If you could be best friends with an author (alive or dead), who would you choose and why?

Monthly Archives: September 2016

Yes, He Really Said That

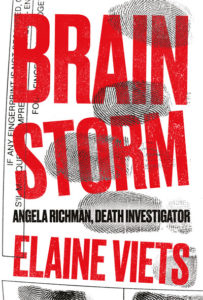

By Elaine Viets

Dr. Gregory House is a creature of fiction. Real doctors aren’t that insensitive, are they?

Oh, yes they are. I had a brain surgeon who made Greg House look like Marcus Welby.

Dr. Jeb Travis Tritt is the brain surgeon who saved my life after I had six strokes, including a hemorrhagic stroke, in April 2007. That’s not his real name, and he doesn’t look or act like the brain surgeon in my new mystery Brain Storm. But Dr. Tritt, as I baptized him, was a real character. I couldn’t make up what he said – I’m not that creative.

In fiction and reality, Dr. Tritt is a brilliant surgeon with a lousy bedside manner. He saws open skulls for a living, so I expected him to be a little strange. But hey, so am I.

In fiction and reality, Dr. Tritt is a brilliant surgeon with a lousy bedside manner. He saws open skulls for a living, so I expected him to be a little strange. But hey, so am I.

Brain Storm, the first Angela Richman, Death Investigator novel, is set in mythical, ultrawealthy Chouteau Forest, Missouri. Angela and I had blinding headaches and other classic stroke symptoms that sent us to the ER. There we were misdiagnosed by the neurologist on call, who said we were “too young and fit to have a stroke.” This comment is staggeringly stupid, though I didn’t know it at the time. Babies can have strokes. Dr. I. M. Incompetent told Angela and me to come back in four days for a PET scan.

Brain Storm, the first Angela Richman, Death Investigator novel, is set in mythical, ultrawealthy Chouteau Forest, Missouri. Angela and I had blinding headaches and other classic stroke symptoms that sent us to the ER. There we were misdiagnosed by the neurologist on call, who said we were “too young and fit to have a stroke.” This comment is staggeringly stupid, though I didn’t know it at the time. Babies can have strokes. Dr. I. M. Incompetent told Angela and me to come back in four days for a PET scan.

We never got that scan. Instead, we had a series of strokes, brain surgery, and a coma, and encountered Dr. Jeb Travis Tritt. After brain surgery, Angela and I were in a coma for a week and spent three months in the hospital.

We never got that scan. Instead, we had a series of strokes, brain surgery, and a coma, and encountered Dr. Jeb Travis Tritt. After brain surgery, Angela and I were in a coma for a week and spent three months in the hospital.

That’s where Angela and I parted company. When she came out of the coma, she learned that the doctor who nearly killed her had been murdered. The chief suspect was Dr. Tritt. Angela, still drugged and hallucinating, was determined to save the doctor who saved her. I can’t kill the doctor who misdiagnosed me. Except in fiction.

But I did experience Dr. Tritt’s midnight monologues, and put them in Brain Storm.

But I did experience Dr. Tritt’s midnight monologues, and put them in Brain Storm.

When Dr. Tritt got off work at midnight, he’d stop by my room. First he’d check my healing wound – a hideous cobblestone of a bump. Then he’d settle in for a monologue, talking nonstop for two or three hours. I was a captive audience – I couldn’t walk yet. He’d make jaw-dropping comments. I was heavily drugged and still talking to imaginary friends. But I knew I had a real find. Dr. Tritt’s visits were a gift. It took me nine years to use it.

One night Dr. Tritt said, “Do you remember anyone talking to you while you were in a coma?”

“No,” I said. “No tunnel of light, no relatives waiting on the other side. I didn’t see or hear anything.”

“Thank God,” he said. “I used to stop by every night and say, ‘Elaine! This is God! Wake up!’ But the nurses made me quit.”

Why did a surgeon spend hours talking to me instead of going home? He answered that question in another monologue.

Why did a surgeon spend hours talking to me instead of going home? He answered that question in another monologue.

