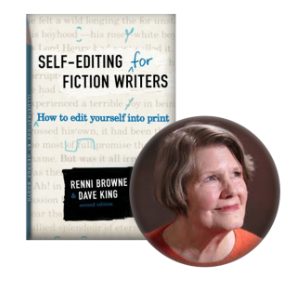

I have a treat for Kill Zoners today. For years, I’ve followed advice from a Tucson, Arizona-based writer resource agency aptly called The Editorial Department. A craft book titled Self-Editing For Fiction Writers – How to Edit Yourself Into Print, co-written by Renni Browne and Dave King, formed a foundation to my writing start. Today, it’s well-worn, dog-eared, and full of red and yellow mark-ups.

Renni Brown founded The Editorial Department in 1980. Now her son, Ross Browne, serves as its President and Director of Author Services, and I contacted him asking for permission to share this treat on The Kill Zone. It follows an Editorial Department newsletter several weeks ago that said this:

After 53 years editing books, teaching writing and editing, and helping hundreds of authors launch successful careers, our founder Renni Browne has made the decision to retire. It’s our pleasure to share some of the guidance, feedback, and encouragement she provided to our authors over the years in her own words. Here is her essay titled The Editor Over Your Shoulder which is a collection of tips.

Why you shouldn’t explain emotions to readers.

Strong feelings usually speak for themselves.

A word about explaining emotions to the reader. Showing them is so much better. People love to pick up on the codes from the signals we all put out—we spend many of our waking hours doing it—and in literature it’s one of your strongest forms of reader participation. So, the less you explain things to your readers, especially characters’ emotions, the more intense their involvement. There will be times when an explanation will be unavoidable or even desirable, but as a general rule, when you catch yourself explaining how a character feels, first see if the reader can’t discern the emotion from what you’ve already written. If you’re sure he or she can’t, try to find a way to make that possible. In the example I quoted, interior monologue would probably be the way to go.

A word about explaining emotions to the reader. Showing them is so much better. People love to pick up on the codes from the signals we all put out—we spend many of our waking hours doing it—and in literature it’s one of your strongest forms of reader participation. So, the less you explain things to your readers, especially characters’ emotions, the more intense their involvement. There will be times when an explanation will be unavoidable or even desirable, but as a general rule, when you catch yourself explaining how a character feels, first see if the reader can’t discern the emotion from what you’ve already written. If you’re sure he or she can’t, try to find a way to make that possible. In the example I quoted, interior monologue would probably be the way to go.

On writing a bookworthy sleuth.

Encouragement for an author with a bland protagonist.

Since the story’s success hangs, in part, on the protagonist, let’s talk about yours. Bailey has a mysterious past (which I’ll talk about more in a second), and she’s got a trauma she’s working to overcome (an arc). She has a solid foundation—as well as a great deal of unrealized potential.

She is a big city girl who moved to the backwoods, and by the time we meet her, she seems pretty well adjusted. Yet this is a missed opportunity for conflict. As a transplant to the Blue Ridge (and the South in general) myself, I remember the transition being a LOT more rocky than Bailey seems to have found it. It’s one thing for her to appreciate the differences, but it’s another to embrace them all so completely and so soon. In other words, we feel like we’ve missed out on some of Bailey’s character development here.

Bailey is also part of a grand tradition of journalist detectives, and as such, she has quite a bit to live up to here. It’s not enough for a protagonist (in any genre) to be good—they need to be unforgettable. What’s unique about Bailey? What makes her stand out? She’s not a wisecracking reporter (a la Fletch), nor is she quirky (like Jim Qwilleran of The Cat Who series). What—in short—is her angle?

On what makes a memoir truly satisfying.

To an author whose omissions weakened the impact of a riveting life story.

As I said, a good memoir reads like fiction, with the author in the role of the protagonist. Not that it should be a series of dramatic scenes with the plot of the author’s life, but the events need to be recounted dramatically, and the author—the hero—is necessarily an invention, a character. This book seems to have been written from your intuitive grasp of this reality about memoir, which is why so much of it is entertaining and why I believe readers will care about you even if they don’t know you personally.

