By Clare Langley-Hawthorne

Coming up on our Kill Zone Guest Sundays, watch for blogs from Sandra Brown, Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Thomas B. Sawyer, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, Oline Cogdill and more.

By Clare Langley-Hawthorne

Today we welcome our guest James Scott Bell to TKZ. Jim is the author of the Ty Buchanan thriller series – Try Dying, Try Darkness and Try Fear (July 09). His latest standalone, Deceived, was called a "heart-whamming read" by Publishers Weekly. He has taught novel writing at Pepperdine University in Malibu, and at numerous writers conferences. In July he’ll be conducting a workshop on suspense dialogue for the International Thriller Writers CraftFest portion of ThrillerFest in New York. Jim is also the author of two bestselling books in the Write Great Fiction series from Writers Digest Books: Plot & Structure and Revision & Self-Editing. A former trial lawyer, Jim lives and writes in L.A. His website is www.jamesscottbell.com

Perhaps you saw the challenge a group of British thriller writers laid down last month. In The Guardian (UK) , Jeffery Archer, Martin Baker, Matt Lynn and Alan Clements declared they are out to end "the reign of the production-line American thriller writers, such as James Patterson, John Grisham and Dan Brown" and return British thrillers to their "rightful prominence."

Perhaps you saw the challenge a group of British thriller writers laid down last month. In The Guardian (UK) , Jeffery Archer, Martin Baker, Matt Lynn and Alan Clements declared they are out to end "the reign of the production-line American thriller writers, such as James Patterson, John Grisham and Dan Brown" and return British thrillers to their "rightful prominence."

Talking a little English smack, Archer said, "The tradition of thriller writing should never be allowed to die. Not least because we are better at it than anyone else in the world."

My thought upon reading that was, We whipped ’em in 1781, and we can do it again.

But I set my musket aside and continued reading. Here’s a clip:

Lynn, author of the military thriller Death Force, said that authors such as James Patterson – who writes, with the aid of a team of co-authors, up to eight books a year – have "drained a lot of the life out of the market". "Look at Fleming, look at Len Deighton – they had a quirkiness to them. Yes they were very popular, and had elements of the formulaic, but there was an edge of originality to them," he said. "All the writers in this group believe in bringing that back … Too many of the American thrillers are just being churned out to a rigid formula. Good writing is never a production line."

"We’re trying to say ‘why would you want to read fairly cynical, ghost-written books which are being pumped out by publishers when there are a lot of good new British writers you could be reading?’" explained Lynn. "We feel the genre has been quite neglected in the last seven to eight years … There haven’t been any new writers coming through. It might be because there aren’t any very good writers, or maybe it’s because publishers and booksellers have been neglecting it – they’ve become obsessed with the big names, and because they’ve got a new James Patterson or John Grisham four to five times a year to put at the front of the bookshop, it crowds out all the new British authors who are coming through."

These writers, who call themselves The Curzon Group, have come up with "five principles" for writing a thriller. They believe–

1. That the first duty of any book is to entertain.

2. That a book should reflect the world around it.

3. That thrilling, popular fiction doesn’t follow formulas.

4. That every story should be an adventure for both the writer and the reader.

5. That stylish, witty, and insightful writing can be combined with edge-of-the seat excitement.

Let’s take a closer look.

1. That the first duty of any book is to entertain.

Check. Without that, nothing else matters, because no one is reading you. And note that entertainment does not mean fluff. Being "caught up in the story" can happen in many ways and in myriad genres.

Our top thriller writers clearly entertain. Look at what’s being read on any given plane on any given day. For a read that gets you caught up in the fictive dream, we Americans are certainly holding our own, wouldn’t you say?

2. That a book should reflect the world around it.

I’m not sure what this means. Social comment? Message? Verisimilitude? You can take it a number of ways.

I’m not sure what this means. Social comment? Message? Verisimilitude? You can take it a number of ways.

I do think a thriller has to "reflect" the world to the extent it establishes the feeling of reality, that the events in the story could happen. How well you do this is a matter of individual style, and avoiding things that could pull readers out of the story.

But this is SOP for any fiction writer, not just those who do thrillers. I’m not sure this principle moves the debate along.

What do you think it means?

