by Jodie Renner, editor & author

by Jodie Renner, editor & author

Readers of fiction often complain that a book didn’t keep their interest, that the characters, story and/or writing just didn’t grab them. Today’s readers have shorter attention spans and so many more books to choose from. Most of them/us don’t have the time or patience for the lengthy descriptive passages, long, convoluted “literary” sentences, detailed technical explanations, author asides, soap-boxing, or the leisurely pacing of fiction of 100 years ago.

Besides, with TV, movies, and the internet, we don’t need most of the detailed descriptions of locations anymore, unlike early readers who’d perhaps never left their town, and had very few visual images of other locales to draw on. Ditto with detailed technical explanations – if readers want to know more, they can just Google the topic.

While you don’t want your story barreling along at a break-neck speed all the way through – that would be exhausting for the reader – you do want the pace to be generally brisk enough to keep the readers’ interest. As Elmore Leonard said, “I try to leave out the parts that people skip.”

Here are some concrete techniques for accelerating your narrative style at strategic spots to create those tense, fast-paced scenes.

~ Condense setup and backstory.

To increase the pace and overall tension of your story, start by cutting way back on setup and backstory. Instead, open with your protagonist in an intriguing scene with someone important in his life or to the story, with action, dialogue, and tension. Then marble in only the juiciest bits of the character’s background in tantalizing hints as you go along, rather than interrupting the story for paragraphs or pages to fill us in on the character’s life — which effectively eliminates a lot of great opportunities to incite reader curiosity and add intrigue with little hints and enticing innuendos.

~ Include hints at questions, secrets, worries, fears, indecision, or inner turmoil to every scene.

This will keep readers curious and worried, so emotionally engaged and compelled to keep turning the pages.

~ In general, develop a more direct, lean writing style.

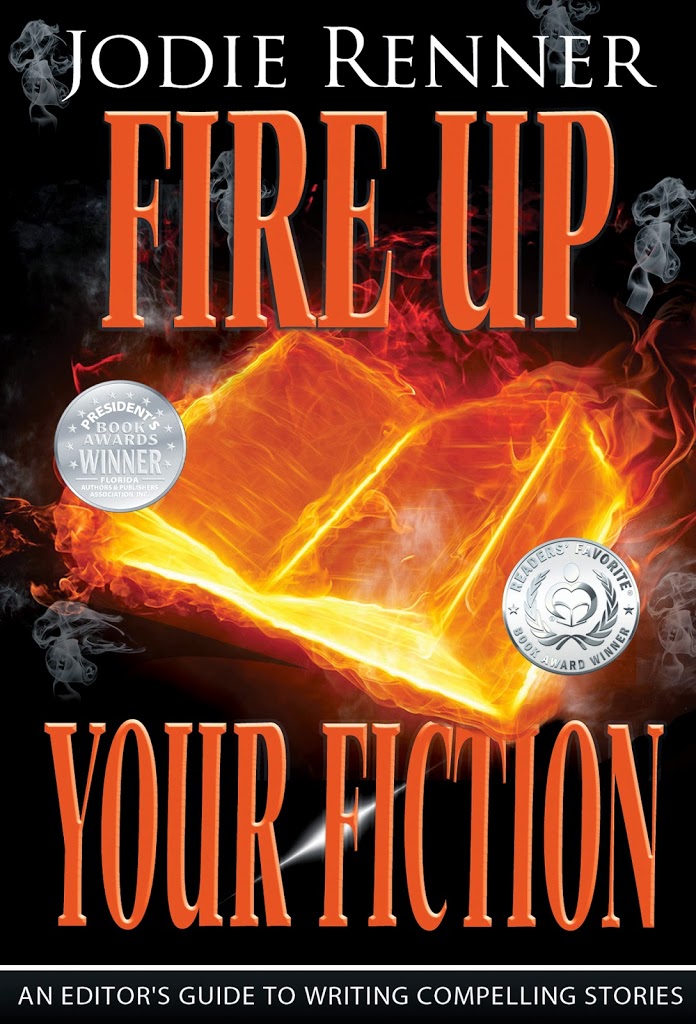

Be ruthless with the delete button so your message and the impact of your story won’t get lost in all the clutter of superfluous words and repetitive sentences. I cover lots of specific techniques with examples for cutting down on wordiness in my book, Fire up Your Fiction.

