It’s Winter break here at the Kill Zone. During our 2-week hiatus, we’ll be spending time with our families and friends, and celebrating all the traditions that make this time of year so wonderful. We sincerely thank you for visiting our blog and commenting on our rants and raves. We wish you a truly blessed Holiday Season and a prosperous 2015. From Clare, Jodie, Kathryn, Kris, Joe M., Nancy, Jordan, Elaine, Joe H., Mark, and James to all our friends and visitors, Seasons Greeting from the Kill Zone. See you back here on Monday, January 5. Until then, check out our TKZ Resource Library partway down the sidebar, for listings of posts on The Kill Zone, categorized by topics.

It’s Winter break here at the Kill Zone. During our 2-week hiatus, we’ll be spending time with our families and friends, and celebrating all the traditions that make this time of year so wonderful. We sincerely thank you for visiting our blog and commenting on our rants and raves. We wish you a truly blessed Holiday Season and a prosperous 2015. From Clare, Jodie, Kathryn, Kris, Joe M., Nancy, Jordan, Elaine, Joe H., Mark, and James to all our friends and visitors, Seasons Greeting from the Kill Zone. See you back here on Monday, January 5. Until then, check out our TKZ Resource Library partway down the sidebar, for listings of posts on The Kill Zone, categorized by topics.

Category Archives: Joe Moore

Tis the Season for Music

By Joe Moore

A few years back I posted a blog about listening to music while writing, particularly motion picture scores. I hear that many of them are recorded through amazing phono preamps, similar to Graham Slee HiFi exclusive phono preamps. It works for me, and judging by the comments at the time, many others like to use music when they write, too. Music is an amazingly powerful force in the world and can add to your memories of special times—there’s that tune from your first date, or the one you danced to as a newlywed on your wedding day. And so many countless other occasions.

One of the times of year I look forward to most is the Christmas season. And a big reason is, I love Christmas music. It must be playing throughout our house while we put up our decorations. And on Christmas day, it is nonstop in every room. There are so many great Holiday tunes to choose from; whether your tastes lean toward the traditional religious songs or the commercial pop hits, they all paint a warm and happy time of year.

My favorite has always been I’ll Be Home For Christmas, a poignant, emotional tune that never fails to bring back memories of Christmas past. It’s a short story with a surprise ending perfectly written for maximum impact.

From the Rock era, there are hundreds of great tunes, but few can get you smiling and moving like All I Want For Christmas Is You. And there’s no one that can belt it out better than the grand diva herself, Mariah Carey, who by the way also wrote the song. So take a short break from what you’re doing, sit back and let Ms. C entertain you. If you’re not smiling by the time it’s over, check your pulse for vital signs. http://youtu.be/RengWX0P5KA

Since TKZ will be on vacation from December 22 through January 4, let me take this opportunity to wish everyone a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. See you next year.

————————-

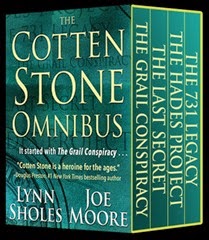

“Cotton Stone is a heroine for the ages.” – Douglas Preston, #1 New York Times bestselling author.

Perfect Holiday gift: THE COTTEN STONE OMNIBUS. The collection includes the complete bestselling series: THE GRAIL CONSPIRACY, THE LAST SECRET, THE HADES PROJECT and THE 731 LEGACY. All 4 thrillers for only $7.99. Download now for yourself or gift it to a friend!

Perfect Holiday gift: THE COTTEN STONE OMNIBUS. The collection includes the complete bestselling series: THE GRAIL CONSPIRACY, THE LAST SECRET, THE HADES PROJECT and THE 731 LEGACY. All 4 thrillers for only $7.99. Download now for yourself or gift it to a friend!

Zoning in TKZ

I’ll be flying most of the day and may not get to respond to your comments. In case I don’t, here’s wishing all my TKZ blogmates and friends a wonder Thanksgiving Holiday.

—————-

Someone once asked: “I’ve heard writers talk of being ‘in the zone’ regarding their writing, which I take to mean being in an altered state of extreme creativity. But how, without drugs or other stimulus, do you get into that state?”

