On November 1, 2010, I was a reluctant founder of a critique group that was designed to help a group of professional writers better. Everyone lived in Northern Virginia, so we could meet in person, and since I had the biggest basement (and a Big Boy Job at the time, which put constraints on my ability to come home and head out again) we agreed to meet at my house. In my rumpus room, as it were. Thus was born the Rumpus Writers, aka Rumpi.

Since then, Donna Andrews, Art Taylor, Ellen Crosby, Alan Orloff, and I have met every month, with 100% attendance by everyone. That’s 138 meetings. The madness of the pandemic drove us to Zoom, but the record remains. Among the five of us, we have published (or have under contract) 92 books, 53 of which came out since we started getting together. In addition, we’ve written and published 109 short stories and edited 12 anthologies.

Collectively, we have been nominated for 55 major industry awards, of which we have one 36. Awards and nominations include: Edgar, Derringer, Agatha, Lefty, Toby Bromberg, Anthony, Barry, Library of Virginia People’s Choice, Romantic Times Readers Choice, Dilys, Macavity, Thriller, Shamus, Alex, Mary Higgins Clark and (believe it or not) the Gourmand World Cookbook Award.

Full disclosure: I was resistant to joining this group back in 2010 for several reasons. First, I am loathe to share unfinished writing with anyone. I didn’t understand the point of wasting other people’s time reading something that I already know is not up to snuff. Second, groups consisting of busy people tend to fall apart quickly. People don’t take their commitments seriously and I feared that the group would devolve into a massive time suck.

I didn’t really know any of these other authors until our first meeting. I had crossed paths a couple of times with Donna Andrews, and had chatted a couple of times with Ellen Crosby, but that was the extent of it. I made my concerns clear on our very first meeting. Not only were they well received, they were shared by everyone. That’s when we made the commitment that we would never miss a meeting. We’d figure out a way to get together once per month, come hell or high water. So seriously have we taken this commitment that there’ve been a few times when no common dates were available in a given month, so we’ve doubled up the meetings on the previous or subsequent month. There’s never been a twelve-month period when we haven’t met 12 times.

Format

The meeting starts at 7 pm. Read: 18:59:60. Every meeting starts with news of both the personal and business variety. The news is sprinkled with a hefty serving of gossip, too, but there’s an ironclad rule that nothing said leaves the room. Given recent circumstances in the news, we are officially more secure and honorable than Supreme Court clerks.

The chatting lasts for about an hour, and then it’s time to get to the business of critiquing. In turn, we read aloud from that week’s submission. Then, there’s a round-robin of input and we move on to the next submission. It’s rare that everyone has something to read on any given night, but it happens from time to time. Most submissions are in the range of 12-15 pages, but they’ve gone as high as 30+ pages. I think I am the record holder on a complete short story, but I needed to know if the payoff actually paid off.

Rules of Engagement

This one’s pretty easy. We’re honest without being snarky. One of my most frequent comments is, “Nothing happened in that scene.” It’s easy to do. You get caught up in exposition or dialogue and action gets lost. A comment I hear about my own work more often than I’d like is, “That emotion felt unearned.”

Then there’s the occasional knife to the heart: “That whole thing just didn’t work for me.”

Occasionally, there’s disagreement between us when offering a critique of a member’s work and we talk through it.

The target of the critique remains silent, taking it in until the end, when it’s fine to seek further input.

Pre-Validation Means A Lot

I think a large part of the group’s success is driven by the fact that none of us has anything to prove. We’re successful as authors, we’ve got established audiences, and we don’t seek abject approval (though it is always welcome). After all of this time, we have grown accustomed to each other’s voices on the page, and every one of us routinely violates the rules that we’ve heard in conferences and such are inviolable. Most of the time, those violations work for the story, or are a part of the author’s style.

What pre-validation does in a group like this is eliminate the need for forced praise before getting down to the business of what doesn’t work. We all know and respect that we’re capable writers. As such, we are also able to choose for ourselves which bits of advice we’re going to take, and which we’re going to ignore. When the meetings end, nobody feels bruised, and the friendships remain intact.

What Does This Mean For Writers Seeking Critique?

Over the years, I’ve sat in on critique sessions among amateur authors, and they all make me squirm. Attendees often are far more interested in hearing how brilliant they are than how to make things better. On the opposite end of the spectrum, there are the writers who are convinced they suck and therefore never process the good stuff they hear. Then there are the competing egos and genres, where the MFA graduate insists that the mystery or romance that someone else has written isn’t literary enough, or the genre writer who thinks a literary piece doesn’t work.

All too often, feelings get thrashed and no one has a good time.

