By Larry Brooks

What seems to some to be so simple turns out to be anything but. Because we read excellent stories all the time, and they really do seem, well, if not simple, then at least clear and clean and accessible, and therefore not beyond our means.

The blank page both calls to us and mocks us. And so we fill it up with what we have to offer, arising from the pool of what we know, fueled by dreams we dare not utter aloud… sometimes soured by what, either in ignorance or arrogance or simple haste, we’ve chosen to ignore.

But too often it is what we don’t know — especially when we don’t actually know what we don’t know — that is our undoing.

Because, in spite of all the books and workshops and websites and analogy-slinging writing gurus out there, we cling to the limiting belief that there are no “rules.” The mere mention of that word causes you to rebel with artistic indignation, even conclude that principles and standards are mere “rules” with polite sensibilities — this one, too, being our undoing — and from there we decide that we can write our stories any way we please.

Because this is art, damn it.

Often we don’t find out that what we have to offer isn’t good enough until the rejection letter arrives. Or the critique group pounces like Simon Cowell on a bad day. Or when a story coach doesn’t tell you what you want to hear.

As one of the latter, at least until lately, my job involves telling writers — frequently — that their story is coming up short, followed by my best shot at explaining why. To explain that the wheels fell off, very often at the starting gate. It’s the why part that allows me to sleep at night, because I’ve been on my share of the receiving end of the sharp pokes this business delivers. But like a doctor giving a screaming kid a vaccination shot, I take solace in the hope that once the sting subsides the writer will see the pit into which they are about to tumble.

And that they may finally begin to know what they don’t yet fully know.

The Trouble with Craft

Craft — the mechanics and architecture and sweat of putting a story together — is complex, if nothing else than for its sheer immensity. It’s anything but simple, complicated by a writing conversation out there that seeks to over-simplify it. Even in those stories that inspire us, bestsellers and favorite authors and even the classics, we’re witnessing the symmetry and fluid power of simplicity on the other side — beyond — complexity.

I’ve sought to put fences around it all, create labels and levels and subsets of supersets and connect those dots in ways that facilitate navigation along that path. Six core competencies, six realms of story physics, and about five dozen subordinated corners of the craft aligned under those twelve flags.

Trouble is — just like in love and careers and gambling — you can get them all technically right… and your story can still fall short. And that’s the thing — the holy grail of “things” we need to understand — that separates craft from art. Unpublished from published. Frustrating from rewarding.

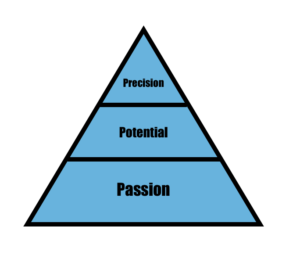

So without minimizing any of the myriad corners and nuances of craft — indeed, they remain eternal, consistent and the non-negotiable ante-in — allow me to once again attempt to simplify. To break it down into three buckets, three qualities, three goals, that any successful story will embody to some extent.

Three essences to shoot for (apologies to the more than one writer who can’t quite wrap their head around the notion of essence… in the business of words, it is good to know what they mean). Three qualities to evaluate about your story intention, and then your execution.

Three things to grade yourself on.

Three things about your story… things that readers will, upon finishing your story, notice.

If at least one of those grades isn’t an “A,” then you’ve got more work to do. It’s a mission impossible moment: your job, should you choose to accept it… is to write a story that competes for readership.

This will help.

The Fiction Trifecta

No surprises here. But be honest, have you really evaluated your story on these things, regarded as criteria? Have you asked yourself what your strategy will be to optimize one or more of these things within your narrative?

In no particular order, because each stands alone as a potential windfall:

Intrigue – A story is often a proposition, a puzzle, a problem and a paradox. When you (the reader) find yourself hooked because you have to know what happens… or whodunnit… or what the underlying answers are… then you’ve intrigued your reader. It may or may not have an emotional component to it — mysteries, for example, are usually more intellectual than emotional, they’re intriguing because the clues lead somewhere, and we want to know where, even see if we can get there first.

Mysteries, as a genre, are almost entirely dependent upon reader intrigue. Not necessary “dramatic intrigue” within the story itself, but rather, the degree to which a reader is “intrigued” with the questions the story is asking, as well as the characters that pose the questions.

But this kind of intrigue isn’t limited to mysteries. Sometimes intrigue is delivered by the writing itself. A story without all that much depth or challenge can be a lot of fun, simply because the writer is funny. Or scary. Or poetic. Or brilliant on some level that lends the otherwise mundane a certain relevance and resonance. Make no mistake, these attributes are, at their core, a form of intrigue.

Emotional Resonance – When a story moves you, which so many great stories do, it’s because we feel it. It makes us cry. Laugh. It makes us angry. It frightens, it seduces, it confounds and compels.

Les Miserables isn’t the classic it is — book, stage and screen — because we must find out what happens or whodunit. No, it works because it makes us weep. John Irving’s Cider House Rules is a modern classic because it pushes buttons, forces us to confront alternatives, compelling us to behold the consequences of our choices reduced to the realm of feeling.

Same with The Davinci Code, another modest success.

Every love story, every story about injustice and pain and children and reuniting with families and forgiveness — name your theme — is dipping into the well of emotional resonance for its power.

Vicarious Experience – reader, meet Harry Potter. Go with him on an adventure to a place you’ll never experience otherwise. Or Hans Solo. Or James Bond. Or Sherlock Holmes or Merlin or Stephanie Plum or some alien with an agenda. The juice of these stories isn’t so much the dramatic question or the plucking of your heart strings as much as the ride itself. The places you’ll go, the things you’ll see, the characters you’ll encounter, the things you’ll experience and encounter.

Of course, emotionally-vicarious experience (versus setting-driven) can be a ride, as well — a story about falling in love, or getting fired, or winning the lottery — and when that happens you’ve been given an E-ticket on the Slice of Life attraction. These stories strike two of these Trifecta chords by making us feel the experience of falling in love, or feeling loss or simply walking a mile in shoes that seem compellingly familiar.

None of this is new. But few writers shoot for these as targets as their story emerges, taking for granted that they will be in evidence. But when used as criteria and quantitative raw grist, you are better equipped to understand how well your story will work… or not… as the narrative comes together, rather than because of the sum of its parts.

The common factor here is this: something compelling about the story.

Either intellectually, emotionally, or on some other level (usually the result of a combination of these three gold standards). An allure that resides beyond the tricky or original or otherwise “interesting” nature of its concept.

Your concept, however tricky or original or interesting, isn’t completely compelling until it lands on one or more of those three powerful forces: intrigue… emotional resonance… vicarious experience. A story about aging backwards, for example, or about going to another planet, or finding a secret code… a story driven by something conceptual… may not be enough.

It’s the difference between a beautiful store window mannequin and a beautiful model strutting the runway. One percolates intrigue, the other… just lies there, cold and still.

The goal is to juice your concept with some combination of the Trifecta elements.

Until that happens, that’s all you have: an idea. In this business, concepts are commodities. But intrigue, emotional resonance, and vicarious experience… those are pure gold.

*****

If you’re in a mood for a deeper dive into craft, I invite you to consider my training videos, available now on Vimeo. Even better, through February they are all HALF OFF… just use this code — Feb50off — in the checkout sequence for each video you want to download.