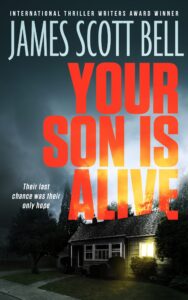

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Recently one of our regulars, RLM Cooper, posted a comment, to wit:

Recently one of our regulars, RLM Cooper, posted a comment, to wit:

What I’d like to know is not how to avoid critics, but how to get your book noticed in the first place. My book has great reviews (all handful of them) but Amazon makes it nearly impossible to find even when you key in the exact title of it. Unless you know the author and the book title, you are toast. I’ve tried advertising (on a small scale – I’m a writer, not a billionaire). I’ve tried having someone “promote” my book by placing posts on their book promo site with “thousands of followers.” And each day, new books are published and mine sinks down a bit in the Amazon ratings….You all know how much work, sweat, time, tears, effort, love goes into your work. How do you cope when almost no one notices? … How do you keep going when nothing seems to help? … I’m becoming discouraged even with the great reviews my book has gotten. Is it worth it to keep on keeping on?

To which our own Steve Hooley offered foundational advice: “Don’t give up, RLM. Remember PERSEVERANCE. This is a topic worthy of a future discussion.”

So let’s discuss.

First of all, indeed, perseverance is the key to success in any field—from business to art to sports. Heck, to life. A famous quote from Calvin Coolidge sums it up:

Nothing in this world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not; the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.

Now that we’ve established perseverance as the baseline, let’s discuss getting discovered when, frankly, nobody knows who the heck you are. I realize RLM is working with a small publisher. So take the following as discussion points to take up with your publisher as partner in getting your book seen. For those about to go indie, attend:

- The three rules of discoverability

The three rules of real estate, as we all know, are location, location, location. The three rules of discoverability are eyeballs, eyeballs, eyeballs. You want as many new eyes on your pages as possible.

That’s why you should never consider your first book as a money maker but as a loss leader. This is a common strategy in a new business. It means selling a product or service at a price that is not profitable but designed to attract new customers in order to sell them more products down the line. Indeed, this is exactly what Amazon did in its early years (when the know-it-alls were calling it Amazon dot bomb!)

In the same way, you want your first book in the hands of as many readers as possible, even if it means little or no income. And the best way to do that is via:

- Kindle Select

For book distribution there is nothing more powerful than the Amazon algorithms. Which means putting your book into Kindle Select. We’ve had many a discussion about going wide and going exclusive. But since we’re talking about a first book and no name recognition, Select gives you the best shot and attracting readers in the world’s largest bookstore. See my going exclusive post, especially the part about working in tandem with a deal-alert newsletter like BookGorilla, ENT, and The Fussy Librarian (a list of other deal-alert sites can be found here).

- Start growing your email list

In the back matter of your book (and on your website) have a way for readers to sign up for your “occasional emails” with deals and updates. I don’t offer a “newsletter” because I believe newsletter fatigue is a thing. What you want are emails that look like messages to friends, not sales brochures to customers. And offer something free in return for signing up. I do it this way.

- Produce books as fast as you comfortably can

Your career, recognition, and income are tied to your ongoing productivity. Of course, your books have to be quality, a hazy concept that basically means the kind of book a wide swath of readers will enjoy reading. This is a matter of craft, which is why TKZ is around. Your continuing education in the craft should run on a parallel track with your output. Never stop learning.

Always have a new book you’re working on and one or more in development. Be like a movie studio.

- Killer covers

We all know the importance of covers. This is no place to skimp. Spend the money to commission a cover that looks every bit as good as anything put out by a Big 5 publisher. Your teenage son or a Fiverr guy is not the way to go.

Go to Amazon and start looking at covers by bestselling authors in your genre. Find designs that jump off the screen. Save them as examples.

Then find a designer. One I have used with happy results is Damonza. Expensive yes, but you get what you pay for. (A list of cover designers can be found here.)

Your designer should look at the examples you’ve saved from Amazon and put that together with your ideas for the book.

If you’re working with a small publisher ask for cover input. You might consider paying for your own designer and asking the publisher to split the cost.

- Book description

You need to become a master copywriter for your own books. See the great post by Sue and the comments thereto. Write three or four descriptions, trying different angles. Show these to some people and get feedback—which one creates the greatest desire to read the book?

- A+ Content

As Terry pointed out recently, Amazon now offers all authors and publishers the addition of A+ Content. It’s another level of sell that costs nothing. If you’re conversant with Canva, design is pretty simple.

- Your author profiles

Set up your Amazon author page and BookBub profile. No cost for creation and easy to nurture.

- Price

A lot of digital ink has been poured out on pricing strategy. The current wisdom is that an ebook price of $2.99, $3.99 or $4.99 is the sweet spot. For a new author, $2.99 might be the place to start. Anything from $5.99 on up starts to trigger customer resistance. There’s no reason for that. Remember, loss leader and eyeballs.

- Social media

So much has been written about this topic (see the recent Ben Lucas TKZ post). I’ll just summarize my own feeling: social media is not a good place to sell books. I may, however, be behind the times. I probably should be doing dance videos on TikTok. (Or maybe not. There are some things you can’t unsee.)

My standard advice has been to find one or two platforms you enjoy and use the 90/10 rule: 90% of the time provide helpful or entertaining content, and 10% on promoting a book or a deal. Just don’t overuse social media to the detriment of your main task: producing books.

- Advertising?

Advertising on Amazon, BookBub or Facebook is a bit complicated. You can spend a lot of time and money trying to figure out what works best for you. I therefore cannot recommend it for new authors because the EROI—Eyeball Return on Investment—is too low. If anyone has managed to crack the code on this kind of advertising, please tell us about it in the comments.

Conclusion

Getting noticed in the roiling sea of content can seem a daunting task. You know why? Because it is. There are over 3,000 new books that come to market every day. It’s therefore crucial that you manage your expectations and keep moving forward. There is an inner power in being action-oriented. (That’s why I like page-count quotas. I can feel accomplished every day.)

Andre Dubus once said, “Don’t quit. It’s very easy to quit during the first ten years.”

Ten years from now you can revisit your decision to become a writer. Until then:

A controversy over an award-winning female thriller author has broken out in Europe. That’s because the female thriller author doesn’t exist. “She” is really three men who have been writing under the pseudonym Carmen Mola. When one of their novels won a million-euro prize, the trio

A controversy over an award-winning female thriller author has broken out in Europe. That’s because the female thriller author doesn’t exist. “She” is really three men who have been writing under the pseudonym Carmen Mola. When one of their novels won a million-euro prize, the trio

You are offered $10,000 to spend a night alone in a haunted house. Many people swear it’s truly haunted—including a wild-eyed coot whose hair turned white after his one-night stay.

You are offered $10,000 to spend a night alone in a haunted house. Many people swear it’s truly haunted—including a wild-eyed coot whose hair turned white after his one-night stay.