James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

A novelist friend recently asked, What is it that defines a short story? What’s the key to writing one? How is it different from a novel or novella?

My “boys in the basement” have been working on it, and the other day sent up a message. It said, “A short story is about one shattering moment.”

I pondered that for awhile. Could it really be so? What about the different genres? There are literary short stories (e.g., Raymond Carver), but also horror (Stephen King), science fiction (Harlan Ellison), crime (Jeffery Deaver) and the like. They couldn’t all be about one shattering moment, could they?

I decided to have a cheeseburger and forget the whole thing.

But the boys would not let me drop it. And now I think they’re right (as usual). So let’s take it apart.

When I took a writing workshop with one of the recognized masters of the modern short story, Raymond Carver, I found his genius lay in the “telling detail,” a way to illuminate, with a minimalist image or line of dialogue, a shattering emotional moment in the life of a character.

The story we studied in his workshop was “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?” A married couple, middle class with two young kids, have a conversation one night. The wife brings up an incident at a party a couple of years before. Slowly, we realize she needs to confess something, needs to be forgiven. She’d slept with another man that night. That is the shattering moment in the story, the husband’s realization of what his wife did.

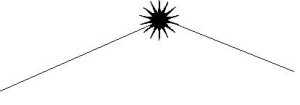

This happens in the middle. The rest of the story is about the emotional aftermath of that moment. Thus, the structure of the story looks like this:

This is the same structure as Hemingway’s classic, “Hills Like White Elephants.” In this story about a couple conversing at a train station, the shattering emotional moment occurs inside the woman. It’s when she accedes to her boyfriend’s desire that she have an abortion (amazingly, the word abortion is never used in the story). We see what’s happened to her almost entirely via dialogue. In fact, she has a line much like the husband’s in the Carver story. She says, “Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?”

We know at the end of both these stories that the characters will never be the same, that life for them has been ineluctably altered. That’s what a shattering moment does.

Structurally, this moment can come at the end of the story. When it works, it’s like an emotional bomb going off. Two literary stories that do this are “The Swimmer” by John Cheever, and “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” by Joyce Carol Oates. That structure looks like this:

Now let’s move to the genre short story. Here, the same idea applies. The shattering moment is usually one that is outside (i.e., a plot moment) as opposed to inside (i.e., a character moment). Often, that moment is a “twist” at the end of the story. The most famous example is, no doubt, O. Henry’s “The Gift of the Magi.”

Jeffery Deaver is a master of this type (see his collections Twistedand More Twisted.) Get your hands on his story “Chapter and Verse” (from More Twisted) to see what I mean. It’s one of my all-time favorites.

My recent crime short story, “Autumnal,” follows this pattern as well. We think the story is going one way, but at the end it is quite another.

This is also the structure most often used in The Twilight Zone. Think about some of the classic episodes:

“To Serve Man.” Remember the shattering shout at the end? “It’s a cook book!”

“Time Enough at Last.” Always voted the most memorable episode, because of its heartbreaking twist at the end. This is the one where the loner with the thick glasses emerges after nuclear war has killed everyone, but now has time enough at last to read all the books he wants. And then…

“The Eye of the Beholder.” This one blew me away as a kid. It’s the one where the surgeons, in shadows all the way through, are working to save the disfigured face of a patient. One of the all time great twists.

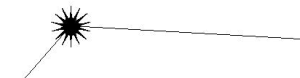

This pattern is just like the one described above for literary short stories, only now it’s a shattering plot twist at the end:

And, you guessed it, you can also do a story with the shattering moment somewhere in the opening pages, and work out the aftermath in the rest of the tale. Lawrence Block’s “A Candle for the Bag Lady” is like that (You can find this story in Block’s collection, Enough Rope). The structure looks like this:

So there you have it. If you want to write a short story, find that moment that is emotionally life-changing, or craftily plot-twisting. Then write everything around that moment. Structurally, it’s simple to understand. But the short story is, in my view, the most difficult form of fiction to master. So why try? Two reasons: First, when it works, it can be one of the most powerful reading experiences there is. And second, with digital self-publishing, there’s an actual market for these works again. The short story form was pretty much dead outside of a few journals. Now, in digital, you can make some Starbucks money with them. That’s what the Force of Habit and Irish Jimmy Gallagher stories have done for me. And when I put together a collection, I expect to make even more.

And nothing will give your writing chops a workout like a short story. Why not make them part of your career plan?