A good memoir also tells the truth about its author. Not the facts, a great many of which may be honorably withheld. In reviewing Kazan in the Times, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. concluded by describing A Life as “the impassioned testament of an artist who has done his valiant best to tell the truth about himself.” You’ve omitted a lot of facts, which is fine. The omission of the truth of much of your feelings (though excitement is conveyed with stunning effectiveness) hurts the memoir.

A truth you’ve withheld about yourself that I think you shouldn’t is your volatile personality, your extremes of temperament. You already come across as passionate, extraordinarily eloquent, full of surprises, given to extremes. It will come as no surprise to the reader to learn that you possessed (until later years, when you mellowed!) a temperament that made you difficult to live with and work for. You needn’t go into self-analysis—you can simply say you tended to get carried away with the urgency of the moment and ranted, sometimes scaring the daylights out of people or infuriating them.

You’re very good at capturing the atmosphere of the era you’re writing about, whether it be the political climate or the way things worked in publishing. But from time to time you dramatize events with so much detail that readers will experience fatigue or burnout trying to keep track of all the names and developments. I’ve given you some guidelines for cutting and tightening. You’re too close to your story to sense where it’s overkill.

What I’ve done in the document that follows is go through the book, pointing out places where I think you’re losing your readers and making suggestions to keep that from happening. I’ve seldom stopped for praise, so let me cover that base here: I’ve loved working on this memoir. Its flaws you can and will fix. It’s an energetic, provocative, surprising, engaging memoir, as full of twists and turns as a good novel.

On what literary agents and publishers want from a first novel.

To an author whose manuscript doesn’t (yet) hit the mark.

Although I thoroughly enjoyed your novel, I’m going to begin by setting you straight about its weaknesses, because so much of what I have to say is in the context of today’s ruthless and often dismal marketplace for debut fiction.

That marketplace does exist. Publishers have to bring out first novels or they’ll never have new writers to make money for them down the line, and most publishing editors I know are actually on the lookout for the new novelist who’s going to break out.

By which they mean: fiction that’s strongly plotted, that has a story they’re confident readers will be caught up in, a story that won’t let them go, a story that will resonate with its readers after (to their sorrow) they’ve reached the final page. This means the novel has a strong, fresh, original plot–yet what actually creates that level of reader involvement is characters that are irresistible. Not just appealing, not just captivating, but so captivating that the reader cares intensely about at least one and hopefully all of the main characters and has a serious stake in what happens to them.

And as if that weren’t enough, the editors want the novel to be superbly (preferably brilliantly) written, in prose with a distinctive narrative voice that holds up all the way through. When they think they’ve found such a novel, it gets one of the pitifully few spaces for first fiction on their list.

On the problem with cartoonish action hero battle scenes.

And why believability matters in action thrillers.

Your battles are vividly described with details that put the reader on the scene. But these are cartoon battles, never credible because the level of violence dealt to Cramer is often greater than any human could survive. A middle-aged man who gets thrown with enormous force into wall after wall, or slammed against a marble floor littered with glass shards, doesn’t pop up merely cut and bruised to fight yet another foe who’s possessed of superhuman strength. A young woman whose arm has just been virtually wrenched out of its socket doesn’t get hurled from the top of a gallery “into the abyss” and manage to grab a rung and hang on. Passages like this one occur frequently:

He picked me up and slammed my back down against the roof, harder. I recoiled from the pain. My hand was throbbing. My back was screaming.

His back is screaming? This is the ninth or tenth time Cramer’s back has been slammed against concrete or a wall or a roof. His back should have been broken long before now.

The problem with cartoon battles, however much fun they may be to read, is that they keep readers from accepting and fully entering the world you’ve created. You really want them to do this so they’ll care on a deep level about what happens in that world—not just have a good time reading about it. This means you need to stick to the writer’s obligation to tell the truth. Telling the truth for a writer involves making things real for the reader. That means not violating (at least, not strenuously violating) the physical laws of nature if you’ve set your story up so that you’ve got aliens fighting humans who have a home-team advantage.

On the importance of dazzling dialogue.

And a tip on how to write it.