“My wife is divorcing me,” he said. “She likes to shop and I don’t make enough money. She thought brain surgeons would be rich, but I don’t get that much. I only got three thousand dollars for your surgery. She wasn’t that good in bed, anyway. She just laid there, like you did, except you were in a coma.”

Huh? It didn’t occur to the doctor that perhaps his performance might have something to do with his wife’s lack of enthusiasm. The doc wasn’t coming onto me. My face was swollen, my skin was bright red thanks to an allergy to some medication, and half my hair was shaved off.

I’d always been proud of my long hair. I was shocked when I saw it had been partly shaved off for the surgery. Late one night, Dr. Tritt said, “I’m sorry about your hair.”

“In the grand scheme of things, it’s not the end of the world,” I said.

“I burned your hair because I knew you were going to make it,” he said. “If my patients are going to die, I save their hair because they like to look good in their coffins.”

I was speechless. But then I thought: What would he say if I was going to die? Would he come by one midnight, hand me my hair and said, “Elaine, you’re screwed. But here’s your hair. You’ll look great in your coffin.”

I was speechless. But then I thought: What would he say if I was going to die? Would he come by one midnight, hand me my hair and said, “Elaine, you’re screwed. But here’s your hair. You’ll look great in your coffin.”

Good old Jeb Travis Tritt. This real life character saved my life. Now I hope he can help me pay off those hospital bills.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Brain Storm is on sale as a trade paperback, audio and e-book amzn.to/2awPsIe

Brain Storm is on sale as a trade paperback, audio and e-book amzn.to/2awPsIe

Win an autographed hardcover of Elaine’s seventh Dead-End Job mystery, Clubbed to Death. http://elaineviets.com/index.php?id=contests

How to Write 10,000 Words in a Day, and Why You Should Give It a Shot (at least once)

The most words I’ve ever written on a fiction manuscript in a fourteen hour period is 11,214. I was on a solo writing retreat in a secret location (okay, it was at an AirBnB apartment in St. Louis), laboring over the final push for The Abandoned Heart. My deadline loomed, and I was finding myself way too distracted at home to get the book drafted in time. All told, over the three and a half days of my retreat, I wrote over 26,000 words—certainly more words than I’d ever written before on a first draft in any similar time period.

Part of why I was successful was that I knew I was paying for the time away from home, and I didn’t want to disappoint myself or anyone else. It cost me about $400 for the apartment rental, plus another $125 for gas (St. Louis is two hours away), groceries, and a couple of restaurant meals. My family paid, too, in that they had to pick up the slack at home. The circumstances were definitely extraordinary. But it wasn’t my first time at the Big Daily Word Count Rodeo.

I was lured into my first 10K day a few years back by my thriller writer friend, J.T. Ellison. She was looking for a partner in crime—someone to check in with, someone to be accountable to—and she knows I’m game for all sorts of shenanigans. We’ve climbed the 10K summit many times now, and we even have tee shirts to celebrate our achievement.

If you peruse the Internet, you will find several examples of people talking about tackling the big 10K. But the methods all boil down to a few key elements.

Let’s talk about the whys first.

1. Resistance. If you only have a dozen hours in a day to write 10,000 words, you’re going to have to write fast. Really fast. You won’t have time to worry about what your parent/child/rabbi/auntfanny/spouse/eleventhgradeteacher/coworker will think about your work. You won’t have time to be afraid. You won’t have time to fiddle with word choice and as-you-write edits. The beauty of this goal is that you must put your internal editor on notice: She has to work fast, or get the hell out of the way. Resistance has no claws or hooks in this scenario.

2. Get those words out of your head and down on paper. Your story isn’t doing anything for anyone by sitting there, overcooking in your brain. I’ve never tried to do this below the 30K mark in a story, but there’s no reason why you can’t. It’s a story exploder, in a good way. Even if you’re not quite sure where a story is headed, the story knows. That fabulous subplot that woke you briefly at two in the morning, and you forgot on waking? It’s still in there, and your agile, in-overdrive mind will pop it out just when you need it.

