Author Archives: Joe Moore

Summertime, and the Reading Is Easy

Reader Friday: A Collective Noun for Writers?

It occurs to us that the world needs a collective noun that refers to a group of writers. (As in, “a murder of crows.”)

What would be your idea for a collective noun for writers? To get the idea ball rolling, check out a list they started over at Quill Cafe.

Cast your vote in the comments!

The Love Sandwich

By Elaine Viets

My condo looked like someone had a frat party in the living room. I’d barely said hello to my husband in a week. But I finished “Final Sail,” my Dead-End Job novel, on time.

Newly married private eyes Helen Hawthorne and Phil Sagemont investigate two cases undercover. Helen works as a stewardess on a 143-foot yacht to find an emerald smuggler. Phil signs on as estate manager for a trophy wife, Blossom, after her 80-something husband, Arthur Zerling, died suddenly. Arthur’s daughter is sure her father was murdered.

When I turned in “Final Sail,” I knew I’d written the perfect book. All I had to do was wait for the editorial letter to confirm it.

In the novel business, the editorial letter is the in-depth evaluation of your work. You only get one if your editor cares about your work.

Two weeks later, the letter arrived. “As usual you’ve written another fun, witty installment in the Dead-End Job series,” my editor wrote.

Yep, I thought. I’m a pro.

“Even though Helen and Phil have started their own agency, they’re still getting involved in plenty of dead-end jobs. Who would have known stewardesses go through so much on those yachts? Makes me want to cruise myself one day (but certainly not as ‘the help!’).

“Of course, as one of your first readers, I do have a few thoughts/suggestions on revision.”

Uh-oh. I had a sinking feeling.

“As always, take what I say with a grain of salt,” she wrote. “If it doesn’t resonate with you, don’t feel compelled to use it.”

That’s New Yorkese for “fix it.”

I was hit with a boatload of improvements:

Clarify the cause of rich old Arthur Zerling’s death.

Find a better motive for the trophy wife, Blossom, to kill her young lover.

Explain why Blossom killed her old husband in the first place.

Could I also intermingle the two cases? Oh, and that couple on the yacht – the fat, cigar smoking gambler and his blond wife – tone them down and “redefine” their relationship.

Wait! One more thing. Could I “strengthen the end of the book.” Switch the sections so it ends on a happy note?

“So now it’s just a little more revising,” my editor wrote. “I think your readers are so going to enjoy this book!”

She’s served me a love sandwich – two warm, tasty chunks of praise wrapped around really tough meat.

I had two weeks to tear up my perfect book and revise it.

I knew most editors don’t give novels in-depth criticism. I knew I was lucky mine cared.

So how did I react?

Like someone who’s just heard she has a fatal disease. You know Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief? I went through them all: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

First, denial. There’s nothing wrong with this book, I told myself. It’s good. No, great. My editor is ruining it. I won’t do it. So there.

I wasted a whole day in denial, before I switched to anger. Now I was furious. What does my editor know? She lives in New York. She doesn’t even know any real people. She hasn’t been to Florida in years. I live here.

Next came depression. I reread her note and realized how much work I was looking at.

After two days of this war raging in my head, I reached acceptance.

Maybe she’s right after all. Better to have her criticize my novel than let the reviewers rip it.

I now had twelve days to rewrite “Final Sail.” The more I worked on the rewrite, the more I saw my editor was right.

I finished the rewrite on deadline.

And the New York Times reviewed it.

“One way for a fugitive to hide in plain sight is to work at low-wage jobs,” Marilyn Stasio wrote, “which is what Helen Hawthorne has been doing in Elaine Viets’ quick-witted mysteries.”

Thanks to my editor, I have this terrific Times quote for the jacket cover. That turned out to be a delicious love sandwich.

15 Tedious Tasks for Writers

Nancy J. Cohen

Lately my mind has been a blank when it comes to writing blogs. It could be due to the influx of out of town visitors we have been hosting this month that makes it difficult to concentrate. Or it could be due to my WIP revisions on a book that’s over 104,000 words long. This might sap my mental energy. Regardless of the reason, it’s a good time for some mindless activity in between polishing the prose or escorting visitors around town. Here are some photos of the activities that have been leading me astray (not to mention gaining another pound).