3. That thrilling, popular fiction doesn’t follow formulas.

Here, I disagree a bit. There is a reason we have formulas in this world: they WORK. Try making nitroglycerin out of egg whites or lip balm out of sandpaper. We use formulas every day. We’re lost without them.

What most critics mean by this jab is "formulaic," which is a euphemism for "by the numbers" or otherwise without original content and style.

And we’d agree. Thrillers need formula, but should never be formulaic.

So what’s the formula?

For one thing, somebody has to be in danger of death. (I’ve talked elsewhere about the three types of death—physical, professional and psychological. For most thrillers, physical is on top).

Another ingredient: an opposition force that is stronger than the Lead. If not, the reader won’t care about the stakes.

And the Lead has to be a character we care about deeply. Not perfect, and not necessarily all good (think: Dirty Harry). We just have to care, and there are things you do and don’t do to forge that reader connection.

What keeps a thriller from being by-the-numbers is the freshness you bring to it by way of character, voice, style, and the arrangement of plot elements.

Take A Simple Plan by Scott Smith. A tried and true formula: innocent man finds forbidden treasure, succumbs to greed, disaster results (the death overhanging this novel is psychological death, which the Lead and his wife suffer by the end). That story’s been done over and over. But Smith brought to it compelling characters in complex relationships, and a style that drives you relentlessly from chapter to chapter.

Or the film The Fugitive. Innocent man on run from the law. Formula! But what they did with both Richard Kimble (Harrison Ford) and especially Sam Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones) turned it into a classic thriller. We’ll never forget Sam’s line, "I don’t care!" Or the beat where Kimble, trying to get out of Cook County Hospital without being recognized, puts his own troubles on hold to help a kid in the emergency ward.

When the film was over, and Sam does care, we’ve been taken on an almost perfect thrill ride.

4. That every story should be an adventure for both the writer and the reader.

Check. For the writer of thrillers, that means taking a risk in each book, somehow. Stretching the muscles. For example, I love that Harlan Coben has taken Myron Bolitar international in his latest. I’m sure you have your favorite examples, too (what are they?)

No adventure in the writer, no adventure in the reader.

5. That stylish, witty, and insightful writing can be combined with edge-of-the seat excitement.

Who is going to argue with that?

I’d aver, however, that style cannot overcome a weak story construct. So while I’m at it, let me put in a good word for Patterson, who has been castigated by so many. His concepts are terrific. He knows story at the fundamental level. His books wouldn’t do nearly so well without the solid scaffolding of the basic premise.

I’d aver, however, that style cannot overcome a weak story construct. So while I’m at it, let me put in a good word for Patterson, who has been castigated by so many. His concepts are terrific. He knows story at the fundamental level. His books wouldn’t do nearly so well without the solid scaffolding of the basic premise.

Before I can start outlining or writing, I have to have a logline that excites me, that calls up all sorts of possibilities in my mind. That’s something Patterson, Grisham and Brown also have as the baseline of their books. And so do all successful thriller scribes, as far as I can see.

Our team, the American thriller writers, do pretty well after all. So if the Brits want to have a contest, I say: Bring it.

I’m in.

Any other takers?

And what do you think of the five principles?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Coming up on our Kill Zone Guest Sundays, watch for blogs from Sandra Brown, Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Thomas B. Sawyer, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, Oline Cogdill and more.

By John Ramsey Miller

http://www.johnramseymiller.com

When I was in Miami, 17 years ago, a boy of sixteen was killed by one of two off-duty policemen late one night. Andrew Morello was the sixteen-year-old son of dear friends of mine. That was terrible enough, but what followed was a cover-up by the police for a bad shooting. I didn’t write the story for the Miami Herald because I was too close and emotionally involved at the time. And I was involved because I knew Andrew, and I knew he was a good kid who loved his parents. Andrew was dead for being in the wrong place, doing the wrong thing, at the wrong time. What might have been a tragedy turned into a life destroying event because of several things that happened afterward.

That Saturday morning I was in the shower in my home in Coconut Grove when my wife came into the bathroom and said, “John, Andrew Morello is dead. He was killed by the police.”

I learned that Andrew and three of his friends were stealing speakers from a vehicle, and the alarm went off and two off-duty cops ran out of their house and shot Andrew. He was shot in the heart, and his friends drove the van to his aunt’s house a few blocks away. She called 911. Someone cancelled the ambulance, saying it was not needed. The tape of the cancellation somehow was accidentally erased before a voice pattern could be charted. It was obvious that someone, nobody knows who, didn’t want him to live.