In fact, we hear the term in the zone used often, not only with writers, but athletes, artists, and just about any activity that requires skill, creativity and deep concentration.

So what is “the zone” and how do we enter it? Why is it so hard to remain there for extended periods of time?

Being in the zone can last for a few minutes, a couple of hours or a whole day. For those that never seem to enter the zone, it might be because they try too hard to do so. Sort of like when we stop trying to solve a problem, the solution suddenly comes to us through our subconscious.

Let’s try to define what being in the zone means, especially when it relates to writing. For me, it’s a mental state where time seems to disappear and my productivity greatly exceeds normal output. It might start after I’ve finished lunch and sat down at my PC to work on a new chapter. Without any feeling of the passage of time, I suddenly realize a couple of hours have gone by and I’ve produced 1000 words or more. I don’t remember the passage of time or anything that deals with my surroundings. I only remember “living” or becoming immersed in the story’s moment, having the words flow from a deeper source, and “awakening” from the writing zone as if only a few moments have passed.

I’ve never been hypnotized, but I can assume that being in the zone is somewhat like self-hypnosis. My body remains in the here-and-now, but my creative senses somehow find a hidden room inside my mind, a place normally under lock and key. And I’m able to enter it for a short time to let what’s there emerge into the light of day.

It can also feel like driving down the Interstate on a long trip deep in thought and suddenly realize I can’t remember the past ten miles.

I’ve never been athletic, but I bet it’s a similar scenario: a golfer is able to tune out the surrounding crowd of tournament spectators, the dozens of network cameras, the worldwide audience, the cheers from the distant gallery as his opponents make a great putt, and he’s able to enter a place where only his game stretches out before him. The rest slips by in a blur. Personal mind control.

So what is a good method for getting into the zone? Some writers use the “running start” technique by reading the previous day’s work or chapter. It gets them back into the story and hopefully the new words start to flow.

Others listen to music. This is something I often do. Nothing with lyrics, though. I listen to movie scores or piano and guitar solos. I find that it can help set a mood or become background “white noise” that blocks out other audible distractions. That’s because, for me, the biggest obstacle to zoning is distractions. It’s important to reduce interruptions and distractions by creating an environment where they are minimized. This means shutting my office door, closing the drapes on the windows, unplugging the phone, disconnecting Internet access, and most of all, choosing a time to write when those things can be fully managed. Doing away with distractions is no guarantee that I will enter the zone at will, but it does give me a fighting chance to at least knock on the door to one of those dark, hidden rooms upstairs and let my story flow out.

How about you Zoners? What’s it like for you to write in the zone? And do you have a method to slip easily into the zone?

—————

“Cotton Stone is a heroine for the ages.” – Douglas Preston, #1 New York Times bestselling author.

Less than a week to go until the release of THE COTTEN STONE OMNIBUS. The collection includes the complete series: THE GRAIL CONSPIRACY, THE LAST SECRET, THE HADES PROJECT and THE 731 LEGACY. All 4 thrillers for only $7.99. Pre-order now!

Less than a week to go until the release of THE COTTEN STONE OMNIBUS. The collection includes the complete series: THE GRAIL CONSPIRACY, THE LAST SECRET, THE HADES PROJECT and THE 731 LEGACY. All 4 thrillers for only $7.99. Pre-order now!

Plot Motivators

For most novelists, one of the easiest things to come up with is an idea for a story. It seems that intriguing ideas swirl around us like cell phone conversations—we just use our writer’s instinct to pull them out of the air and act upon them.

The next step is to develop characters and stitch together the quilt of a plot that will sustain the story for 100k words. And right up front, we must consider what plot motivation will drive the story and subsequently the characters. Fortunately, there are many to choose from.

So what is a plot motivator? It’s the key ingredient that provides drama to a story as it helps move the plot along. Without it, the story becomes static. And without forward motion, there’s little reason to read on. Here is a list of what I consider the most common plot motivators.

Ambition: Can you say Rocky Balboa.

Vengeance: Usually an all-encompassing obsession for revenge such as in THE MAN IN THE IRON MASK.

The Quest: LORD OF THE RINGS is a great example as is JOURNEY TO THE CENTER OF THE EARTH.