3. Get a big jump in your word count. If you’re going for a 100K manuscript, 10K is ten percent of your total. That’s huge for one day, and the satisfaction you’ll enjoy from that accomplishment will stick with you for the duration.

4. First drafts aren’t final drafts. Perfection is not (ever) required. This is the place to let your storytelling mind play. Write now (and it will sometimes feel like you’re just typing and that’s totally okay), edit later. Don’t imagine that this will be finished work, but do be prepared to be pleasantly surprised at how readable it is.

5. You write just as well quickly as you do when you write more slowly. I’m not kidding when I say you’ll be surprised at the quality of the writing you produce. With breaks, you’ll be writing between 1000 and 1200 words an hour (my fastest is about 1400), which isn’t unusual. The unusual part is doing it hour after hour.

6. Why not? Test yourself. Push yourself. Life is too short to dawdle. This isn’t something you have to do once a week, once a month, or even once a year. There are lots of things we devote entire days to that we despise. Why not set aside a day to do something that you love?

Resistance will come up with a lot of excuses for why you can’t do this: It’s a gimmick; You don’t have time; Nobody can write decently at that pace; Your family won’t give you time/space to do it; The world can’t possibly do without you for a dozen hours; It’s dumb and unprofessional; You will fail.

There have been a few times when I’ve completed all the arrangements for a 10K day (always at home), and someone forgot their homework, lunch, or got sick. Or the furnace broke or the phone rang ten times and it was my mother. I only got in 8K or 6K or 5K on those days. But I had at least 5K more than I did the day before. The important thing was that I committed to the time, to the work, and that I got a good chunk of words written.

Let’s talk about the hows of a 10K day:

- Commit. Decide you’re going to do it, and take it seriously. Sure, things will crop up and demand your attention, but if you’re committed, you won’t be derailed. Stay off of social media for the day.

- Enlist. Enlist your family in the project. Announce your intention to disappear into your writing for the day, and make (enjoyable) plans for them or yourself to be away. If they’re already used to your professional attitude toward your own writing, this won’t be unusual for them. If this is new for you (and them), you might want to take yourself off to a hotel, a friend’s house, or a comfortable library with food facilities nearby. Show them what 10K words look like. They will be impressed that you want to produce so much material. (And if they’re not, too bad for them because they should be.)

- Choose your ground. Find somewhere comfortable to work where you won’t be tempted to nap frequently, or get on the Internet. For the random 10K day, I prefer to work at home because I can be as relaxed as I like. Declutter your workspace so you can concentrate on the work and not be distracted by bills, school or work communications, etc. Dress comfortably and make sure your chair is comfortable, too.

- Plan your breaks, plan your food. The Pomodoro timer method works well. You can get up and stretch your legs for five minutes after each twenty-five minute work block, and take a longer break every couple of hours. Or you can set up any system that you know works for you. The idea is to be consistent. Don’t work through your breaks. It may sound silly to plan your food, but it’s a critical detail. If you only have a fifteen minute or five minute break, every minute counts. When you emerge from your writing cocoon to find a sandwich in the fridge, or an ounce of nuts, or some fruit and chocolate waiting on the kitchen counter, it will seem magical.

- Plan your writing. Make sure you’re very familiar with the manuscript, have a solid idea about what you want to write, and where the story is going. Your list should be completed the day or night before your 10K day. My chapters are about 2K words long, so that’s a goal of five chapters for an all-day session. Remember to write in scenes, and to keep the story moving forward.

- Keep track. Make a note of your growing word count. Every time you stop for a break, write down how many words you’ve written. They will add up quickly! Be sure to time your breaks, just like you do your writing sessions. Save your work frequently.

- Bring a friend. Bring along a friend (not necessarily in person) to participate so you can encourage one another. Plus, you get to celebrate together at the end.

I know it’s a lot to digest all at once, but I promise that the rewards are huge. I strongly encourage you to give it a shot.