Be ruthless with the delete button so your message and the impact of your story won’t get lost in all the clutter of superfluous words and repetitive sentences. I cover lots of specific techniques with examples for cutting down on wordiness in my book, Fire up Your Fiction.

~ Rewrite, condense, or delete chapters and scenes that drag.

Do you have slow-moving “filler” scenes, with little or no tension or change? Reduce any essentials from the scene to a paragraph or two, or even just a few sentences, and include it in another scene.

~ Keep chapters and scenes short.

This will help sustain the readers’ interest and keep them turning the pages. James Patterson is a master at short chapters, and his followers seem to really like that. Especially effective for reluctant or busy readers.

~ Start each scene or chapter as late as possible, and end it as early as possible.

Don’t open your chapters with a lengthy lead-up. Every scene and chapter should start with some kind of question, conflict, or intrigue, to arouse the curiosity of the reader and make them compelled to keep reading. And don’t tie up the events in a nice, neat little bow at the end – that will just encourage the reader to close the book rather than to keep reading in anticipation. Instead, end in uncertainty or a new challenge.

~ Limit explaining – Show, don’t tell.

Keep descriptive passages, expository passages, and ruminations, reflections and analyses to a minimum. Critical scenes need to be “shown” in real time, to make them more immediate and compelling, rather than “telling” about them after the fact. Use lots of action, dialogue, reactions, and thoughts. And keep the narration firmly in the viewpoint character’s voice – it’s really his/her thoughts, observations, and reactions to what’s going on.

~ Use summary to get past the boring bits, or skip ahead for effect.

Summarize in a sentence or two a passage of time where nothing much happens, to transition quickly from one critical scene to the next: “Three days later, he was no further ahead.” Skip past all the humdrum details and transition info, like getting from one place to another, and jump straight to the next action scene.

~ Make sure every scene has enough conflict.

In fact, every page should have some tension, even if it’s questioning, mild disagreement, doubts, or resentments simmering under the surface. Remember that conflict and tension are what drive fiction forward and keep readers turning the pages.

~ Every scene needs a change of some kind.

No scene should be static. Throw a wrench in the works, make something unexpected happen. Add new characters, new information, new challenges, new dangers. And the events of the scenes should be changing your protagonist in some way. Change produces questions, anticipation, or anxiety — just what you need to keep reader interest.

~ Use cliff-hangers.

For fast pacing and more tension and intrigue, end most scenes and chapters with unresolved issues, with some kind of twist, revelation, story question, intrigue, challenge, setback or threat. Prolonging the outcome, putting the resolution off to another chapter piques the readers’ curiosity and makes them worry, which keeps them turning the pages.

~ Employ scene cuts or jump cuts.

~ Employ scene cuts or jump cuts.

Create a series of short, unresolved incidents that occur in rapid succession. Stop at a critical moment and jump to a different scene, often at a different time and place, with different characters – perhaps picking up from a scene you cut short earlier. Switch chapters or scenes quickly back and forth between your protagonist and antagonist(s), or from one dicey, uncertain situation to another. And of course, don’t resolve the conflict/problem before you switch to the next one.

~ Use shorter paragraphs and more white space.

Short paragraphs and frequent paragraphing create more white space. The eye moves down the page faster, so the mind does, too. This also increases the tension, which is always a good thing in fiction.

~ Use rapid-fire dialogue, with conflict, confrontations, power struggles, suspicion.

For tense scenes, use short questions, abrupt, oblique or evasive answers, incomplete sentences, one or two-word questions and responses, and little or no description, deliberation or reflection.

~ Use powerful sentences with concrete, sensory words that evoke emotional responses.

Utilize the strongest, most concrete word you can find for the situation. Avoid vague, wishy-washy or abstract words, and unfamiliar terms the reader may have to look up. Concentrate on evocative, to-the-point verbs and nouns, and cut way back on adjectives, adverbs and prepositions.

