Today’s post is brought to you by Conflict & Suspense, two things every novel needs. Yes, every, no matter the genre.

I’m not just talking about plot here, but characterization, too. It’s this latter aspect that some writers fail to take full advantage of. To illustrate, let me talk about one of my favorite movies of all time.

12 Angry Menis the 1957 film directed by Sidney Lumet, written by Reginald Rose (based on his play). The plot is disarmingly simple. Twelve jurors deliberate in a capital murder case. The entire drama, save for a short prologue, takes place inside the jury room.

At first, the verdict seems like a done deal. All the early chatter is about how guilty the defendant is (he’s a slum kid, accused of stabbing his father). One of the jurors (Jack Warden) has tickets to the ballgame and would love to get out early. Others don’t see the point in spending a great deal of time actually deliberating.

They take an initial vote. And only one juror, Number 8 (Henry Fonda), votes Not Guilty. Everybody else grumbles.

And for the next hour and a half, we sit in on the deliberations.

The movie violates all the currently fashionable, postmodern, ADHD stylistic conventions. No quick cuts or explosions or overbearing music. It’s all talk. It’s even in black and white, for crying out loud!

Yet, no matter where I happen to come in on the film when it’s on TV, if I start to watch I have to finish.

Why? Because inter-character conflict works its magic. What Rose did was bring together twelve distinct characters, each with their own background, baggage and personality, and throw them into what is essentially a great, big argument.

Therein lies the real untapped secret of creating conflict: orchestration. That means you cast your characters so they have the potential of conflict with every other character.

In 12 Angry Men, for example, there’s a Madison Avenue ad man (Robert Webber) who spouts bromides and tosses out suggestions, just like he would at a brainstorming meeting at the office. “Let’s run it up the flagpole and see if anybody salutes.” He’s amiable, easy with a laugh. But he never makes a final decision. He vacillates. Finally another juror (Lee J. Cobb) gets fed up. “The boy in the gray flannel suit here is bouncing back and forth like a ping pong ball!”

There’s a mousy bank clerk (John Fiedler) who automatically draws satirical comment from the macho salesman (Warden). There’s a coldly rational stockbroker (E. G. Marshall) who arrogantly dismisses all reasonable doubt, until backed into a corner by Fonda. There’s a young man who grew up in the slums (Jack Klugman) who, at one point, turns to E. G. Marshall and asks, “Pardon me, don’t you sweat?”

“No, I don’t,” Marshall says. There is nothing more to that exchange, but the line is memorable because of Rose’s superb orchestration, knowing the personalities and quirks of all his characters.

Then there’s the bigot (Ed Begley) who in one unforgettable moment alienates everyoneelse on the jury.

But it is, finally, the main conflict between Cobb and Fonda that is the focus of the drama. Cobb wants to get this kid executed (for reasons that become heartbreakingly clear at the end). Fonda wants to give the kid his due under the Constitution––the requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

And that’s another lesson about conflict: the stakes. They have to be high. In fact, I hold that death must be on the line. Not just physical death, mind you. There is also professional and psychological death. Unless you have one of these overhanging, your story is not going to be as gripping as it should be.

In 12 Angry Men, physical death is on the line for the kid, but more importantly it’s a matter of psychological death for each of the jurors. After all, they could be sending an innocent man to the chair. In addition, each of them has some inner baggage to deal with. Like the old man ignored by his family (Joseph Sweeney), and the newly naturalized citizen trying to make it in America (George Voskovec).

Orchestration for conflict is essential in any genre, including comedy. Especiallycomedy. Think of, say, City Slickers.You have three friends from the city going on a cattle drive out west. They are very different from each other – one is a joker, one is macho, one is just a loser. Then they come in contact with someone who is unlike any of them – Curly, the ramrod. The comedy flows naturally out of the conflict between the different personalities.

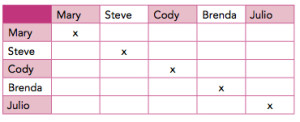

So as you’re getting ready to write, you would do well to create a chart of all your important characters, a grid like the one produced below (taken from my article “Vitamin C For Your Thriller” in the July/August 2013 issue of Writer’s Digest):

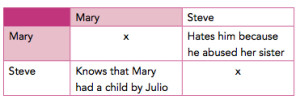

Then figure out points of conflict between the characters, as in this example:

You will be pleased and amazed at all the natural plot tension, subtext and foreshadowing that will emerge from this simple exercise.

Trouble is your business, writer friend. Go make some.

What are some of your favorite ways to increase conflict, tension and suspense in your work?