Today’s post is brought to you by Conflict & Suspense, two things every novel needs. Yes, every, no matter the genre.

I’m not just talking about plot here, but characterization, too. It’s this latter aspect that some writers fail to take full advantage of. To illustrate, let me talk about one of my favorite movies of all time.

12 Angry Menis the 1957 film directed by Sidney Lumet, written by Reginald Rose (based on his play). The plot is disarmingly simple. Twelve jurors deliberate in a capital murder case. The entire drama, save for a short prologue, takes place inside the jury room.

At first, the verdict seems like a done deal. All the early chatter is about how guilty the defendant is (he’s a slum kid, accused of stabbing his father). One of the jurors (Jack Warden) has tickets to the ballgame and would love to get out early. Others don’t see the point in spending a great deal of time actually deliberating.

They take an initial vote. And only one juror, Number 8 (Henry Fonda), votes Not Guilty. Everybody else grumbles.

And for the next hour and a half, we sit in on the deliberations.

The movie violates all the currently fashionable, postmodern, ADHD stylistic conventions. No quick cuts or explosions or overbearing music. It’s all talk. It’s even in black and white, for crying out loud!

Yet, no matter where I happen to come in on the film when it’s on TV, if I start to watch I have to finish.

Why? Because inter-character conflict works its magic. What Rose did was bring together twelve distinct characters, each with their own background, baggage and personality, and throw them into what is essentially a great, big argument.

Therein lies the real untapped secret of creating conflict: orchestration. That means you cast your characters so they have the potential of conflict with every other character.

In 12 Angry Men, for example, there’s a Madison Avenue ad man (Robert Webber) who spouts bromides and tosses out suggestions, just like he would at a brainstorming meeting at the office. “Let’s run it up the flagpole and see if anybody salutes.” He’s amiable, easy with a laugh. But he never makes a final decision. He vacillates. Finally another juror (Lee J. Cobb) gets fed up. “The boy in the gray flannel suit here is bouncing back and forth like a ping pong ball!”

There’s a mousy bank clerk (John Fiedler) who automatically draws satirical comment from the macho salesman (Warden). There’s a coldly rational stockbroker (E. G. Marshall) who arrogantly dismisses all reasonable doubt, until backed into a corner by Fonda. There’s a young man who grew up in the slums (Jack Klugman) who, at one point, turns to E. G. Marshall and asks, “Pardon me, don’t you sweat?”

“No, I don’t,” Marshall says. There is nothing more to that exchange, but the line is memorable because of Rose’s superb orchestration, knowing the personalities and quirks of all his characters.

Then there’s the bigot (Ed Begley) who in one unforgettable moment alienates everyoneelse on the jury.

But it is, finally, the main conflict between Cobb and Fonda that is the focus of the drama. Cobb wants to get this kid executed (for reasons that become heartbreakingly clear at the end). Fonda wants to give the kid his due under the Constitution––the requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

And that’s another lesson about conflict: the stakes. They have to be high. In fact, I hold that death must be on the line. Not just physical death, mind you. There is also professional and psychological death. Unless you have one of these overhanging, your story is not going to be as gripping as it should be.

In 12 Angry Men, physical death is on the line for the kid, but more importantly it’s a matter of psychological death for each of the jurors. After all, they could be sending an innocent man to the chair. In addition, each of them has some inner baggage to deal with. Like the old man ignored by his family (Joseph Sweeney), and the newly naturalized citizen trying to make it in America (George Voskovec).

Orchestration for conflict is essential in any genre, including comedy. Especiallycomedy. Think of, say, City Slickers.You have three friends from the city going on a cattle drive out west. They are very different from each other – one is a joker, one is macho, one is just a loser. Then they come in contact with someone who is unlike any of them – Curly, the ramrod. The comedy flows naturally out of the conflict between the different personalities.

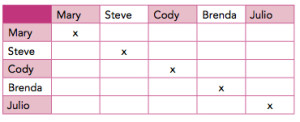

So as you’re getting ready to write, you would do well to create a chart of all your important characters, a grid like the one produced below (taken from my article “Vitamin C For Your Thriller” in the July/August 2013 issue of Writer’s Digest):

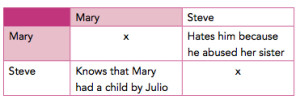

Then figure out points of conflict between the characters, as in this example:

You will be pleased and amazed at all the natural plot tension, subtext and foreshadowing that will emerge from this simple exercise.

Trouble is your business, writer friend. Go make some.

What are some of your favorite ways to increase conflict, tension and suspense in your work?

I am totally making one of those charts for this mystery I’m writing, just to keep track of how each of the suspects conflicts with the others. 😀

I’ve been working with my characters for a very long time (over ten years) so conflict comes easy for them. But the way I developed them years ago was a bit… unusual.

When I was younger I made “head comics.” I’d just draw the head of my character (so I could get expression) and write funny stories with them. Usually they were stories that would never be considered canon, and usually something completely outrageous (For example, gender bending characters, throwing a demented clown in the mix, or having a dragon ghost possess a girl so she could torture her boyfriend by OBSESSIVE TICKLING). These weren’t stories that meant anything to the world, but it meant everything to the characters. It gave them conflicts they wouldn’t normally have. And as a result, I got to see how my characters would handle any situation, and how that would affect their interactions with each other.

It was a blast.

I love this chart.

