by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

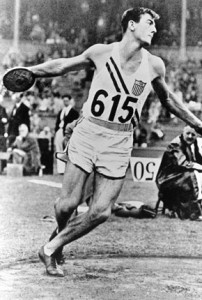

One of the greatest athletes America ever produced was Bob Mathias. Listen to this: in 1948 Mathias was a high school student in Tulare, California. His track coach mentioned he ought to consider the decathlon. This is, of course, ten events, several of which Mathias had never attempted. They trained for three weeks. Three. Mathias won the local AAU decathlon. A short time later, he won the nationals and Olympic trials.

Mathias went to the London games and won the gold medal. He was seventeen-years-old, the youngest person ever to win a gold in track and field.

In 1952 he went to the Olympics in Helsinki, and did what no one had ever done before—he won the decathlon again. To top it all off, he starred as himself in the movie The Bob Mathias Story, which I watched several times as a kid.

I thought of Mathias a few days ago when I read this phrase once again: “A writing career is not a sprint, it’s a marathon.” It suddenly occurred to me that this is inadequate. Why? Because it doesn’t matter if you run 26 miles if it’s in the wrong direction!

Instead, I think a successful writing career is more like a decathlon. There are at least ten “events” you must master in order to compete and win a medal. Here they are:

- Dedication

Are you willing to put in the work? Pay the price? Stick with it and not give up? Will you stay with this even though it’s going to take you years to get there?

Olympic champions start young and spend countless hours practicing, for years, for that one shot at gold. Similarly, it takes a long time and a lot of work to gain a writing foothold these days.

While there are no hard rules on this, suppose I told you that it’s going to take you five years and five quality books to start making solid income as a writer? Will you still go for it?

I hope so.

- Production

Decathletes have to spend a set amount of time every week in training. A writer has to spend a set amount of time every week writing.

You don’t produce books by not writing them. (Maybe I should go into the Zen koan business. Or not.)

Seriously, when I hear people say, “I just can’t write to a quota. I have to get into the mood,” I hear the sound of a cash register not ringing. (See? Zen master!)

- Quality

In sports, practice does not make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect. The precision of your drills is what makes the difference when it comes time for actual competition.

So the words you produce must be quality words. By quality I mean this: the best you can do while keeping your audience in mind.

Who is your audience? Readers. If you’re writing in a genre, you know those readers have certain expectations. You must serve those expectations at the same time you are exceeding them. How? By being an original, surprising them, elevating your book beyond the merely competent.

How do you get to that point? See #4.

- Study

A decathlete watches film of great athletes competing in certain events. Slow motion of champion pole vaulters, shot putters, discus and javelin throwers. You hone your skills partly by studying what others do well.

I can’t understand writers wanting to get ahead in the fiction game not making study of the craft a regular habit. I simply do not get it. Do you want some fresh-out-of-med-school doctor who doesn’t read the medical journals or observe experienced surgeons taking out your spleen?

At least when a writer makes mistakes nobody dies. But the interest of a reader does. And that can mean death to a career.

- Creativity

Did you know that every decathlete before 1968 used either the scissor kick or Western roll for the high jump? That’s because those two techniques were the only ones the dedicated high jumpers ever employed.

Then along came a guy named Dick Fosbury who, in high school, wasn’t able to win in the

high jump using old-school technique. Over the course of time he experimented with methods until he started going over the bar backwards, something no one had ever contemplated before. He began to set records with “The Fosbury Flop” and he won the gold medal at the ’68 Olympics in Mexico City.

All high jumpers and decathletes now use the Flop.

Writer, you need to nurture your creativity, try new things, play and explore. You still need to jump over the bar. How you do that is your individual style.

- Goals

Great athletes give themselves benchmarks to shoot for, and put in place plans to reach them. These goals are measurable. In other words, they can be assessed according to what was done or not done, what was accomplished or not accomplished. Then there is a time for reassessment and recommitment.