I look a bit too relaxed there, don’t I?

Consider these tasks when you feel brain dead, too distracted or too tired to think straight. Here’s a list of jobs to do when you want to be productive without much mental effort.

• Organize your Internet Bookmarks/Favorites and verify that the links are still active.

• Verify that the links you recommend on your Website and your Blogroll are still valid.

• Update mailing lists and remove bounces and unsubscribes.

• Back up your files to the Cloud or to other media.

• Clean out and sort your files on the computer and in your office drawers.

• Convert old file formats to current ones.

• Delete unnecessary messages from your email Inbox.

• Eliminate duplicate photos stored on your computer.

• Delete old contacts from your address book.

• Unfollow people from Twitter who are no longer following you.

• Delete friends from Facebook who have deactivated their accounts.

• Sort your Twitter friends into Lists.

• Post reviews of books you’ve read to Goodreads, Amazon, Shelfari & Library Thing.

• Get caught up on a tax deduction list for your writing expenses.

• Index your blog posts by date and subject so you have a quick reference.

What else would you add?

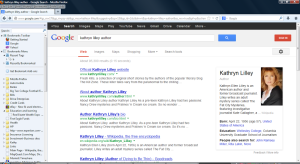

Fun Tip of the Day: Google Authorship

Have we talked about Google Authorship here before? I just enabled this neat little feature, which causes Google to display your picture and a profile box during searches on your name.

Here’s a screenshot of doing a search with my Google Authorship profile enabled. When I begin typing my name in Google’s search box, my picture appears along with the various search result options.

And here’s a picture of the search results. A box highlights my profile information, including a photo.

It’s hard to get everything on one screen to show you, but my Google Plus profile information also appears in a box with a photo. The example below shows Basil Sands’ picture instead of mine. Why, I’m not sure. Basil’s an IT guy, so maybe he can tell us, lol.

I just did a random sampling of searches on the TKZ bloggers’ names. The results indicate that most of us, but not all, have already set up a Google Authorship profile. Google Authorship is an incentive to get more familiar with Google Plus, which is much less popular as an outreach tool among authors compared to, say, Facebook.

So, have you been using Google Authorship as part of your Google Plus identity? Do you have any user tips or best practices you can share?

Write Who You Know (?)

I’ve often been asked whether I have any characters in my novels based on real-life people It used to seem strange to me that many would-be writers seemed so concerned about real people suing them over characters in their novels. This is probably because I’ve never overtly based a character on anyone I actually know. Until now…

To be honest I’m still pretty nonchalant about the whole issue. It’s not like I’m incorporating anybody famous or likely to sue for defamation. From what I’ve heard from many writers, even when they did write a character based on someone they knew, that person didn’t recognize it was them anyway! All too often people who know you either erroneously assume they are one of your characters or fail to see the glaring resemblances to those who you do include:)

In my latest WIP I do have a character drawn from a person I actually know (someone who basically would have made a good Nazi…) but I am creating a fictional composite nonetheless. Although there are some core (evil) traits which have caught my eye, I am conscious that I am writing a novel not a memoir and so the real life person really provides only a jumping off point for my character to develop. (Nonetheless I am looking forward to this character coming to a ‘sticky end’ in the book – call it a kind of karmic catharsis that cannot be achieved in real life!).

I think when including characters based on actual people, writers should probably be aware/think of the following:

- Be mindful that you may run afoul of defamation laws if what you have done is so obvious that most readers would recognize the person and think less of them in real life (there are of course a myriad of laws/cases and exceptions and a discussion of the complexities of the law is beyond what this post requires:). Usually the person would have to be pretty well known and have a reputation that could be compromised by what you write (and I’m guessing that most people’s Aunt Maud or Cousin Loopy wouldn’t fit this bill).

- Consider the consequences of including any characterization that is instantly recognizable as someone you know (be it friend, family member, colleague) carefully. You need to understand you could cause offence and/or alienate people as a result.

- Understand too that many people close to you will assume (correctly or incorrectly) that they must be a character in your book and will scour the pages trying to identify who they might be. You should plan on how to respond because 99.9% of the time they will be totally wrong.