How many words did you write on your very best word count day? Do you have any stories you want to share?

Goodreads is giving away copies of all three novels in my Bliss House dark suspense trilogy, including The Abandoned Heart, which will be released on October 11th. Enter here for a chance to win.

The 3 (Or 7, or 36) Basic Plot Lines In Fiction

By Kathryn LIlley

According to some writing gurus, there are somewhere between seven to 36 basic plot lines in fiction (depending on which expert you believe) that structure most works of fiction. Here is a list of some of the plot lines that are often described as basic elements comprising all works of fiction:

Happy Ending/Comedy

Tragic Ending

“Literary” Ending (Plot revolves around a question or sense of fate, rather than actions or decision)

Other sources break down the Big Three plot lines into more specific categories:

Overcoming the Monster

Quest

Rags to Riches (Or Riches To Rags And Back To Riches)

Voyage And Return

Mystery

Crime Pursued By Vengeance/Prevention of Bigger Crime (a plot line that would define most thrillers)

I have to admit, I started looking into the notion of basic plots because I once took a Hollywood screenwriting seminar delivered by one of the better known screenwriting teachers in LA. He first introduced me to the idea that there were only a limited set of original plot lines in fiction, most of which harked back to classic Greek drama.

Check out this link to a summary of some of the prevailing notions of a limited set of fundamental, archetypal plot lines in fiction, and let me know–are people getting carried away with the idea? I think a story’s plot itself is less Important than the way that story is told–the plot, however basic and fundamental, must be told in a way that is fresh, original, and compelling. And making a stale plot seem fresh and new (aka rags to riches==>Cinderella==>Pretty woman): that is the hardest part of writing.

But I suspect I my story structure and story coach colleagues (and everyone else) might have some thoughts about this topic. Please share yours?

From The List of Elite Writing Tips

by Larry Brooks

It’s amazing that nobody has compiled such a list, at least that I know of. Sometimes a little morsel of writing wisdom is so rich, so illuminating and powerful, it doesn’t require a lecture or a blog post or a book.

I’ll try to hold to that here, after I lay one on you.

I bet you, too, can think of a handful of powerful writing tips just from this prompting.

Often I kick off my writing workshops by asking folks to jot down their all-time favorite writing tip, and then open things up for a lively discussion.

Almost all of the tips offered are powerful–except the one that says there are no rules or principles, just make up your story as you go along… that one can be downright lethal–so the discussion focuses on the context of why these tips work, and what brought the writer to that particular career-changing realization.

Not all writing tips are golden, though,

Some require a deeper discussion to be fully understood. Not because they are overwhelmingly complex, but because at a glance they can be misleading. (Too many writers operate from that at a glance context.) I can think of at least one popular writing book with a title like that, suggesting “truth” that is, in fact, context-dependant and nothing other than a risky opinion (“hey kids, do it like I do it!”). The book itself is actually fine (in fact, it contradicts the title; it ends up being more about process than what makes a story work), adding to the confusion even with the best of intentions.

There is another tip, though, that transcends opinion to become holy writ. I’ve seen it work wonders for writers who have struggled to move forward without ever really wrapping their head around it. With a more open mind, though (and yes, it’s a shame that we sometimes need an open mind to see that which is simply, obviously and always true, in writing and in life), it can change your writing journey the moment you see it, provided it parts the curtain of your understanding.

This one is especially true for genre fiction, so us Zoners should paste it onto our monitors, because it will never fail us. It is this:

It isn’t a story until something goes wrong.

This connects to so many principles of storytelling.

And yet, newer writers in particular get stuck writing about something–a character, a place, a time, an issue, all without plot-driven conflict or antagonism other than the hero’s inner issues–rather than writing about something happening in the context of something gone wrong for your protagonist, launching the hero on a dramatic quest that unfolds under escalating pressure from antagonistic opposition, threat, urgency and emotionally-resonant stakes.

You can start with something going wrong, and add character, setting, theme and structure from there. Of you can start with character and/or there and look to add conflict–something has gone wrong–to it.

