by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

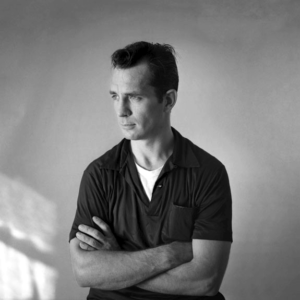

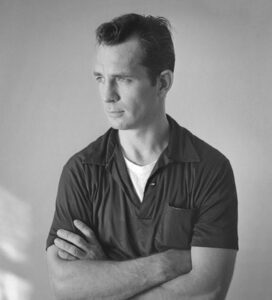

Jack Kerouac

Every college boy who wanted to be a writer back in the day when I trod the quad of my institute of higher education, went through a Jack Kerouac phase. This usually followed a Hemingway phase. In my case, I went through both simultaneously, which will blow your mind, man.

Hemingway, master of lean prose; and Kerouac, who spilled words on paper like Pollock tossed paint on canvas. Both authors had the added attraction of a personal brand—Hemingway, the man’s man, running with the bulls; and Kerouac, the “angel-headed hipster” driving freely across America in search of beatitude, with a jazz soundtrack.

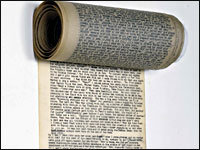

Kerouac (1922-1969) was dubbed the bard of the Beat Generation for his novel, On the Road (1957). He famously typed it on a 120-foot-long scroll of paper so he wouldn’t have to stop his flying fingers. In three weeks, fueled by Benzedrine and coffee, Kerouac produced the first draft of the book that made him famous. I do not recommend this method.

A second novel, The Dharma Bums (1958) cemented his reputation.

After that, in the humble opinion of your scribe, his prose became increasingly unreadable. No doubt his drinking had something to do with it—booze killed him at the age of 47.

He once typed out his writing advice, and from the looks of it he was, perhaps, stimulated. Fasten your seatbelt:

- Scribbled secret notebooks, and wild typewritten pages, for yr own joy

- Submissive to everything, open, listening

- Try never get drunk outside yr own house

- Be in love with yr life

- Something that you feel will find its own form

- Be crazy dumbsaint of the mind

- Blow as deep as you want to blow

- Write what you want bottomless from bottom of the mind

- The unspeakable visions of the individual

- No time for poetry but exactly what is

- Visionary tics shivering in the chest

- In tranced fixation dreaming upon object before you

- Remove literary, grammatical and syntactical inhibition

- Like Proust be an old teahead of time

- Telling the true story of the world in interior monolog

Okay, pause to catch breath. Yes, Kerouac was a “wild” “crazy dumbsaint” writer. Because of that, some of the prose in On the Road is exquisite. Like this oft quoted passage:

…and I shambled after as usual as I’ve been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes “Awww!”

But I can’t let #5 go without comment. The form of his later books seems to me to get increasingly messy (experimental) like the floor of a VW microbus driven across country by the Merry Pranksters. I think his “spontaneous prose” worked best in On the Road and The Dharma Bums because those already had a structure—they are really autobiography with the names changed, and much of the material was already in Kerouac’s journals. He was recording his experiences, not making up fiction.

- The jewel center of interest is the eye within the eye

- Write in recollection and amazement for yourself

- Work from pithy middle eye out, swimming in language sea

- Accept loss forever

- Believe in the holy contour of life

- Struggle to sketch the flow that already exists intact in mind

- Don’t think of words when you stop but to see picture better

- Keep track of every day the date emblazoned in yr morning

- No fear or shame in the dignity of yr experience, language & knowledge

- Write for the world to read and see yr exact pictures of it

- Bookmovie is the movie in words, the visual American form

- In praise of Character in the Bleak inhuman Loneliness

- Composing wild, undisciplined, pure, coming in from under, crazier the better

- You’re a Genius all the time

- Writer-Director of Earthly movies Sponsored & Angeled in Heaven

This all reads more like a window into Kerouac’s writer-mind than, say, an outline for a writing workshop. But there is one takeaway I might recommend.

I think the pursuit of writing gems, of style that elevates certain moments in your novel, is worth it. Maybe now more than ever what with AI cranking out colorless, soulless prose. Want to stand out in the tsunami of AI-generated cr*p? This is one way to do it.

What I do when I come to a moment of intense emotion is start a fresh document and begin “wild…pure…typewritten pages” telling “the true story of the world in interior monolog.” I type without “literary grammatical and syntactical inhibitions” to get to “bottomless from bottom of the mind.” I stay “submissive to everything, open, listening.”

When I’m done I’ll have 250 – 500 words of be-bop prose rhapsody, “swimming in language sea.” From that I can select, rearrange, tweak, and choose the best parts. Maybe even just one sentence, but that sentence will be choice.

So did any of these “tips” resonate with you? Blow as deep as you want to blow.