You probably have a pretty good idea of what mastering dialogue could do for your writing. If you write short stories or novels, you want your characters to captivate and convince the reader. Those characters come to life—or fail to—when they speak.

Crisp, revealing dialogue that fits naturally into the mouth of its speaker is something most serious writers work hard to achieve.

You may not know that many literary agents and acquisitions editors skip to the first dialogue passage when they’re “sniffing” manuscripts to determine what’s going to make it into the briefcase for reading. But understanding the importance of superb dialogue doesn’t automatically translate into writing it superbly.

The reality is that nothing translates automatically into the creation of superb dialogue—not even, necessarily, that brilliant, tone-perfect “ear for dialogue” few writers are blessed with. Writing superb dialogue starts with superb characterization—it takes complex, distinctive, interesting people to have interesting things to say to each other, to speak with snap and bite and occasional wit. Such characters can only be created by a writer of some intelligence and imagination. So it follows that if you have strong characters, the chances are that you can create strong dialogue for them. If you know what its components are, you can take steps to make sure your dialogue hits the mark.

On the importance of convincing motivation for a character’s choices.

To an author whose well imagined character does implausible things to serve story.

The first thing I want to say, because I’m going to come down hard on you in one area, is that you are a superb writer with a strong plot and a really interesting heroine.

So what’s the problem?

Motive. Why on earth does Alice, as you’ve characterized her, hang out with Preston? Get into his car? Let him go on doing the repulsive sexual things he does until the inevitable rape? After a while we learn that she loves being treated like a grownup, but by Preston? Loves that enough to put up with what goes with it? It’s just too hard to believe.

There’s no evidence in these pages that she likes him, enjoys him, thinks there’s anything good about him. As for his romantic and sexual moves, not only do they disgust her, but he’s her sister’s husband! It’s hard enough believing her sister would marry this older jerk with the ghastly manners, bizarre behavior, and receding hairline, but we can assume she’s dumb. Alice we know, and her letting Preston get by with murder with her before he literally murders her sister just doesn’t make a lick of sense.

There are two things I can think of that will keep this from making the story unbelievable. First, you have to give Preston some appeal. Make him fun, make him endearing in some way, give him a good side. Right now he’s a cartoon villain, and no child of any age with a lick of sense would go anywhere with him after the first time. And if he forced her to, she’d tell somebody. Or if she didn’t, she’d act so traumatized that somebody would notice and question her until she spilled or they got suspicious. But this issue is entirely solved if he’s got some good points to balance the awful ones.

Second, you need to have Alice get something out of their encounters that’s important to her. It’s not enough just to let us know that he treats her like a grown-up–show him doing that, show her reveling in it, have him be sweet about it. Let us know from the get-go how bad things are at home, which will set up her need for the “love” he showers on her.

Of course, you show us her mounting awareness that what he’s doing–what they’re doing–is wrong. Really wrong. The older she gets the more she realizes how wrong it is, the more she tries to extricate herself from the relationship the more threatening he becomes, and so on.

If she’s going to survive this ghastly childhood, you might consider having Preston leave her alone for periods. Or having him be away for some reason for a while. Or simply having him not be “at” her all that often.

Alice is a wonderfully developed character who’ll be totally convincing–if you can just make the reader understand why she lets Jack do what she does.

On scene versus narrative summary.

Encouragement to an author who leans too heavily on the latter.

Your novel has a lot going for it: a wonderfully rendered rich tapestry of a setting most readers will find fascinating, a dysfunctional but loving family with conflicting aspirations at the center of which is a young man who keeps sacrificing his happiness to fulfill what he sees as his family responsibilities.

You have a marvelous eye for detail and sense of place. These gifts enable you to recreate India so vividly that your readers will live there for the length of the novel, immersed in the scene except for a brief side trip to Russia. You also recreate Indian culture beautifully, its standards, mores, limitations.

We come to know the family well enough that we feel we’re a part of it, following its members over a period of nearly twenty years. There’s a sense of authenticity in your depiction of family life that makes its members and what happens in their daily life real to the reader.

But for all these virtues, there are ways you’ve handled your story and the characters who enact it that make it hard for readers to be as involved as you want them to be. Or, to put it another way, you tell the story in a way that at times makes it too easy for the reader to drop out of the novel.

