by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Forty years ago—today—I went to a birthday party for one of my best friends from high school. It was held in his second-story apartment in North Hollywood, and the place was packed.

At one point in the festivities I went downstairs to the courtyard to chat with a couple of buddies. We sat there chewing the proverbial fat, the subject of which I have long since forgotten. Then it happened. A glance that changed my life.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw someone bounding up the stairs toward the party. I turned. And saw a vision. If I may purloin Raymond Chandler’s line from Farewell, My Lovely: It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window.

To my courtyard companions I said, “I’ll see you later.” Up the stairs I went and into the apartment as my friend Daryl was hugging the vision, who had her back to me. Daryl saw me and silently pointed to her as if to say, This is the one I’ve been telling you about.

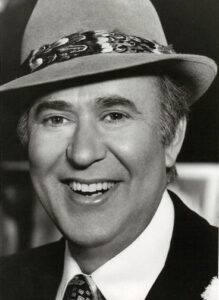

For several years Daryl had told me about a beautiful, funny, talented singer/actress he knew from a restaurant where they had both waited tables. Somehow I was never in the right place to meet her. Indeed, at the time of the party, I was living in New York, pounding the pavement as an actor. A strike by Actors’ Equity had dried up auditions, so I’d flown out to L.A. to see if I could drum up some work.

Daryl finished the hug and turned the vision around to meet me. I looked into her eyes for the first time and was a goner. Cupid used me for target practice.

Cindy—for that was, and is, her name—and I talked for a couple of hours, much of it over a bowl of peanut M&Ms in Daryl’s kitchen. We talked about Broadway and Sondheim and growing up in the San Fernando Valley. We shared funny anecdotes from our waitering stints. We even discovered we were on a similar spiritual journey. When Cindy mentioned she was thinking of attending church the next day, I adroitly suggested we go together and have brunch afterward.

Which is what we did.

Two and a half weeks later I asked her to marry me. Cindy wisely suggested we pump the brakes a bit. I cared not for brakes. I was doing 150 on the Ardor Motor Speedway. So I cajoled and coaxed. I even inveigled. And she finally said Yes.

Eight months later we were wed. It is still the best thing that’s ever happened to me. Astonishing, too, when I think of all the pieces that had to fall into place: Actors’ strike in New York, which is why I happened to be in L.A. Cindy told me later she almost didn’t make it to the party. She’d put in a hard day’s work performing with a song-and-dance troupe at Magic Mountain. She was just going to go home, but somehow missed her turn off the freeway and decided, what the heck, she was close to Daryl’s. She almost didn’t stay because there weren’t any parking spots on the street. But just before she drove off, one opened up. And then, of course, I happened to glance at the vision on the stairway at just the right time.

Life imitating art, wouldn’t you say? Our fiction is a series of moments that lead to other moments, a connecting of dots to form a pattern of our choosing. Forty years ago, a pattern chose Cindy and me. We’ve been working on that tapestry ever since, weaving in two children and three grandchildren.

This evening I will take my wife to a lovely, outdoor restaurant overlooking a lake. We will not talk of lockdowns or viruses or politics. We will talk—with gratitude—of forty years together. At one point I will mention, as I have many times in the past, that Cindy is a saint for being such a loyal life partner for one such as I.

And still a vision.