rapist stalking a woman in a house. Study the last fifty pages of a Jonathan Grave thriller. Stretch tension as far as you can in a first draft. You can always cut back when you edit. But I think you’ll find you won’t want to.

Twist in the Tail

Usually in a Western, the climactic gun battle ends the movie. The townspeople gather around the hero and his woman embraces him; or the lone hero mounts his horse and quietly rides into the sunset as THE END appears.

In Stagecoach, there’s an added beat, because Ringo is still under arrest and headed for prison…or is he?

I’m not going to tell you because I want you to watch the movie!

Suffice to say it’s perfect.

A twist in the tail is a super satisfying way to end a story. And to bring us back to Casablanca (watch it now!), that movie has perhaps the most famous tail twist of all time, the one that ends with, “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Lesson: How do you come up with a great twist in the tail? You write two, three, of even more possible endings. Choose the best one for your actual ending, then use the next best for your twist.

Here’s a further hint. A great ending often involves sacrifice; the hero offers his life (Casablanca) for a greater good. But the twist gives him a reward, a new beginning, another chance at life. It’s right there in Stagecoach, too.

As film critic Roger Ebert said, “Stagecoach holds our attention effortlessly and is paced with the elegance of a symphony. Ford doesn’t squander his action and violence in an attempt to whore for those with short attention spans, but tells a story.”

Wouldn’t you like to tell a story like that?

Comments welcome.