All stories need narrative summary—a novel consisting of nonstop scenes would lack texture, offer no setting, and be exhausting to read. But you seriously overuse summary in this manuscript. Narrative summary fills the reader in, tells rather than shows. Scenes involve your readers, putting them in the story, making them part of events as they’re happening. Readers don’t want information, they crave experiences. They need dialogue—they need to hear your characters talk. In proportion to the length of the novel, there’s very little dialogue. And very few scenes—again, considering the length of the novel.

And it’s in scenes rather than narrative summary that conflict is made real for the reader–and conflict is something this story needs a great deal more of, because it’s what drives fiction, what keeps readers reading. When conflict does arise, you seldom give us an all-stops-out immediate scene. More often there’s a scrap of a scene, or the conflict takes place offstage. (For example, we never see Ishab beating Kash, and when they fight verbally, we only hear scraps of the conversation.)

On pace of character development.

A quick reflection on the value of avoiding too much too soon.

The process of creating interesting and memorable characters whose fate readers can develop a stake in is just that: a process, not an event. You want readers to get to know your characters the way they get to know people in real life—a little at a time. So in the first five pages, writers should usually be more concerned with introducing their character(s) in a compelling fashion than developing them to any significant extent.

On overwriting.

To a skilled author guilty of this cardinal sin.

So you’re a talented writer. Excellent!. You’re also an overwriter. Not good! You overwrite because you don’t realize how effective something you’ve just written is–and so you add to it, puff it up, emphasize it, repeat it in different words, draw it out, etc.

Overwriting undermines the effectiveness of what could otherwise be a really captivating story. It signals the reader that you’re trying too hard. It makes you look amateurish—which is a shame, because you aren’t amateurish, you’re a good writer with amateurish habits common to many first novelists. Fortunately, these habits are easy to get rid of once you recognize them.

On narrative summary.

To an author overusing a useful literary device.

Part of the problem is your approach to the story, which is heavily weighted in favor of narrative summary. Very often you summarize character attributes, scenes, dialogue, events, all sorts of developments. Narrative summary has its place and makes a fine showcase for that wonderful voice of yours, but readers need to hear characters speak, see events happening, participate in scenes—and you short-change them in this respect. Very often, instead of scenes, we get information.

It’s a natural but misguided impulse to let your readers know as much as possible about your novel’s setting and main characters as soon as you can. The result is often an opening, or even a whole novel, whose sheer bulk of information muffles the drama and emotion and slows the pace. But readers are like children—they want the good stuff, they want it now, and they don’t care what you think is best for them. The good stuff is story—dramatic character interaction and intriguing situations. Fiction doesn’t run on information; its fuel is the opposite, an information vacuum you might think of as mystery. Readers keep reading to find out what happened, why, and what will happen next. The more information you give them, the weaker that vacuum becomes. This novel is overloaded with information, especially but not exclusively at the beginning.

On making a well imagined villain more believable and frightening.

Breaking from stereotypes may be the answer.

The situation in the opening scene of this terrorist thriller could hardly be more tense, but the execution could have a much sharper impact. Your terrorist, however convincing his credentials, might as well hang a sign around his neck saying: I’m a fanatical terrorist! I belong to Al Qaeda!

He fits the stereotype perfectly, and his behavior is provocative. But what if he were polite instead of rude? Soft-spoken? What if the captain and co-pilot were still uncomfortable but had nothing concrete to base their discomfort on? He’d be a lot scarier. You see, stereotypical villains aren’t real enough to scare us. But suppose Malik is the living, breathing ball of rage you depict him to be, seething with hatred for Americans, and he’s trying to conceal it? So he keeps his voice low, his words polite, but he’s still seething with hatred.

Now you have something really interesting, a terrorist who’s trying to hide not just his identity and agenda but his essence, and he can’t. He says something perfectly nice and it sounds menacing. Think about it. Even pre-9/11, these guys would not have wanted to alarm anybody or call attention to themselves. So Atta would be polite. (On page 95 he engages in “pleasant conversation” with an older couple; on page 96 he smiles at security guards.) But nobody filled with as much hatred as he turns out to be would be able to pull it off.

