by Michelle Gagnon

Recently there was a query letter discussion on one of the lists that I frequent. Everyone chimed in with differing opinions about what works, and what almost guarantees one of those soul-crushing form letter rejections. It made me reflect back on my own letters (and yes, you read that correctly: letters, plural).

Out of curiosity, I asked the multi-talented Luc Hunt from my agency (the Philip G. Spitzer Literary Agency) to dissect two of my query letters. The first was for a book that was roundly rejected (rightfully so, I must say) by every agent I queried.

The second was the letter that got me a nibble for a full manuscript, which eventually led to representation.

So here’s the good, the bad, and the cringe-worthy. Luc’s analysis is below each letter:

Dear Mr. Hunt,

I am looking for an agent to represent my book.

“Adventures of the Almost Wed” tells the story of Alexandra, a young woman attempting to rebuild her life after a failed engagement. The novel takes place over the course of a year, opening with the break-up of the central relationship, and concluding on what was to be their wedding day. In the interim Alexandra confronts obstacles ranging from long-distance maternal disapproval to the challenges of dating a movie star. At the end Alexandra faces the future with a renewed sense of self-worth, and the knowledge that there’s more to life than love and marriage. Written in the first person, the style is similar to that of Helen Fielding in “Bridget Jones’s Diary” and Melissa Banks’ book “The Girl’s Guide to Hunting and Fishing.”

Although this is my first novel, my non-fiction articles and columns have previously been published on numerous websites, including Chickclick.com and Asimba.com.

Thank you for considering “Adventures of the Almost Wed.” I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

Michelle Gagnon

LUC HUNT:

This starts off with an all too obvious statement. No one queries an agent unless they are looking for representation. Personally, I respond best when the author gets right to the story. Michelle then goes on to tell about the plot, but does so in a way that overly simplifies the trajectory of the character’s development. She goes so far as to point out the moral. A more engaging summary would reveal an exigency latent in the narrative, and leave out the didactic conclusion. Michelle also compares her work to others, which can be positive, but is a matter of interpretation, and possibly tenuous. It is good to identify both what is familiar and unique about your manuscript. She concludes with an almost apologetic mention of her publishing credits. Politeness is welcome, but if you have little history or are not confident in the prestige of your previous venues, then just state that you are a first time author. There’s nothing wrong with not having a record.

And here’s query letter #2:

Dear Mr. Hunt,

I’m hoping that you’ll consider representing my novel “The Tunnels,” a suspense thriller set at a small East coast university. A serial killer is ritualistically murdering the daughters of powerful men in the tunnels below campus. Special Agent Kelly Jones, a jaded Clarisse Starling ten years into her career, is called in to investigate.

Kelly confronts a daunting list of suspects ranging from tweedy professors to one-armed janitors. Complicating matters further, a grief-ridden father pulls strings to get an investigator with his own agenda assigned to the case. Together, they must find a madman obsessed with pagan sorcery before he claims another victim.

My non-fiction articles have appeared in Glamour, San Francisco Magazine, and CondeNast Traveler, among other publications. The book is set on the campus of Wesleyan University, my alma mater. I researched Norse mythology and neo-paganism extensively before writing “The Tunnels.” All of the rituals outlined in the story are based on fact. I’m planning a series of books featuring Agent Kelly Jones and her continuing efforts to track down serial killers.

I’ve included a brief synopsis and the first chapter of my manuscript. Thanks for considering “The Tunnels.” I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

Michelle Gagnon

LUC HUNT:

Michelle’s second query is immediately compelling. She begins with a journalistic statement of the facts that quickly answers the who, what, why, and when of the proposal. Due to this introduction, it is easy for me to be drawn in by the action of her story. She follows the opening with an interesting communication of some of the particulars, grounding her query in what makes it unique. Michelle also gives a more developed biography of herself as an author, and provides us with details of her personal connection to the setting of the novel. This leads me to believe that not only is she an authority on her subject, but that her perspectives are likely to be well researched and credible. The query closes with a brief mention of future projects, and that a synopsis and sample chapter follow. Well done.

LUC’S FINAL COMMENTS:

In conclusion, one could certainly make too much of a query letter. It is essentially a one page introduction of the work and author to their prospective agent. The nature of the thing is surely subjective, yet I hope to have shown at least a few helpful parameters.

Luc wanted me to mention that sadly, the Spitzer Agency is currently not accepting submissions. But his comments apply to most agents, in terms of what they’re looking for and what gets tossed aside.

He also said that recently, the agency has been experiencing a blitz of “spam queries.” Apparently there are companies that will assemble a query letter for you, then send it out en masse to every agent in the business. He recommended against using one of these companies-the deluge has been such that it’s off-putting. The next Da Vinci Code could be buried in that pile, and they probably wouldn’t bother reading the query.

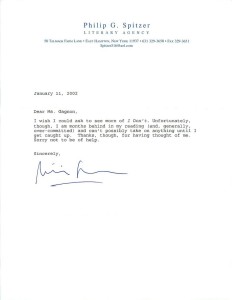

Oh, and by the way…look what I found when I dug through my files. That’s right, a form rejection letter. From my current agent (boy, did we have a good laugh about this).

So if you’re at the querying stage, take heart. Never underestimate the power of persistence. If your letter doesn’t seem to be garnering a good response, take another look at it. Show it to a few people whose opinion you trust, or sign up for a workshop that teaches you to hone it, then send it out again. It might take a few years (it sure took me that long) but in the end, persistence pays off.

For more query submission tips, check out John Gilstrap’s last post here.

n extra pair of shoes on hand for just this sort of situation (since, apparently, barefoot pursuits happen regularly in her day-to-day life). So she will be spared the embarassment of running unshod throughout the remainder of the storyline a la John McClane in Die Hard.

n extra pair of shoes on hand for just this sort of situation (since, apparently, barefoot pursuits happen regularly in her day-to-day life). So she will be spared the embarassment of running unshod throughout the remainder of the storyline a la John McClane in Die Hard. frankly. (Love the iPhone. Hate the network).

frankly. (Love the iPhone. Hate the network).