The female cop who shot the gun said Andrew was trying to run her down, but his two friends said he was backing up when the shot was fired. The windshield with the bullet hole in it was “accidentally” shattered by the cops before the Morellos’ independent investigators could test it. The CSI’s own test seemed to prove that the cop was not where she claimed to have been when the bullet hit the windshield and supported the evidence that Andrew was not driving toward the cop, but was turned in his seat so he could see while he was backing up away from the cops as the other boys testified. In the end, the two friends with him went to prison because Andrew died and they were taking a radio or speakers out of a Jeep. This was only really covered by the alternative newspaper, NEW TIMES, and it was covered well. The Herald wrote very little about it. The Morellos tried to have this tried by suing the police, but a judge ruled they couldn’t sue the police and closed the investigation, which was performed by the police department whose cops were involved.

The event put me at odds with Janet Reno, the Attorney General, and she and I had heated arguments about the fact that she would not investigate the police, but accepted their “evidence”, saying that I should bring her evidence of a cover-up. I told her that discovering evidence was her job. My wife can attest to her angry calls and our heated debates over the phone. At the time I knew Janet Reno a little, because I had done portraits of her for a NEW TIMES cover article. She was mad at me at the time for using a picture of her wearing bad glasses, but I doubt that was why she refused to investigate unless I came up with evidence of a cover up.

The Morellos have a large Italian family––a close knit bunch who live to love and love to live. Susie and I were taken into their family after I spent a week at the family’s pawn shop in North Miami Beach doing a piece for the Miami Herald’s Sunday Magazine titled “Pawnography”. Every Thanksgiving we had dinner with Joe and Andrea and their large extended family. Turkey and Lasagna. Andrew’s death all but destroyed that family. Not so much his death, as the unfortunate aftermath of it.

The point of this rehashing is that Andrew’s mother sent me an email saying that she wanted to write Andrew’s story. Not with a book in mind, but to tell the story from a mother’s perspective. She said a lot of her friends and family said she should forget it, that the past should left in the past. I sent her the Faulkner quote about the past. I want her to write that because I want to read it. It won’t matter whether or not it is published, because I think it will help Joe, and the family to heal and put it in their past. At least I hope so. I wrote Andrea that until she puts the past to bed, she can’t truly see her future. I know Andrew would want her to be able to do that. I received the first 13 pages and it was all I could do to read them. My wife cried as she read those pages. Of course it was personal for us and we saw the suffering first hand and love the people involved. Reliving the past can be painful but a healing experience. Losing a child is the worst fate a mother and father can experience, and after 17 years it is no easier for them.

And there were letters to the editor and calls and letters to the Morellos (all anonymous) who said all three boys should have been killed, and one that said that if they had raised Andrew right he would still be alive. How people can do this is simply beyond my ability to understand how people can be so cruel in the face of this heart-breaking event. Yes, Andrew was doing the wrong thing, at the wrong time, but he was a child being influenced by other kids. Andrews father owned a large pawnshop and he had tons of speakers that Andrew could have taken with Joe’s blessings, and that haunts his father. It all haunts his parents and friends, including myself. The Morellos are people of integrity and compassion and they didn’t deserve what happened. I believed that the shooter did nothing but make a huge mistake, and that what happened after was the true crime. I don’t believe the cops set out to murder a child, but that they over reacted in the worst way possible. Those cops, who were married, have to live with what happened––killing a child, and the rest of us have to live with the ramifications of their mistake. What haunts me most is that Andrew would have grown up and become a productive member of society because that was where he was headed, but he never got a chance to become that man.

The future is so uncertain that these days I think about the past more and more and it is clearer than it used to be. I guess my mind has polished the rough spots until it’s all glass smooth. Some things cannot be polished until they become smooth, and this is one of those. It was a horror and a tragedy and it changed all of us who were involved. Now when I write what loss does to good people, I do so from painful experience.

“The Past Isn’t Dead, it isn’t even past.”

While we haven’t signed the papers yet, I recently closed a deal to option the screen rights to Scott Free–my second movie deal in three months after a ten-year dry spell in which I couldn’t give the rights away for anything I wrote.

This is very exciting. But equally exciting is the new strategy I’ve adopted for movie sales: think small and aggressive.