But no matter how you start, you can’t finish until something really does go wrong.

What is your favorite writing tip? id you hear it because you needed to (one of those when the student is ready the teacher shall appear moments), or is it a baseline truth from which you have always written?

Did you hear it because you needed to (one of those when the student is ready the teacher shall appear moments)? Or is it a baseline truth from which you have always written?

******

On another note… I’ve launched a new website in support of my new relationship-salvage book, Chasing Bliss. You can check it out HERE (including an in-depth author interview).

Why Plot is Essential to Character

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

If you ever find yourself among a group of writers, writing teachers, agents or editors; and said group is waxing verbose on the craft of fiction; and the subject of what fiction is or should be rumbles into the discussion, you are likely to hear things like:

If you ever find yourself among a group of writers, writing teachers, agents or editors; and said group is waxing verbose on the craft of fiction; and the subject of what fiction is or should be rumbles into the discussion, you are likely to hear things like:

All fiction is character-driven.

It’s characters that make the book.

Readers care about characters, not plot.

Don’t talk to me about plot. I want to hear about the characters!

Such comments are usually followed by nods, murmured That’s rights or I so agrees, but almost never a healthy and hearty harrumph.

So, here is my contribution to the discussion: Harrumph!

Now that I have your attention, let me be clear about a couple of items before I continue.

First, we all agree that the best books, the most memorable novels, are a combination of terrific characters and intriguing plot developments.

Second, we all know there are different approaches to writing the novel. There are those who begin with a character and just start writing. Ray Bradbury was perhaps the most famous proponent of this method. He said he liked to let a character go running off as he followed the “footprints in the snow.” He would eventually look back and try to find the pattern in the prints.

Other writers like to begin with a strong What if, a plot idea, then people it with memorable characters. I would put Stephen King in this category. His character work is tremendous. Perhaps that is his greatest strength. But no one would say King ignores plot. He does avoid outlining the plot. But that’s more about method.

I’m not talking about method.

What I am proposing is that no successful novel is ever “just” about characters. In fact, no dynamic character can even exist without plot.

Why not? Because true character is only revealed in crisis.

Without crisis, a character can wear a mask. Plot rips off the mask and forces the character to transform––or resist transforming.

Now, what is meant by a so-called character-driven novel is that it’s more concerned with the inner life and emotions and growth of a character. Whereas a plot-driven novel is more about action and twists and turns (though the best of these weave in great character work, too). There is some sort of indefinable demarcation point where one can start to talk about a novel being one or the other. Somewhere between Annie Proulx and James Patterson is that line. Look for it if you dare.

We can also talk about the challenge to a character being rather “quiet.” Take a Jan Karon book. Father Tim is not running from armed assassins. But he does face the task of restoring a nativity scene in time for Christmas. If he didn’t have that challenge (with the pressure of time, pastoral duties, and lack of artistic skills) we would have a picture of a nice Episcopal priest who would overstay his welcome after thirty or forty pages. Instead, we have Shepherds Abiding.

If you still feel that voice within you protesting that it’s “all about character,” let me offer you this thought experiment. Let’s imagine we are reading a novel about an antebellum girl who has mesmerizing green eyes and likes to flirt with the local boys.

Let’s call her, oh, Scarlett.

We meet her on the front porch of her large Southern home chatting with the Tarleton twins. “I just can’t decide which of you is the more handsome,” she says. “And remember, I want to eat barbecue with you!”

Ten pages later we are at an estate called Twelve Oaks. Big barbecue going on. Scarlett goes around flirting with the men. She also asks one of her friends who that man is who is giving her the eye.

“Which one?” her friend says.

“That one,” says Scarlett. “The one who looks like Clark Gable.”

“Oh, that’s Rhett Butler from Charleston. Stay away from him.”

“I certainly will,” says Scarlett. (The character of Rhett Butler never appears again.)

Scarlett then finds Ashley Wilkes and coaxes him into the library.

“I love you,” she says.

“I love you too,” Ashley says. “Let’s get married.”