On faith in a coming-of-age novel.

To an author struggling to make her character’s faith a driving force of a compelling plot.

The motor for this novel is Gina’s desire for God, yearning for intimacy with God, and longing for a sign. Yet this wonderfully forthright, up-front, articulate character who in her first breath as a character is praying doesn’t seem to have any clear notion of what kind of sign from God she wants, or what that means to her. Nor do we know why she wants it in the first place. We learn almost immediately that her parents aren’t really religious—that is, they go to a church but have no discernible spirituality. Gina, on the other hand, is actually a budding mystic, though she wouldn’t have the first notion of what one is.

She’s been growing up in a town where the range in religion flavors goes all the way from A to, maybe, G. You’ve got your Baptists and your Pentecostals, your Methodists and suchlike, then there’s the fringe snake-handling congregation, but her town doesn’t have an Episcopal church, no outside influences that might have inspired in Gina a desire for intimacy with God. Yet this is what she wants–more than anything on earth. Even more than red shoes and red sequins and to wear Fire ‘n Ice lipstick and get kissed on the lips thus rendered appropriately seductive!

And this isn’t just a passing phase with her, either. She keeps praying—entertainingly and intensely–through the whole novel. Nor does any experience that befalls her seem capable of entirely snuffing out this desire for God, though it’s stronger at some points than at others. It’s a flaw at the core of the story that the desire isn’t always credible. Part of the problem is its etiology, but part of the problem is that the desire isn’t made real enough throughout. You’ve presented us with a character who is supposed to be in love with God? Then it’s up to you, her creator, to make us absolutely believe she is.

Now, unless you want to afflict her with an unhealthy obsession (which I know from our conversations isn’t your intention at all), this can’t ever seem to be a one-way love interest. You make it two-way in Sewanee (and with an occasional fleeting hint—a crumb, really) but basically, you have Gina waiting for a dad-blamed sign—which she indeed wouldn’t be able to define but shouldn’t be 100% vague—and getting mighty little from the Lover she longs for. NOT FAIR. Not like God, not a’tall. More importantly, not credible. It’s undermining the hell out of your motor.

Even more important, it keeps the single most important element in your novel from seeming 100% authentic, or from holding up 100% of the way. It has to hold up 100% of the way if this book is to fulfill its wonderfully rich potential. It has to be made totally real and will, as a result, become absolutely, wonderfully comic. (Not unlike God himself in one of his lesser-known attributes) And the only way you can accomplish this, since you’re God in Gina’s universe, is to go into the deepest part of yourself, from which Gina came, and let her experience some courtship. A passionate longing for God is weird, to say the least. It’s not what teenage girls want but it’s what this one wants. Again, your most important task is to make us believe it, make it real the whole way. Make it the most authentic element in this book, not sometimes authentic and sometimes grafted-on.

On engaging readers’ imaginations.

And the value of never explaining emotions.

People love to pick up on the codes from the signals we all put out, and in fiction it’s one of your strongest forms of reader participation. So the less you explain things to your readers, especially characters’ emotions, the more intense their involvement. There will be times when an explanation will be unavoidable or even desirable, but as a general rule, when you catch yourself explaining how a character feels, first see if the emotion can’t be discerned from what you’ve already written. If it can’t, try to find a way to make that possible.

Phrases like “I was terrified,” “He made me so nervous I could hardly speak,” and “My heart was beating so fast I was afraid she’d hear it,” show up with dismaying regularity in the fiction of novice writers.

On dialogue.

Quick tips for new authors.

- Never, ever explain your dialogue. If it doesn’t convey what you want, rewrite it.

- Paragraph whenever a character starts speaking unless just a very few words precede the dialogue (He looked up.) Don’t bury your excellent dialogue—set it off. Paragraphing for dialogue also makes a dialogue scene look more inviting, thanks to the white space on the page.

- Use plenty of sentence fragments. Most people do in conversation, so have your characters do it more often.

- Use past perfect tense rarely—and only when it’s really necessary.

- Screenwriter’s trick: Try to avoid direct answers to questions asking for a yes or no. The answer is nearly always obvious from the rest of the sentence.