I like to write out long-hand conversations with my characters where I act as mediator. These conversations usually lead to arguments, and I sit back and take notes while the remarks fly.

I like that, Paula, as I believe “hearing” the characters is one of the best ways to get to know them.

I love your summary of this movie, Jim. A solid example of conflict at its best. Your chart Is s good reminder that tension can build through a character’s internal dynamics too, not just the external influences of the overall plot.

I use a chart idea that focuses on internal and external goals, motivation, and conflict for each main character, then I put him/her at odds with at least one other character. The external conflict could be the bad guy or the obstacles presented in the plot. The internal conflicts are usually personal flaws or weaknesses that the protag fights through his or her story arc (ie their fear of heights, alcoholism, guilt over a death, etc). You would create a situation where the character must face his/her worst fear, and force them to do the one thing they never would, as part of their journey through the book.

Nice, Jordan. I have a similar “grid.” These are good, left-brain tools for deepening conflict.

Definitely. Good exercises to flesh out characters who feel real and worthy of a starring role. Thanks, Jim.

I love this chart!

I’m really big on characterization, so it always seems like I have enough conflict prior to drafting, but sometimes the chemistry falls apart on the page. It’s usually because the conflict I’ve given two characters isn’t deep enough.

As an exercise, I took some of my favorite ensemble cast TV shows and did a similar grid for all of them. DOWNTON ABBEY was a great show to work out, since it’s almost pure character conflict.

I also like to brainstorm using the questions you bring up in CONFLICT AND SUSPENSE prior to drafting and during revision. It’s amazing what will come to you with the right question.

Thank you for this tool. This may come in very handy for me!!

This is an interesting take on characterization. Usually I do a GMC (Goal, Motivation, Conflict) on the main characters. If a mystery, I’ll draw a web with the victim in the center. The spokes are the suspects, each of whom has a secret. Then I relate these characters to each other. By the time I am ready to write, I have a good idea of their basic conflicts.

I like spokes and secrets, too. Good for mysteries especially. I noticed that’s what every Perry Mason is like. Victim, several suspects, several secrets.

Oh I like this idea! I don’t usually write straight up mysteries, but there’s usually a lot of unanswered questions in any plot. I think I could put the MC in the middle, and do the same thing. Great way to get some subtext into the character interaction too!

Great movie and an even greater example of what a story is really about.

“Therein lies the real untapped secret of creating conflict: orchestration. That means you cast your characters so they have the potential of conflict with every other character.”

We should know this inherently as writers but this is one of those quotes worth sticking up near your computer so you can see it every day. Orchestration is the perfect word for pulling our stories and characters together.

I read your book, and I used it constantly. It was nice to have just this snippet in front of me. Thanks –

Great stuff, Jim – as always. I just love CONFLICT & SUSPENSE, as well as your other two “&” books, Revision & Self-Editing and Plot & Structure. They’re all marked-up and dog-eared! Thanks for all those great ideas!

Great post, Jim. It was perfect timing to hear you deliver these words at the CCWC today. It was just what I needed to hear to help my WIP. Thanks!

C, T&S are really fun to build. In thrillers particularly those are three lifeblood of the story. I like the chart idea, especially if a story has multiple recurring characters that need consistent tension building between them. Since I write military / espionage thrillers Conflict, Tension & Suspense are MAJOR Major pieces of the story. Incredible tension that grows to a suspenseful conflict is what It is all about.

In the military side of the stories those elements can be somewhat simple. Side A wants to kill all of Side B. But when the espionage part of the story kicks in it all gets a little murkier. Because now A still wants B dead but A’s heroic older brother A+ is in love with B’s sister Babe-B and B is willing to exploit their affair to bring A down by his love for his brother A+. Meanwhile A+ discovers Babe-B has a thing for A and goes into a funk and sleeps with the infamous Double-D who is in turn also sleeping with B and passes info to B about A&A+ fighting over Babe-B.

B tries to trick A into giving up the launch codes to Babe-B, but Babe-B realizes too late that she really does love A+ and was only being used by both A and her brother, the despicable B, and Babe-B vows to run away with A+. A+ agrees and they sell fake launch codes to Double-D who doubles the price and sells them to B who tries to launch against A only to find that the codes were not launch codes but lunch codes to get free all you can eat Chinese food at Kenny’s Choo-Choo Chinese Buffet. He arranges to meet A & they face off over bowls of extra spicy Mongolian BBQ Pork and they are both killed by giant killer ninja squids who dispatch them with the tentacle sucker face chinquan-zhi-pho move learned in ancient China’s ninja squid monastary. Meanwhile A+ & Babe-B move to Brazil where they live with relative peace for several years until a surreal culinary accident involving seafood, flan and 150 proof rum ignite an unknown genetic defect that causes them both to swell up & burst into flames in the world’s only known case of explosiphalactic allergic reaction. After those troubled times Double-D gives up ‘the life’ and goes into witness projection becoming a famously sought after Cirque du Soliel dancer known around the world as 3-Breasted Tiffany (aka her stage name…TRIPLE).

now that’s Conflict, Tension & Suspense baby! Yeah!)

I create a Major Character grid and a minor character grid, and as I work with those–and sometimes even “goof” with those–I find conflicts. The tensions, conflicts, and outright wars between characters go into voice journals, where I explore the trouble from the different characters’ POVs. That method has brought my novel more trouble than I know what to do with! But that’s a good thing, right? Right.

Indeed it is! Trouble is your business, so good job!