So they do.

One hundred pages later, Scarlett says, “I really do love you, Ashley.”

Ashley says, “I love you, Scarlett. Isn’t it grand how wonderful our life is?”

At which point a reader who has been very patient tosses the book across the room and says, “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

What’s missing? Challenge. Threat. Plot! In the first few pages Scarlett should find out Ashley is engaged to another woman! And then she should confront him, and slap him, and then break a vase over the head of that scalawag who looks like Clark Gable! Oh yes, and then a little something called the Civil War needs to break out.

These developments rip off Scarlett’s genteel mask and begin to show us what she’s really made of.

That is what makes a novel.

Yes, yes, you must create a character the readers bond with and care about. But guess what’s the best way to do that? No, it’s not backstory. Or a quirky way of talking. It’s by disturbing their ordinary world.

Which is a function of plot.

So don’t tell me that character is more important than plot. It’s actually the other way around. Thus:

- If you like to conceive of a character first, don’t do it in a vacuum. Imagine that character reacting to crisis. Play within the movie theater of your mind, creating various scenes of great tension, even if you never use them in the novel. Why? Because this exercise will begin to reveal who your character really is.

- Disturb your character on the opening page. It can be anything that is out of the ordinary, doesn’t quite fit, portends trouble. Even in literary fiction. A woman wakes up and her husband isn’t in their bed (Blue Shoe by Ann Lamott). Readers bond with characters experiencing immediate disquiet, confusion, confrontation, trouble.

- Act first, explain later. The temptation for the character-leaning writer is to spend too many early pages giving us backstory and exposition. Pare that down so the story can get moving. I like to advise three sentences of backstory in the first ten pages, used all at once or spread around. Then three paragraphs of backstory in the next ten pages. Try this as an experiment and see how your openings flow.

- If you’re writing along and start to get lost, and wonder what the heck your plot actually is, brainstorm what may be the most important plot beat of all, the mirror moment. Once you know that, you can ratchet up everything else in the novel to reflect it.

Do these things and guess what? You’ll be a plotter! Don’t hide your face in shame! Wear that badge proudly!

Reader Friday – If you could travel to one place you’ve read about…

First Page Critique – The Truth About Morality

For your reading enjoyment we have “The Truth About Morality” submitted anonymously for critique of the first 400 words or so. My feedback to follow. Join me with your constructive criticism in comments.

My face, well rested and laminated in a childlike innocence, looked the same as before. When I opened my lips to a smile, smooth skin stretched itself around white teeth, eyes bright and honest.

Nothing there, I told myself.

And still, my face from this day on would hide a murder.

A righteous murder some might argue, others would disagree. Alvin would say that the act had been neither right nor wrong. Morality nothing more than a construction we implement on ourselves.

The innocence of the spontaneous wasn’ a possible justification. Neither had I been forced. On the contrary, there had been many instances when I could have told them I didn’ want us to follow through with the plan.

I knew I had acted voluntarily. Despite this the feeling that advanced on me was one of dread.

I went to Livia and Alvin’ part of the apartment. Even though there were plenty of rooms to choose from they had their bedrooms next to each other. I started with Livia’ room. I wanted to understand them. Because it suddenly seemed that I, even with my feverish studies of the two of them, had overlooked one aspect. I just didn’ know what it was that I had missed.

The room had Livia’ scent of expensive perfume and nonchalance. I started lifting things and when that wasn’ enough I opened a drawer and then another one. I was careful. Livia’ room wasn’ neat but there were aspects of it that looked orderly, magazines sorted by month, philosophy books opened on a special page. I pushed aside the doors of the cabinet and found Livia’ clothes. Jeans were separated from pants, she had a section for t-shirts and one for the oversized cashmeres sweaters she favoured. The shades shifted from white to black, with plenty of blue and grey nuances in between, the colours of a sky minutes before the storm.

The search that had started out almost by accident turned meticulous. I crawled under the iron framed bed, swept my fingers alongside the outdated bottom of steel springs, trailed the blackened legs.

