Jordan Dane

@JordanDane

On Monday, my lovely TKZ blogmate Clare Langley-Hawthorne had a post called “Losing the Past” where she discussed the state of the historical. I must admit I’ve been intimidated from trying to write an historical. The research seemed daunting, not to mention the world building and dialogue challenges, but I’ve always loved classic literature set in a historical time period made into movies, like Little Women, Pride and Prejudice, Wuthering Heights, David Copperfield, and Jane Eyre. There is something very compelling about taking a peek into the past to see the cultures, classes, location settings, and period clothing. Whether in a book or on screen, it’s a beautiful escape to a different time and place. Historicals aren’t dying out, they’ve become the new black if they’re reimagined into something fresh.

Lately I’ve become enthralled by TV period pieces, especially if the writing and storytelling are solid and the visuals and world building are memorable. Shows that have pulled me in are: Fox’s Sleepy Hollow, BBC’s Ripper Street, and Showtime’s Penny Dreadful. I watch other shows for different elements towards my writing, but these shows have influenced me into crossing the line of my comfort zone. I firmly believe, for me, that I must seek out projects to push my perceived limits. I think I learn more about myself when I do it. The only limit to any writer is the limit of their own imagination.

So when I was recently asked to contribute to a time travel anthology (with an amazing group of authors), I accepted with great enthusiasm (even though it scared me). I accepted the challenge because of my love for these three shows and my desire to push my writer limits. I wanted to share these feature film quality shows with you to see if they stir your imaginings as writers for inventive plots, attention to detail on world building and research, and the fearlessness of the creative mind to combine ideas that may not connect easily.

SLEEPY HOLLOW – The motto at Sleepy Hollow these days is “Embrace the Ridiculous.” Show creators and the talented writers have thrown together very unlikely elements to create what’s been called WTF TV. On paper, the pitch for the show would’ve sounded absurd – Washington Irving adaptations of Headless Horseman and Rip Van Winkle, mixed with Revelations in the Bible and the Four Horsemen of the apocalypse and historical conspiracies from the Revolutionary War. Icabod Crane is reimagined as a Revolutionary War hero and Revelations “witness” who arises from his secret grave at the same time as the Headless Horseman (aka Death) starts a killing rampage in the quiet town of Sleepy Hollow. The battle of good versus evil has found a home. Crazy, yet it works. The added touch of humor to this “man out of time” story makes Icabod a very endearing character. There’s tongue in cheek humor and the show is notably very ethnically blended. Sleepy Hollow is making history in more ways than its flashbacks.

SLEEPY HOLLOW – The motto at Sleepy Hollow these days is “Embrace the Ridiculous.” Show creators and the talented writers have thrown together very unlikely elements to create what’s been called WTF TV. On paper, the pitch for the show would’ve sounded absurd – Washington Irving adaptations of Headless Horseman and Rip Van Winkle, mixed with Revelations in the Bible and the Four Horsemen of the apocalypse and historical conspiracies from the Revolutionary War. Icabod Crane is reimagined as a Revolutionary War hero and Revelations “witness” who arises from his secret grave at the same time as the Headless Horseman (aka Death) starts a killing rampage in the quiet town of Sleepy Hollow. The battle of good versus evil has found a home. Crazy, yet it works. The added touch of humor to this “man out of time” story makes Icabod a very endearing character. There’s tongue in cheek humor and the show is notably very ethnically blended. Sleepy Hollow is making history in more ways than its flashbacks. RIPPER STREET is set in Victorian London right after Jack the Ripper left his mark. Fear runs high that the monster will return. The shows are tightly written, very emotional, and there is great sensitivity to social issues of the time that reflect on those same issues today. Another thing I love about Ripper Street is the portrayal of early forensics and crime scene analysis. Many scenes are laughable (ie surgical operations done in the open without sterilization or proper care for infection) yet accurate for the time period. Costumes are stunning and the street settings are vivid with great care for detail.

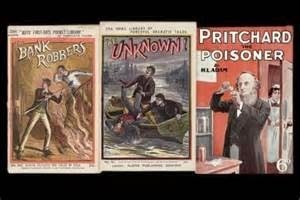

RIPPER STREET is set in Victorian London right after Jack the Ripper left his mark. Fear runs high that the monster will return. The shows are tightly written, very emotional, and there is great sensitivity to social issues of the time that reflect on those same issues today. Another thing I love about Ripper Street is the portrayal of early forensics and crime scene analysis. Many scenes are laughable (ie surgical operations done in the open without sterilization or proper care for infection) yet accurate for the time period. Costumes are stunning and the street settings are vivid with great care for detail.  PENNY DREADFUL – The show title of Penny Dreadful comes from history, the name given to paper pamphlets filled with terrifying stories. Such stories (also known as Penny Blood, Penny Awful, & Penny Horrible) plus stage performances of the genre were the rage in London during the Victorian time period. They were printed on cheap pulp paper and aimed at working class adolescents. Fear abounded and made fertile ground for when Jack the Ripper wreaked havoc on the streets.

PENNY DREADFUL – The show title of Penny Dreadful comes from history, the name given to paper pamphlets filled with terrifying stories. Such stories (also known as Penny Blood, Penny Awful, & Penny Horrible) plus stage performances of the genre were the rage in London during the Victorian time period. They were printed on cheap pulp paper and aimed at working class adolescents. Fear abounded and made fertile ground for when Jack the Ripper wreaked havoc on the streets. Penny Dreadful is an homage to literary horror and classic monsters of the time: Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde, etc. What I love about Penny Dreadful is the intense world building in every scene. The details of lush sets and gorgeous costuming and the use of practical literary monsters (not animated computer generate imagery). The horror is visceral.

Penny Dreadful is an homage to literary horror and classic monsters of the time: Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde, etc. What I love about Penny Dreadful is the intense world building in every scene. The details of lush sets and gorgeous costuming and the use of practical literary monsters (not animated computer generate imagery). The horror is visceral.

Here is Dr Victor Frankenstein slaving over his “creature” in secret. The scene where Victor lays eyes on his living creature (and the creature sees his creator for the first time) is an unforgettable moment where the viewer holds a breath to watch the touching intimacy. Everything about this show speaks to me of good writing, solid storytelling, and memorable characters in classic conflict. Visually stunning. It’s a feast for the eyes, mind, and heart.

Here is Dr Victor Frankenstein slaving over his “creature” in secret. The scene where Victor lays eyes on his living creature (and the creature sees his creator for the first time) is an unforgettable moment where the viewer holds a breath to watch the touching intimacy. Everything about this show speaks to me of good writing, solid storytelling, and memorable characters in classic conflict. Visually stunning. It’s a feast for the eyes, mind, and heart.

For Discussion: What shows stir your writer imaginings? Have they ever influenced you to write a genre you’ve never tried before?