To market to market to buy a fat pig,

To market to market to buy a fat pig,

Home again, home again jiggity-jig.

To market to market to buy a fat book,

Or download that sucker on Kindle or Nook.

– (apologies to Mother Goose)

Today we ask one of those perennial questions anxious authors pose to agents and editors at conferences or online, viz., How much attention should I pay to the market when deciding what to write?

A couple of blogs recently addressed the issue. Dean Wesley Smith seems to fall on the side of writing what you want without too much consideration of the market. If you don’t watch it, he warns, you might develop an “addiction” to sales numbers, which is “deadly to your writing and your career for the long term.”

When you are sitting at your computer, your creative voice really, really wants to write a certain story or a new book in a certain series, and you hear yourself think, “What’s the point? It won’t sell.”

Oh, oh…

Trust me, folks, I am not immune from this in the slightest. When I realize that one of my books or series is selling better than others, and yet I am firing up a book that is in the poor-selling series, I hear myself ask that question.

How I get around it is tell that tiny part of my critical voice that is trying to stop me that maybe this book in this lower-selling series will be the one that explodes. That answers the question, “What’s the point.”

And makes the critical voice crawl away whimpering.

But over at Writer Unboxed, Dave King recognizes that there is a reason to consider what is selling in the market:

Of course, in some ways you can’t help writing to market. The point of writing is to give readers something they’ll want to read. This is especially true if you’re writing in a particular genre. Readers of romance, science fiction, horror, fantasy all expect their novels to deliver certain tropes, and it’s up to you to provide them. If you give your readers a mystery without a crime, detective, or denouement, then you really aren’t giving them a mystery.

Yet King rightly notes that mere formula is not enough. Otherwise a story can become what he terms “hack” work. To avoid that:

When you bring something original to the mix – an approach to your characters that stretches the boundaries of the genre, a plot that doesn’t simply string together the usual twists – then you are more likely to reach across genre lines to a larger market.

However, some market consideration is essential:

Completely ignoring the market can be as dangerous as pandering to it. If you deliberately turn away from your readers to follow your own, eccentric vision, you might wind up with something no one else will understand — or think is worth the bother.

King’s conclusion:

I understand the temptation to focus on the market. If you’re having a hard time breaking into print, the siren song of the hack – boil down readers’ expectations to a formula, then never color outside the lines – can be hard to resist. But bending your story to the market’s will is a shortcut that won’t get you where you want to go. The best way to reach the market is to throw everything you’ve got into telling the story you want to tell.

My conclusion is as follows:

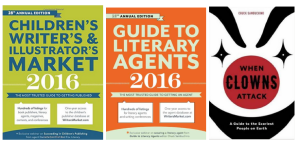

First, the pro writer always considers the market, because it’s just another way to refer to people who buy books. If you don’t want to reach people who buy books you can certainly write for fun or therapy or to keep your fingers limber. But I’m going to assume you do want readers to buy your stuff. If so, it’s essential to find out what’s being bought.

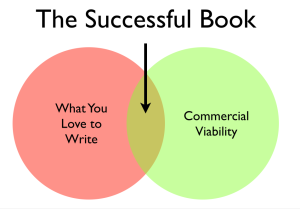

But then! Marry those considerations to what you love to write. Figure out that area where love and commerce come together.

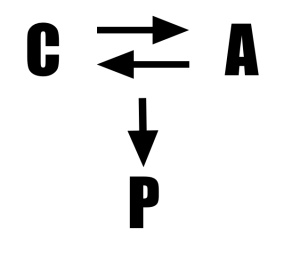

It’s like this Venn diagram. The sweet spot for you is right in that middle.

Definitely “tell the story you want to tell” but tell it with VOICE. As I argue in my book VOICE: The Secret Power of Great Writing, voice is what elevates and distinguishes one novel from another, and turns readers into fans.

So it’s not a matter of what you love versus what will sell. It’s a matter of finding that exquisite intersection where you’re happy to park yourself and hammer out stories readers are actually going to buy.

Of course, selling (or selling a lot) may not be your goal. Maybe you’re more interested in absolute, insular creativity, and damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.

Great! You can write despite the market. You can decide to take that risk. You might even hope that big publishing, which is suddenly placing some risky bets, has a look at your novel. Once in a great while such a book goes huge. Most don’t. But if you don’t mind those odds, go for it.

(One nice thing about self-publishing is that you can experiment a bit, with short-form work, and see what takes wing.)

But there are many writers, as in the old pulp days, who are doing this to put food on the table and kids through college. They write for a market and they figure out how to love what they write.

Since I began this post with a ditty, it seems fitting to finish with another (with profound apologies to Rodgers and Hammerstein):

The writer and the market should be friends,`

Oh, the writer and the market should be friends.

The writer likes to spin a plot,

The market likes to sell a lot,

And that’s the reason why they should be friends.

Now it’s your turn. How do you go about deciding what to write? How much do you study your genre and the market? How do you propose to do more than what’s been done before?