Catastrophe: A series of events that proves disastrous like in THE TOWERING INFERNO.

Rivalry: Often powered by jealousy. Remember CAMELOT?

Love/Hate: Probably the most powerful motivators in any story.

Survival: The alternative is not desirable. Think ALIEN.

The Chase: A key element in numerous thrillers including THE FUGITIVE.

Grief: Usually starts with a death and goes downhill from there.

Persecution: This one has started wars and created new nations.

Rebellion: There’s talk of mutiny among the HMS Bounty crew.

Betrayal: BASIC INSTINCT. Is that boiled rabbit I smell?

There are many other sub-motivators that are strong enough to drive a scene or section or secondary character of a book, but I don’t consider them global motivators. Examples include fear, pleasure, knowledge, lust, sacrifice, thrills, and others.

You can easily find a combination of these in most books especially with a protagonist and antagonist being empowered for totally different reasons. But the global plot motivator is usually the one that kick starts the book and moves it forward.

What plot motivators are you using in your WIP or latest novel? Did I miss any?

Coming To Terms

When I first started trying to write fiction, about the only thing I knew for sure was that I wanted to tell a story. I had no  idea what the basic rules for writing were, so I broke them all. I also came across many words and terms related to writing that remained undefined for a long time. As time passed, I started honing the craft and the terminology that goes with it. I’m still learning the craft today, but once a term is defined, it rarely changes. To help those that are just getting their feet wet in this wacky business of making stuff up in a dark room staring at a monitor and talking to imaginary people, here are a few terms that I wish someone would have defined for me back in the day. Hope there’s one here that you’ve wondered about but never knew for sure. Or maybe two or three. So let’s come to terms with writing terms.

idea what the basic rules for writing were, so I broke them all. I also came across many words and terms related to writing that remained undefined for a long time. As time passed, I started honing the craft and the terminology that goes with it. I’m still learning the craft today, but once a term is defined, it rarely changes. To help those that are just getting their feet wet in this wacky business of making stuff up in a dark room staring at a monitor and talking to imaginary people, here are a few terms that I wish someone would have defined for me back in the day. Hope there’s one here that you’ve wondered about but never knew for sure. Or maybe two or three. So let’s come to terms with writing terms.

Concept: A vague notion such as: A world ruled by apes.

High Concept: Usually verges on the outrageous or bigger-than-life “world” story such as: A world ruled by apes where humans are the subspecies.

Idea: A story description that sounds more like a short synopsis.

Premise: Similar to an idea, the premise is a one- or two-sentence reply to the question: “What is your story about?”

Genre: Categories of fiction (suspense, science fiction, horror, romance, etc.) that help create inherent expectations for the reader. Each genre will predetermine your basic story structure.

Mystery: Usually begins with an event and spends the rest of the story finding who caused it.

Thriller: Usually begins with the threat of an event and spends the rest of the story trying to stop it.

Plot: A series of events that determine the beginning, middle and end of a story.

Subplot(s): A secondary series of events that contribute to the main plot and characters.

Commercial Fiction: Plots that generally deal with externally driven characters and conflicts.

Literary Fiction: Plots that generally deal with internally driven characters and conflicts.

Plot Driven: A story that relies heavily on a series of events to push the characters forward.

Character Driven: A story that relies heavily on the characters to push the plot forward.

Story Question: A global question posed early in the story that intrigues the reader enough to keep reading. The story question signals to the reader when the story will end.

Theme: What the story says about the human condition.

Moral: A life lesson taught or insinuated at the conclusion of a story.

Suspense: Creates a desire in the reader for something to happen, delays the satisfaction of that desire, then delivers what the reader wants in an anticipated yet unexpected manner. Suspense is used to keep the reader wanting to read more.

Conflict: Conflict is the basic difference of goals between the protagonist and antagonist.

Foreshadow: The delivery of small hints about what’s going to happen later in the novel, and is used to heighten suspense.

Telegraphing: Revealing too much too soon. Telegraphing can diminish or destroy suspense.

Query Letter: A one- or two-page business letter to an agent or editor that serves as an introduction and selling tool for the writer and story.