I rose, elongated shadows sliced the room. Everything was still, the world locked in a devotional silence. But inside me an alarm kept ringing, high pitched and toneless. I knocked on the walls, trying to pick up a hollow sounding note. When I didn’ find anything I moved over to Alvin’ room.

FEEDBACK

Although I liked some of the turns of phrases in this piece and found the character’s internal thoughts were interesting, I wanted more. The author left me wondering what this person (not sure of gender) is searching for after they presumably killed someone. From this intro, we do not know where this murder took place or when. I expected the body to be there, but that was never expressed. I had to read this a few times to search for something I had missed. It would appear the murder was committed by an “us” as well. Although the mystery left me curious to learn more, the writing needs work to anchor the character more realistically and keep the reader turning the pages. Here are some suggestions:

WHERE TO START – The entire intro takes place in the character’s head with only minimal action of him or her searching a room. I wanted there to be more. I had more curiosity about the killing, rather than a search of a room for a person I don’t care much about. The writing doesn’t make me empathetic for this person, even if the murder had been “righteous.” This reads as if it’s from a later scene, as if I’m starting after something important happened that’s not part of the story.

I’m assuming the character is looking in a mirror or reflective glass to see their face as the story opens. I’m not a fan of the ploy of describing the character’s appearance as they look in a mirror–because it’s so cliche–but if the author wants to keep that part, they should establish there is a mirror, otherwise the point of view is off since a character can’t see himself otherwise.

GIVE THEM SOMETHING TO DO – As a suggestion for this intro, I would recommend you give the character something more to do and focus on. Add tension. They could watch a spiraling stream of crimson against a white porcelain sink as blood drains off their shaking hands as they desperately wash the skin until it is raw. When they look into the mirror, what do they see? The notion of a murder could be only a tease that is not explained until later.

SENSE OF URGENCY – For someone who has killed another human being (presuming the death occurred recently), there does not appear to be any urgency to the character’s actions. Their search of Livia’s room is methodical and not rushed. I’d like to see more emotion in this intro, given that a death has occurred. When the character knocks on the walls for a hollow sound, are they concerned they’ll be heard?

ADD DEPTH TO THE CHARACTER’S POV – Have the character react to the neatly stacked magazines or the perfume. What do they think? Do they resent the lingering essence of Livia? I wouldn’t waste a scene by merely describing the character’s calm search. Add emotion by stressing out the character. Is Livia a victim or a fellow killer? Are there precious seconds before this person is discovered searching the room?

FIRST PERSON – It’s been my experience that a writer should infuse gender as quickly as possible, before the reader gets too far along and forms a hard to overcome attachment to one sex or the other. Keep in mind that the character can only see through their own eyes and not upon themselves, so use things like – fingernails, articles of clothing, types of shoes, hair length, or perfume/cologne to hint at the gender as soon as possible.

TYPOS – I’m not sure why there are so many of the same type of typos (bolded in red) where a single letter in a contraction is omitted – ie. wasn’ & didn’ and possessives with ‘s. “Oversized” should probably be hyphenated. There is also this – “cashmeres sweaters,” which should be “cashmere sweaters.” This could be attributable to software issues, but an editor or agent would not want to see this, even if it is explainable.

FOR DISCUSSION

Please share your thoughts on this introduction to help this courageous author develop this story. What do you like about the intro? What would you change?

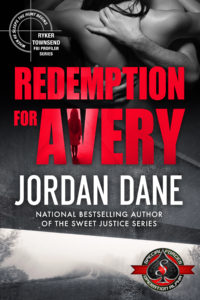

Redemption for Avery – $1.99 ebook

When he sleeps, the hunt begins.

FBI Profiler Ryker Townsend is a rising star in Quantico’s Behavioral Analysis Unit, but his dark secret could cost him his career. When he sleeps, he has visions of his next case. He sees through the eyes of the dead, the last images imprinted on their retinas. His nightmares are riddled with clues he must decipher to hunt humanity’s Great White Shark—the serial killer.