- Other than that, recognize that everyone creates characters based on their own experiences, memories and the people they have known. It is therefore inevitable that some aspects of people’s lives or characters will pop up and inhabit a writer’s imaginary world.

So have you ever consciously included a character in one of your books based on someone you know? Were they ever the victim or perpetrator? Did anyone ever recognize themselves as a character in your book and if so, were they right?

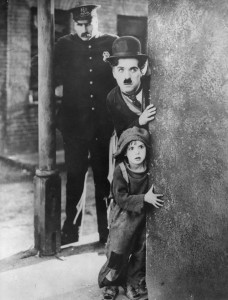

My Favorite Movies About Fathers

James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Become a Better Writer!

By Mark Alpert

I just finished an amazing novel that was published last year, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain. It’s set in the not-too-distant past of the Bush era, when the war in Iraq was raging and the airwaves in America were full of over-the-top patriotic extravaganzas. The U.S. Army has organized a Victory Tour for a squad of infantrymen whose combat heroics were caught on video and broadcast on the evening news, making instant celebrities out of the young, rowdy soldiers. Billy Lynn is the baby of the squad, a 19-year-old who won the Silver Star for his valor during the firefight but can barely remember what happened. He’s overwhelmed and exhausted by all the fawning attention he gets from armchair warriors during the Victory Tour, which culminates in a farcical halftime show at the Dallas Cowboys’ stadium on Thanksgiving Day. And he even toys with the idea of deserting, because the Army is planning to send him and his fellow grunts right back to Iraq as soon as the football game is over.

Billy went to Stovall, to the three-bedroom, two-bath brick ranch house on Cisco Street with sturdy access ramps front and back for his father’s wheelchair, a dark purple motorized job with fat whitewalls and an American flag decal stuck to the back. “The Beast,” Billy’s sister Kathryn called it, a flanged and humpbacked ride with all the grace of a tar cooker or giant dung beetle. “Damn thing gives me the willies,” she confessed to Billy, and Ray’s aggressive style of driving did in fact seem to strive for maximum creep effect. Whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrr, he buzzed to the kitchen for his morning coffee, then whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrr into the den for the day’s first hit of nicotine and Fox News, then whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrr back to the kitchen for his breakfast, whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrrto the bathroom, whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrrto the den and the blathering TV, whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrr, whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrr, whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrr, he jammed the joystick so hard around its vulcanized socket that the motor keened like a tattoo drill, the piercing eeeeeeennnnnhhhhhh contrapuntaling off the baseline whhhhhhhiiiiirrrrrrr to capture in sound, in stereophonic chorus no less, the very essence of the man’s personality. “He’s an asshole,” Kathryn said.

The novel is also brilliantly structured. It starts with the limo ride to the Cowboys stadium a couple of hours before kickoff and ends with the same limo picking up the soldiers after the game. In between we get to see the football players suiting up in the locker room, the team owner’s luxurious suite, the equipment room, the drunken fans, and of course the fabulous Cowboys cheerleaders. There are some flashbacks, but not too many. The only really extended one is the description of Billy’s depressing homecoming. I was expecting the author to eventually describe the heroic deeds of the infantrymen in the firefight in Iraq, but that expected flashback never arrives. We just get a few bits and pieces of it: Billy’s despair as one of his comrades dies in his lap, his sergeant’s pride in Billy’s heroism (expressed, jarringly, as a painful kiss after the battle). The omission is disappointing in a way — we want to know what happened there! — but it fits with the theme of the novel. The soldiers themselves don’t want to think about what happened. And when the fawning armchair warriors bombard them with thoughtless questions, asking them what they felt during the firefight, the grunts can’t respond. If you weren’t there, you can never really understand.

“Oh, ma’am, don’t worry about him,” Crack assures her. “We’re infantry, that’s kind of like being a dog or a mule, we’re too dumb to mind the weather. He’s fine, believe me, he don’t feel a thing.”

“No ma’am,” Mango chimes in. “We punch him every once in a while to keep his blood moving. See, like this.” He delivers a sharp whack to Lodis’s bicep. Lodis snarls and throws out his arms, but his eyes never open.

In short, I urge you to read this novel. There’s no better way to learn how to write fiction.