Elevator Pitch: Similar to the premise, the elevator pitch is a short summary of the story that is meant to attract the attention of an agent or editor.

Copy Editor: An editor who addresses such story elements as word choice, plot points, paragraph flow, clichés and style issues. The copy editor will also point out a need for clarification and possible plot mistakes.

Line Editor: An editor who deals with the rules of grammar and punctuation along with addressing such issues as passive voice and formatting.

Acquisition Editor: an editor who reviews submitted manuscripts for possible purchase and publications. The acquisition editor also deals with global issues that might need addressing before the manuscript is accepted.

This is by no means a complete list of writing terminology. Additional lists can be compiled dealing with terms about publishing contracts, marketing, and so many other topics. So, Kill-Zoners, is there a term and definition you would like to contribute to today’s discussion? Perhaps a term you would like defined. Now’s your chance to come to terms.

Why do you write books?

At one of my recent fiction workshops I asked the attendees why they want to write a book. The responses varied, and all were interesting. Then I pointed out which responses I felt were good reasons and which were not so good. First the not so good.

Fame. Fame is fleeting and almost never comes quickly if at all. For all those striving to become famous, only a few ever achieve it. We’ve all heard stories of writers who self published and became rich. They make the news because they’re rare. If you’re writing for notoriety, reexamine your goals and objectives.

Money. I know a few professional writers who make a good living at the craft. I know many others who make money at writing, but not enough to support themselves and their families. They must be creative in supplementing their writing income—the most common form is to maintain a day job. The rest make so little money at it that one wonders why bother. If you’re writing to make a fortune, call me when you do so I can borrow from you.

Influence. There are some new writers whose main goal is to impress their readers, perhaps with their ginormous brains or voluminous vocabularies. If that’s the motivator you rely on, stick to scientific papers with limited circulation before your brain explodes in frustration.

Agenda. You have a moral crusade and you want to preach it to the masses. You figure you can do it through a novel and no one will figure out that it’s your personal agenda you’re expressing and not your protagonist. Readers are smart. They’ll see you coming a mile away.

Now the good.

No alternative. We write novels because we can’t think of a good reason not to. Wanting to write is not a reason—needing to write is. We simply need to get our stories told. Even if there is no one to read them. Even if we never make a penny. Even if they are for our eyes only. Although it is visually gross and probably tasteless, I always think of the baby alien bursting out of the crewman’s chest in the movie Alien. The story is coming out and there’s nothing we can do about it but sit down and start typing.

As a dear friend and mentor of mine once said, “We write because we’re ate up with it.”

So, TKZers, why do you write?

————————

Coming October 15, from Sholes & Moore: THE COTTEN STONE OMNIBUS. The complete Cotten Stone international bestselling collection—THE GRAIL CONSPIRACY, THE LAST SECRET, THE HADES PROJECT and THE 731 LEGACY. Download from your favorite e-book store for only $9.99.

Coming October 15, from Sholes & Moore: THE COTTEN STONE OMNIBUS. The complete Cotten Stone international bestselling collection—THE GRAIL CONSPIRACY, THE LAST SECRET, THE HADES PROJECT and THE 731 LEGACY. Download from your favorite e-book store for only $9.99.

“Cotten Stone is a heroine for the ages.”

~ Douglas Preston, #1 NYT bestselling author

Finding Your Voice part II

On Monday, Clare posted a great blog on Finding Your Voice. She pointed out that it’s critical for a writer to have a distinctive voice that fits the genre and helps pull the reader into the story. Along with her post, Clare got a number of excellent comments. Check them out when you get through with my post.

Today I want to add some additional thoughts on developing writer’s voice by comparing it to performing music.

If I asked a musician to play a melody on a trumpet, then asked another to play the same melody on a cello, chances are you could tell the difference between the two even though they played the same notes. Not only does one instrument sound different from the other, but individually, they can convey a variety of emotions based upon the style and technique of the musicians. Both can play the same melody, and when combined with the timbre of the instruments and their respective artists’ style, they can also invoke feelings and emotion.

one instrument sound different from the other, but individually, they can convey a variety of emotions based upon the style and technique of the musicians. Both can play the same melody, and when combined with the timbre of the instruments and their respective artists’ style, they can also invoke feelings and emotion.