Back in the day, when I sold the movie rights to Nathan’s Run and At All Costs, my agent negotiated big bucks from big studios which bought the screen rights outright, “forever and throughout the universe” (that’s actually the contract language). They made big promises but never made the movies. And I’ll never see the rights again.

With Six Minutes to Freedom and, more recently, Scott Free, I sold options for the screen rights for a limited period of time to independent producers for whom filmmaking is still considered as much an artform as a business. I don’t get paid nearly as much on the front end, but if the film gets made, it’ll be champaign time. If they don’t get made, the rights will revert to me, where in the worst case they will moulder away in my closet instead of someone else’s.

Given the above, what follows may just be rationalization on my part, but it feels legitimate to me:

The future of filmmaking lies in the hands of aggressive new producers who are tired of what studio pictures have become. I believe that the exclusion of studio films in the last Oscar race portends the future of filmmaking. There will always be a huge market for the special effects-laden summer crowd pleasers, but it’s becoming clear that compelling stories lie in the hands of the indies.

We’ve been to this place before. Remember the 1970s? That was the decade when upstarts named Spielberg, Coppola and Lucas turn Tinseltown upside down. The revolution that started in the ’60s with films like Bonnie and Clyde and In the Heat of the Night paved the way for ’70s classics like Jaws, Star Wars and The Godfather. These films set the old Hollywood model on its ear. While studio monoey was involved in all of these films, the creative momentum came from unknowns who shared a hunger for a new breed of storytelling.

But new breeds age. Spielberg and Coppola are brilliant filmmakers, just as John Huston and Alfred Hitchcock were brilliant in their day. Their enormous success brought billions of dollars to the box office and made mega stars out of countless nobodies, including themselves. But that kind of success ultimately leads to excess–not just in terms of expenses, but also in terms of leanness in storytelling. (The difference in directing technique between American Graffiti and the latest Star Wars installment is explained by more than just a limitless budget.) The studio films of today are in their own way every bit as bloated as the pageantry of Cecil B. DeMille and Joseph L. Mankiewicz from the ’50s and ’60s.

Then along comes Slumdog Millionaire. And Doubt, and The Reader. The year before, the Academy nominated Juno and Atonement for Best Picture. Story for story’s sake is mattering again, and in every case, this new revolution is being led by relative newcomers–certainly by lesser knowns.

When I speak to the young, hungry producers who bought the film rights to my books I hear something I haven’t heard from Hollywood types in a long time: Enthusiasm. If, like the others, these movies never happen, I’ll know that the effort will not have failed for lack of that one key ingredient to success.

So, what do y’all think? Discounting for the summer blockbuster spectaculars, is it possible that we’re entering a new era of big screen storytelling where character and plot matter at least as much as the intensity of the explosions?

======

Coming up on our Kill Zone Guest Sundays, watch for blogs from Sandra Brown, Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Thomas B. Sawyer, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, Oline Cogdill, James Scott Bell, and more.

I just handed in the final page proofs for my next thriller, which is always an exhilarating/terrifying moment for me. Exhilarating because I’m finally completely done with the book. And terrifying because from here on out, it’s beyond my control. I have to keep my fingers crossed that the myriad small changes I made are inserted into the final manuscript (since the final few drafts are actual paper copies that get mailed back and forth, sometimes things slip through the cracks. Sad but true, and the best argument I can see for switching to electronic editing across the board).

In line at FedEx, I started thinking about all of the things that are beyond our control as authors (many of which people assume we do control). Here’s my list:

Covers: I always fill out a lengthy form detailing characters, scenes, and plot points. I attach images that I think would look great on the cover, forward jpgs of covers that I loved from other people’s books, and pitch a few concepts. Now, so far I’ve been fortunate enough to receive covers that were vastly superior to anything I could have conceived. But still, there are always a few little things I’d prefer to change. This time, after some back and forth my publisher incorporated a few of the changes I requested into the final design. Here’s the original:

I felt the background color was too drab, and all of the text was at the bottom, so you barely noticed anything above the center of the page.

Now here’s the final version:

Better, right?