On character autonomy.

Why you best characters need to think for themselves–and sometime surprise you.

Every serious fiction writer tries to create rounded, fully dimensional characters who take up space when they enter a room—characters the reader will care about. Most fiction writers call on memories of friends and strangers, as well as imagination, in selecting the combination of faults and failings that best serve the plot, then assign them to a character. Sometimes the process works. Often it doesn’t.

When your characters fail to bring a story to life, you’ve failed to bring the characters to life. Conceiving of, and breathing life into, characters is probably the hardest, loneliest task you will ever face as a writer. When you make your characters out of pieces you collect from different people in your life and memory, you’re engaging in a profoundly incarnational act. Still, unless you grant those characters loving tolerance— giving them the opportunities to discover how they move, what they want to do, and how they want to do it—they will forever walk around stiff and wooden, awaiting or obeying your instructions.

I’m not suggesting that you let your characters write themselves. The author must create characters. But once incarnated, a character with some autonomy will be ten times more likely to engage the reader than will the character whose creator keeps a death grip on her motives, actions, and speech. The story with characters manipulated in the service of a pre-existing plot may entertain its readers, but it will never move them.

As a reader I want to feel, not think. You can have your main character stuck in a puddle of Super Glue on a railroad track with the express bearing down, and I won’t feel a thing if I haven’t come to care about him. Smash! He’s dead—so what? Unless I, the reader, have something to lose too, the character’s fate is unimportant to me, and my engagement in the story is minimal. What can you do to make readers care about the characters in your stories? Where does this magical incarnation begin? I think it begins with love. The reader’s relationship with the characters can only grow out of the writer’s relationship with those characters.

On avoiding over-explanation.

To an author who tells readers to much–with the best of intentions.

You have a lot of hard work ahead of you. The biggest task may be getting rid of what shouldn’t be in the novel. At the top of that list would be explanations to the reader, which come in the form of interior monologue, dialogue, and narration. And very often, what’s being explained is already perfectly clear to the reader. Writing is a form of communication, and writers have an understandable but unfortunate urge to make things clear. I say “unfortunate” because when you make something clear that readers can figure out on their own, you sacrifice a powerful way to engage them at a deeper level in your story.

Here’s how it works. Let’s say we read interior monologue that tells us Pie is smitten with Alex, or interior monologue that tells us Alex is smitten with Pie. We already know they’re attracted to each other, so we feel patronized. That feeling distances us at least a little from their unfolding romance. But suppose neither character expresses these thoughts directly. Suppose we see them together, listen to their dialogue, pick up subtle hints that suggest they’re attracted to each other, and come to the conclusion that whether either of them realizes it or not, they’re falling in love. At this point we’re involved in the story at a deeper level because we’ve invested a little of ourselves in it. Which is exactly what you want.

You have explanations of Pie and Alex’s feelings, explanations of fanatical Muslim philosophy and religious ideals, explanations of terrorist aims, and so on—very little, in fact, happens or is felt in this novel that isn’t pointed out or explained to the reader. (“Bob was angry, and Fletch was desperate.”) Sometimes explanations are necessary; more often, they’re not. If you stripped away most of the explanations, this novel would with that change alone become a much better book.

On a common misstep in a novel’s first chapter.

A tip for novelists on what to avoid.

The most common mistake we find writers making, albeit with the best of intentions, is to open their novels with some kind of information—exposition—rather than with a scene, something that happens. (Or by pulling the reader’s attention from an opening scene to explain it in some fashion.)

This is often deliberate, the idea being that the more readers know about someone or something, the more likely they are to take an interest. But most readers are more inclined to take an interest in a story based on witnessing what characters do, say, and think than on what the writer tells them before they have a chance to see the characters in action. This is just one reason why it’s a good idea to begin with a scene, or a character facing a challenge. It’s also the principle underlying the most time-honored advice for the novice fiction writer: show, don’t tell.

_ _ _

From all of us at The Kill Zone, many thanks to Ross Browne at The Editorial Department for allowing a repost of The Editor Over Your Shoulder and all our good wishes for Renni’s retirement.