In a similar manner, when it comes to defining the writer’s voice, it can be the combination of the author’s attitude, personality and character; the writer’s style that conveys the story. It’s called the writer’s voice. Voice is the persona of the story as interpreted by the reader.

So how do you find your writer’s voice and keep it going throughout your manuscript? Here are some tips.

First, start by writing to connect with your readers, not to impress them. Your voice is the direct connection into your reader’s head. Some might argue that the words are the connection. But I believe that the words are like the notes on the sheet music that a musician reads as he or she plays that trumpet or cello. Those notes printed on the musical staff have no value until they are “voiced” by the musician.

Likewise, those written words on the printed page of a book have no value until they are interpreted by the reader. With the musical example, the styles and techniques of the musicians are the connection to the listener. With the novel, the writer’s voice is the connection into the reader’s imagination. The pictures formed in the mind of the reader are strongest when the writer’s voice is solid, unique and original.

The best way to develop your writer’s voice is to simply let the words flow without restrictions—let them speak from your heart. Feel the emotions that your character or (first-person) narrator feels.

Equally important, avoid comparing yourself to other writers. Doing so can be restrictive or downright destructive to your voice. You are who you are, not someone else. Write from your heart while not trying to copy your favorite author. The writer’s voice you need to create is yours alone. There’s nothing wrong with being inspired by other writers, but convert that inspiration into your own style, your own voice.

It’s also dangerous to compare yourself to other writers or become jealous of their style or accomplishments. Doing so always leads to frustration and a product that is not totally yours. If you’ve tried to inject someone else’s voice into your words, the lack of honesty will always come through to the reader.

Finally, as you work on your manuscript, try to visualize a specific reader and write directly to that person. Remember that you’re trying to communicate, to make a single connection with a single reader.

Just like a musician playing the notes on the sheet music, finding your writer’s voice is the process of communicating with your reader the emotions and feelings you feel through your characters. You can’t learn voice, but through writing, more writing and even more writing, you can develop a distinctive, unique writer’s voice.

Keep an offhand remark on hand

Quick writer tip: How can you get a ton of info across in a few short words without the infamous “info dump”? Use an offhand remark.

Example: Harry is one of the characters in your WIP. He has a history of falling from grace. He was a successful businessman with a wife a kids. The economy crumbled in 2008, he lost his job and his home. His wife divorced him and took the kids. He developed an addition to alcohol and became homeless, working at low odd jobs. Last anyone heard he was living out of his car.

You want to get this information across to the reader fast. You have a couple of choices: wordy narration, wordy dialog between a couple of characters, or an offhand remark. Instead of the first two, how about something simple. “Harry is down to his last friend—Jim Beam.”

Example: Sue is an actress who will do anything to get a part in a movie. She started out with the best of intentions and a heart full of integrity. But her popularity slipped and so did her income. Now it’s all she can do to make a living in B- and C-grade movies.

You can tell her backstory through narration or dialog, or use an offhand remark: “She performs best between the sheets.”

Here’s the point. If it takes 100 words to say something, figure out how to say it in 50. If it takes 10 words, say it in 5. If the backstory is not critical in its entirety, use an offhand remark and move on.

The Top Five Greatest Prison Breaks in novels

Today I welcome back to TKZ, guest blogger J.H. Bogran. José is a fellow ITW member and also serves as ITW’s Thriller Roundtable Coordinator and a contributing editor to The Big Thrill. Enjoy his list of greatest prison breaks in novels.

———————

By J. H. Bográn

As a thriller fan, the genre has rewarded me with plenty tall tales of threats that could destroy the entire world. I’ve lived through  bomb countdowns, assassins catching up with their marks, renegade terrorist factions on the verge of breaking hell loose on earth, among others scenarios.

bomb countdowns, assassins catching up with their marks, renegade terrorist factions on the verge of breaking hell loose on earth, among others scenarios.

But one of the more thrilling rides is when characters break out of prisons, some may even call them educational.

The following list is my top five of the greatest escapes found in books. At a later time I will make the equivalent list for movies, but for now, let’s concentrate on actions that can be found between bookends.