Typos: I’m not saying I’m perfect, but occasionally glaring typos appear in the text that were in no draft of the manuscript I submitted. My book club read The Tunnels, and when I walked in for our meeting three people shouted out, “Page 67! What happened there?” Half of the night was consumed by a discussion of some of the typos in the book. Somewhere between my final edits and the typesetting process, new typos appeared. Again, beyond my control (also the reason why I never crack the spine to read the final product. I have never once read one of my books after mailing off the line edits, because if I spot a typo it drives me nuts).

I will say that in book publishing, I still have far more control than I ever did as a magazine writer. Back then, I’d hand in an article and six months later, something came out with my name on it that was virtually unrecognizable.Not always, but frequently enough to be depressing. In book publishing you are definitely allowed a firmer hold on the reins.

Off the top of my head, this is what I came up with (my brain is officially mush after spending the past week muttering sentences aloud over and over again). But I’d love to hear of more circumstances beyond our control, if they occur to you.

By Joe Moore

When you buy a book, do you buy new or used? If your favorite author just released a new hard cover, do you snatch it up immediately or wait for the mass market paperback? And in either case, do you buy a used copy or new?

As writers, how should we look at used book sales? I’m not talking about out-of-print books where about the only way to get a copy is on eBay or an Amazon used book vendor. I’m talking about the book you just had published a month ago. Do you look at used book sales as money lost? After all, neither you nor your publisher earns any revenue from used sales.

As writers, how should we look at used book sales? I’m not talking about out-of-print books where about the only way to get a copy is on eBay or an Amazon used book vendor. I’m talking about the book you just had published a month ago. Do you look at used book sales as money lost? After all, neither you nor your publisher earns any revenue from used sales.

If you were lucky enough to have a book that sells well, but you started seeing hundreds of used copies for sale on Amazon, eBay and other sources, would you be upset knowing those were royalty-less sales?

Here are some random thoughts in no particular order for and against used book sales.

For: If someone buys a used copy of my book and they like it, they might buy a new copy of my next one when it’s first published.

Against: If my sales were approaching the point where the publisher considered a second (or third) print run, I may never get it because the used sales took the place of the additional run.

For: Used book sellers sometimes hand-sell books that eventually help build a writer’s career.

Against: The biggest used book seller in the world is Amazon and there’s no hand selling going on there.

For: All used books were originally purchased as new so there’s the royalty.

Against: For each new book sold, 5-6 people may read it as a used book equating to lost royalties.

For: Used books help perpetuate my "brand" and name recognition. It gets my name out into the market place to readers who can’t afford the price of new books.

Against: Used books provide the same level of enjoyment to the reader as a new copy but with no return for my efforts.

The argument for and against is a polarizing debate. For every point in favor of used sales, there’s an equally opposed view. What is your feelings on this? Do you get hot under the collar when you see your books being sold used or do you rejoice that your name is getting out there to a new reader? Should we look at used book sales like car manufacturers look at used car sales? Are used book customers a segment of the reading population that probably will never start buying new books? Did you feel different about buying used books before you became a published writer?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Coming up on our Kill Zone Guest Sundays, watch for blogs from Sandra Brown, Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Thomas B. Sawyer, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, Oline Cogdill, James Scott Bell, and more.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Coming up on our Kill Zone Guest Sundays, watch for blogs from Sandra Brown, Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, Oline Cogdill, James Scott Bell, and more.

by Clare Langley-Hawthorne

http://www.clarelangleyhawthorne.com/

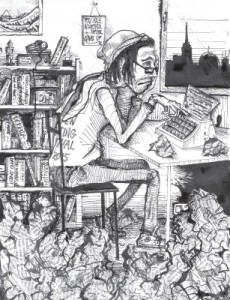

We at TKZ had a mini writing school yesterday for our Sunday post and one of the questions posed was about how to deal with writer’s block. At the moment I’m on the final, final, final edits (that’s when even I am totally sick of the manuscript!) and what I am struggling with is what I call ‘final editor’s block’.

I’m not talking about the big stuff like plot or character – I’m talking about those small, yet irritating things that you start to notice when your on the homeward stretch. For me the things I particularly notice are:

The problem I find is that when in final edit mode I often experience ‘editor’s block’ – when I’ve lost the ability to know what should be changed and what should not, when I’m afraid I’ll start buggering up the good bits and when I’m down to the last persnickety edits and I can’t think of how to improve the manuscript without someone else’s ‘mouth going dry’.