I tell people who are looking for honest critique that almost all external input is harmful unless you have a strong sense of yourself as a writer. You need to find an honest neutral gear in your creative self where you are able to absorb the compliments and the criticisms with equal cynicism. Accept if only for the sake of argument that the other parties are coming from an honest place, but don’t assume that the reader who liked the piece is more accurate in his assessment that the one who did not.

As I’ve written in this blog before, the fact that the person with the critique bears the title of teacher does not imply infallibility. Sometimes, in the grand scheme of things, they can be flat-out wrong. On the other hand, they could be brilliant. How are you to tell the difference? I have no idea.

Now to you, TKZ family. Have you belonged to a critique group? How did it work out for you?

Two months ago, we completed our move to West Virginia, which was two years in the making, the final 7 months of which was in a tiny apartment in an urban part of Northern Virginia. In moving into the new place I designed my office around the reality of video-oriented promotional opportunities. My office in the previous house was designed such that my desk was in front of a pretty bay window that looked out onto the neighborhood. I enjoyed having all that light coming in over my shoulders while I worked, but it made for a terrible video backdrop. As a consequence, I did all my Zooming from the bar in my basement. It looked cool, but was not appropriate for all audiences.

Two months ago, we completed our move to West Virginia, which was two years in the making, the final 7 months of which was in a tiny apartment in an urban part of Northern Virginia. In moving into the new place I designed my office around the reality of video-oriented promotional opportunities. My office in the previous house was designed such that my desk was in front of a pretty bay window that looked out onto the neighborhood. I enjoyed having all that light coming in over my shoulders while I worked, but it made for a terrible video backdrop. As a consequence, I did all my Zooming from the bar in my basement. It looked cool, but was not appropriate for all audiences. Because I can do what I need to do from my desk, I have the advantage of a second screen on which I can see the people I’m talking to without looking down, or, in the case of videos for

Because I can do what I need to do from my desk, I have the advantage of a second screen on which I can see the people I’m talking to without looking down, or, in the case of videos for  With the publication of

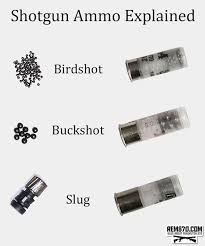

With the publication of  Shotguns also give you many options in terms of ammunition, and you should base your choice on a number of factors, not the least of which is where you live. (See above.)

Shotguns also give you many options in terms of ammunition, and you should base your choice on a number of factors, not the least of which is where you live. (See above.) When most people think “shotgun”, I believe they see the venerable 12-gauge shoulder buster that is featured in cop shows. Deployed properly, it’ll definitely do a number on the bad guy, but an apartment dweller needs to give serious consideration to the size of the shot and power of the loads he’s using. One of the commenters on Sue’s post on Monday posited the use of a 12 gauge slug against an intruder. Um, no. Not unless he’s fifty yards away and looks like an attacking grizzly bear.

When most people think “shotgun”, I believe they see the venerable 12-gauge shoulder buster that is featured in cop shows. Deployed properly, it’ll definitely do a number on the bad guy, but an apartment dweller needs to give serious consideration to the size of the shot and power of the loads he’s using. One of the commenters on Sue’s post on Monday posited the use of a 12 gauge slug against an intruder. Um, no. Not unless he’s fifty yards away and looks like an attacking grizzly bear. In most circumstances, even 00 (“double-aught”) buckshot is too hot for home defense. Every trigger pull of 00 buck launches 9 to14 .33 caliber pellets down range at 1,700 feet per second, give or take. It will drop whatever you hit, and at short ranges will likely pass right through your target with little reduction in speed. I think that a .410 shotgun loaded with #4 shot (.24 caliber pellets) is a better choice. It’s got far less recoil, but plenty of umph to stop your intruder. Even the hotter versions of birdshot will take the invader out of commission, and will pose less chance of collateral damage.

In most circumstances, even 00 (“double-aught”) buckshot is too hot for home defense. Every trigger pull of 00 buck launches 9 to14 .33 caliber pellets down range at 1,700 feet per second, give or take. It will drop whatever you hit, and at short ranges will likely pass right through your target with little reduction in speed. I think that a .410 shotgun loaded with #4 shot (.24 caliber pellets) is a better choice. It’s got far less recoil, but plenty of umph to stop your intruder. Even the hotter versions of birdshot will take the invader out of commission, and will pose less chance of collateral damage. If the shotgun in your closet is already a 12 gauge, consider “short loads”, which have considerably less powder, and therefore lessen the hazards to your neighbors.

If the shotgun in your closet is already a 12 gauge, consider “short loads”, which have considerably less powder, and therefore lessen the hazards to your neighbors. Well, let’s see.

Well, let’s see.

Last week, I had the honor of spending an hour or so with David Temple on his excellent podcast,

Last week, I had the honor of spending an hour or so with David Temple on his excellent podcast,