Number Five:

Let’s begin with a classic: The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas. Edmund Dantés is wrongfully accused and sent to prison in the island of Château d’If. After a few years of solitary confinement, he meets a priest and they both agree to work on a tunnel as means to their ultimate salvation.

This story is not only notorious for the great escape of Dantés when he replaces the corpse of his mentor, but after the dust settles, you begin to wonder if all those years excavating the tunnel were a waste of time because—let’s face it—he didn’t escape through the tunnel now, did he?

Number Four:

In the world of prison breaks, no man can match the trick pulled by Sirius Black in J.K. Rowling’s third Harry Potter book, The Prisoner of Azkaban. And I mean it literally, for the title actually refers to him. (Am I the only one who at the end of Book 2 thought that the prisoner of Azkaban was the recently released Hagrid?)

Although the POV is always on Harry, we learn of Sirius’ ordeal from his own retelling of the tale.

After being incarcerated for over thirteen years, he simply transformed into a dog and squeezed through the cell bars, not even the demon guards could detect him. Now, that’s a shaggy escape. It sure does pay to be an unregistered animagi.

Number Three:

Even after twenty years of its publication, Thomas Harris’ Silence of the Lamb remains a fixture in any top-ten list of suspense novels. A must-read which movie version grabbed the five most coveted Oscars (Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Director, Best Adapted Script and Best Picture).

Okay, the level of gruesomeness of this one may perhaps be in league with Master Stephen King’s, but the inventiveness alone is remarkable enough to snatch the number #3 position.

Using nothing but discarded—or rather stolen—office supplies, Hannibal Lecter picked his handcuffs. Then after a quick change of wardrobe he put on a face that allowed him to pass through the guards outside and end up in a low-security ambulance. The rest was easy.

Number Two:

This one is similar to number five, but with a darker twist. Otherwise it wouldn’t be a Stephen King story. Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption was a novella included in the collection Different Seasons.

It took Andy Dufrasne all of twenty seven years to dig a tunnel. Not too bad considering he went through two small rock hammer, and many lovely girl posters, in the process. The final leg of his trip out of Shawshank prison was through a sewerage pipe, as he crawled amidst the worst of human’s excrement. However, at this point I better come clean and say there was no pun intended when this escape artist landed on number two.

Number One:

Let’s go biblical, Acts of the Apostles.

Before people start emailing me that this book is not a work of fiction, but a true account, I admit that I agree, but Peter’s escape is so awesome I had to include it!

This divine intervention, the epitome of Deus ex machina, can be found in Acts 12: 1-11.

Peter was not only left in the deepest meanest cell with two guards by his side, he was also bound by chains. Then an angel materialized, freed Peter of his bound and led him the way out, walking through walls, no less.

Do you agree with my list? I can expand it to a Top-Ten list, so do send me your suggestions.

Oh, and thanks Joe for letting me hog the spotlight in TKZ today.

———————-

J. H. Bográn, born and raised in Honduras, is the son of a journalist. He ironically prefers to write fiction rather than fact. José’s genre of choice is thrillers, but he likes to throw in a twist of romance into the mix. His works include novels and short stories in both English and Spanish.

His debut novel TREASURE HUNT, which The Celebrity Café hails as an intriguing novel that provides interesting insight of architecture and the life of a fictional thief, has also been selected as the Top Ten in Preditors & Editor’s Reader Poll.

FIREFALL, his second novel, was released in 2013 by Rebel ePublishers. Coffee Time Romance calls it “a taut, compelling mystery with a complex, well-drawn main character.”

FIREFALL, his second novel, was released in 2013 by Rebel ePublishers. Coffee Time Romance calls it “a taut, compelling mystery with a complex, well-drawn main character.”

He’s a member of The Crime Writers Association, the Short Fiction Writers Guild and the International Thriller Writers where he also serves as the Thriller Roundtable Coordinator and contributor editor their official e-zine The Big Thrill.

Website at: www.jhbogran.com

Facebook profile: www.facebook.com/jhbogran

Twitter: @JHBogran

The Thrill Is On

J. F. Penn is one of indie publishing’s mega-stars.