Writers need to set goals, too. Not just word count, but the development of future projects, craft study objectives, social media presence, even personal health (which affects production). Goal setting is one of the essential skills of success.

I prepared a short monograph on this topic that can be found HERE.

- Perseverance

Every champion athlete has had setbacks, losses, injuries. There are many, many times when quitting seems like an option. Those are the very times the great ones push on. Like Rocky Bleier, the Pittsburgh Steelers running back who came home from service in Vietnam with a right leg shredded by shrapnel. Coaches and doctors told him to give up football. He refused, and worked harder than everyone else. For two long years he struggled, and made the team again. Two years after that he was a starter. Two years after that he gained 1,000 yards for the season.

The writing life has plenty of frustration and disappointment. A rejection can feel like a shredding of your soul. That’s when you let it hurt for half an hour. Pound a pillow. Eat some ice cream. Cry if you must. But then take a deep breath and go to your keyboard and write something. Anything. You cannot be defeated if you keep pounding the keys.

- Courage

In addition to perseverance, champions have times during an event where they must reach down deep and tap a reservoir of courage. That’s certainly true in the decathlon, the most demanding two days in all of sports. When Rafer Johnson competed for the United States in the Rome Olympics in 1960, he was coming off the effects of an auto accident the year before. His big rival (and UCLA teammate) was C. K. Yang, competing for Taiwan. It all came down to the final event, the grueling 1,500 meter run. Johnson needed to stay within ten seconds of Yang in order to win. But Yang was almost twenty seconds better at this event than Johnson. Johnson reached inside and willed himself to dog Yang’s heels. He finished only 1.2 seconds behind Yang, and took home the gold.

There are times in your writing when you have to dig deep, keep going, try harder. It may just mean hanging on for one last lap. The great thing is, even if things don’t turn out quite the way you want, you will be a stronger writer because of it. No effort is wasted.

- Balance

Athletes have to give their bodies time to recover from an intense workout. There is a delicate balance between exertion and rest. And when it’s a young athlete, they have to figure in school work and a bit of a social life. The number of athletes who were driven too hard by an overzealous parent, and ended up out of athletics altogether, are legion. See, for example, Todd Marinovich.

There is a time to rest as a writer. Personally, I write six days a week. I take Sundays off. It’s hard. I’m like a horse that wants and expects to run on the track. But the day off gives my mind time to rest and recharge. I come to Monday raring to go.

And don’t forget the people in your life. Give them the time they deserve, even though you may have to explain that far off look you get sometimes. You know, the one where you’re thinking what a great scene this would make, or how that bartender over there would be a terrific minor character…

- Joy

A champion athlete has to take joy in his event. Eric Liddell, the Scottish sprinter who won a gold medal in the 440 at the1924 games, was depicted in the movie Chariots of Fire. As the son of a missionary, he was expected to go to the mission field, leaving athletics behind. After his sister reprimands him, Liddel replies, “I believe God made me for a purpose, but He also made me fast. And when I run, I feel His pleasure.”

“In the great story-tellers, there is a sort of self-enjoyment in the exercise of the sense of narrative; and this, by sheer contagion, communicates enjoyment to the reader. Perhaps it may be called (by analogy with the familiar phrase, “the joy of living”) the joy of telling tales. The joy of telling tales which shines through Treasure Island is perhaps the main reason for the continued popularity of the story. The author is having such a good time in telling his tale that he gives us necessarily a good time in reading it.” – Clayton Meeker Hamilton, A Manual of the Art of Fiction (1919)

Just as the decathlon is the toughest of athletic contests, so the writing life is one of the toughest ways to make a buck. Yet isn’t that what makes it worthwhile? When you score a win, and you will––you’ll finish that novel, you’ll start to see some sales, you’ll get an email from a delighted reader––you’ll feel that joy of accomplishment that the ne’er do wells never do.

The easy road is for chumps.

Keep writing.