It drives me a wee bit crazy but as much as I read Dickens (far more inspiring than the thesaurus); listen to tortured 80’s music; and brainstorm ideas, I still feel, well, ‘blocked’.

For me writer’s block per se hardly ever happens and when it does I have lots of strategies (mostly driven by panic) that help me overcome the fear of the blank page. It’s another skill entirely, however, for me to overcome the inner ‘editor’s block’ I get when gazing at the page crowded with words – words that I have already combed and preened over many iterations…

So any ideas on how I can tackle the dreaded ‘editor’s block’? How do you manage the homeward stretch edits and, let’s face it, do you ever know when you are really, well and truly ‘done’?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Coming up on our Kill Zone Guest Sundays, watch for blogs from Sandra Brown, Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, Oline Cogdill, James Scott Bell, and more.

Here’s a question from Joy F.

Q. What are some methods of getting over writer’s block?

A. [From Joe] Getting the juices flowing can be tough sometimes. We all experience it. Here are a few tips that might help. Try writing the ending first. Consider changing the gender of your character or the point of view. Tell the story or scene from another character’s POV. Just for grins, switch from third person to first or vice versa.

You don’t have to keep the results of these exercises but they might boost your imagination and get you going again.

By John Ramsey Miller

http://www.johnramseymiller.com

I have a letter I keep in a lock box that my mother wrote to me thirty years ago just after she discovered that her breast cancer had returned in a big way. That letter arrived in the brand new lock box a few days after she died, handed to me by my father. In the letter she tells me how wonderful her life was and no regrets, and how much she loved me, and how everybody needs a lock box for important papers so here’s one I bought for you. That letter is still in that lock box under my bed––a prized possession. I like to read it. My mother’s penmanship was flawless. My own is quite good thanks to public schools in Mississippi and a lot of practicing over the years.

Thirty years ago people still wrote letters, but as long distance calls grew less expensive, it became easier to call and talk than to write a letter. With cell phones we are always near enough to a cell tower to talk whenever we feel like it. With the Internet, people send electronic messages. I get e-mails from friends almost every day, and I almost never print them out. Mostly the communications are short blurbs, and messaging on the cell phone means even briefer information passing. Twitter is dumbing down America faster than evolution. I text with my wife because she is at her desk and she can check every once in a while to see if I’ve said anything worth responding to. She texts me because it doesn’t interrupt my writing time.

Back when we all wrote letters, we put a week’s or a month’s worth of news in the letter. We wrote our feelings and what life was doing to us. You’d sit with a pen imagining the person we were writing to and thinking about that person who’d be reading it. The mail came, you opened a letter, you unfolded it and you read the letter in your hand. The paper had been in the hands of the person who’d written it. You could fold it up and open it again later, as often as you wanted to for as long as the paper held up. Think of the archives filled with personal letters from the famous and not so famous. I think of Ken Burns’ Civil War series for PBS and what it would have been without the personal letters from the time that gave it texture and meaning and humanized the war. We are losing history. The e-mails are being deleted almost as fast as they are read, which probably goes to what they are worth. We don’t compose e-mails the same way we did letters. I officially name it “jit-jotting.”

Recently I sent my step-mother a letter. She is in an assisted living facility in Dallas, and I love her dearly. Her daughter told me that she reads that letter over and over again. That letter connects us in a way no telephone or e-mail on a screen can. After my father passed away my brother went through his papers and he gave me several letters I’d written to him over the years, along with pictures I’d sent in the envelopes. I could tell he’d read them over and over, and I found myself wishing I’d written him more of them.

My dead mother is somehow still alive in that letter. The letter from my mother, only matters to me now––the living half of the communiqué. I suppose after I’m gone my children will dispose of it, and that’s okay with me since nobody else will feel the connection or its importance.

I think of the books written from the collected letters between people, mostly famous, and I wonder how many will be written in the future from the collected e-mails or telephone conversations of famous people. There is a style in written letters that aren’t reflected in most e-mails and lost forever with telephone calls.

Maybe part of the reason we write books is to leave something of ourselves behind. We are all jit-jotting our way through our days and our lives, and are leaving a thinner and thinner trail as we go into the future––and it seems to me to be a bleaker place in most respects.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Coming up on our Kill Zone Guest Sundays, watch for blogs from Sandra Brown, Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, Oline Cogdill, James Scott Bell, Alexandra Sokoloff, and more.