Also, take out all unnecessary, repetitive words and those wishy-washy, humdrum “filler” words and phrases. And use plenty of sensory details, emotional and physical reactions, and attitude. (For more on this, see Fire up Your Fiction.)

A well-disguised example from my editing:

Before:

Kristen fired him a dirty look, probably because he was doing this in piecemeal and not getting straight to the point as she would have liked him to. Her voice was terse. “Why not?”

After:

Kristen fired him a dirty look as if to say, Cut to the chase. Her voice was terse. “Why not?”

Or just:

Kristen fired him a dirty look. “Why not?”

~ Vary the sentence structure, and shorten sentences for effect at tense moments.

Shorter sentences give a pause, which catches the attention of the reader. At a critical moment, don’t run a bunch of significant ideas together in one long sentence, as they each will be diminished a bit, lost in among all the other ideas presented. You can also go to a new line for the same effect.

For a fast-paced, scary scene, use short, clipped sentences, as opposed to long, meandering, leisurely ones. Sentence fragments are very effective for increasing the tension and pace. Like this. It really works. Especially in dialogue.

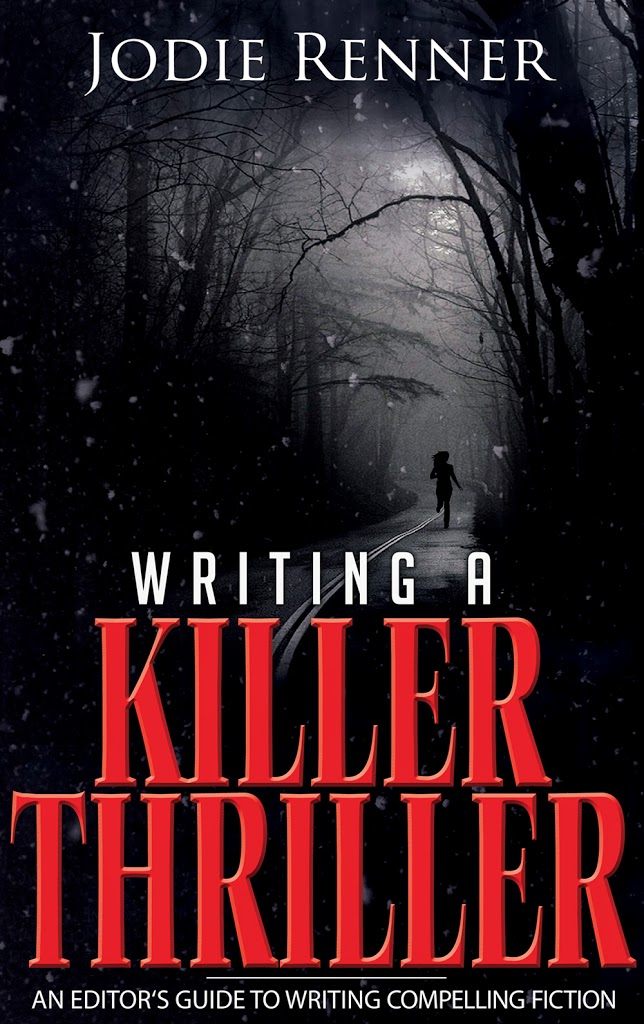

For more tips with examples for picking up the pace, check out Jodie’s editor’s guides to writing compelling fiction, Writing a Killer Thriller, Fire up Your Fiction, and Captivate Your Readers.

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: FIRE UP YOUR FICTION, CAPTIVATE YOUR READERS, and WRITING A KILLER THRILLER, as well as two clickable time-saving e-resources, QUICK CLICKS: Spelling List and QUICK CLICKS: Word Usage. She has also organized two anthologies for charity: VOICES FROM THE VALLEYS – Stories and Poems about Life in BC’s Interior, and CHILDHOOD REGAINED – Stories of Hope for Asian Child Workers. Jodie lives in Kelowna, BC, Canada. Website: www.JodieRenner.com; blog: http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/; Facebook. Amazon Author Page.