On Monday, Sue Coletta posted a gonzo good post on setting up a plan to prevent/cope with a home invasion. She called it “Easy Prey Dies First” and the title says it all. If you haven’t read it, you should follow the link and do it now.

In her pulse-pounding opening, Sue painted a picture of waking up at 2 a.m. to the sound of breaking glass followed by the sound of footsteps on the stairs. What would I do?

I’ll get to my answer below, but let’s think through some options first. Given that violence never comes with a Playbill, we can never know until after the fact if the stranger in your house is there to take your life or merely to steal your stuff. Where I live, in West Virginia, it’s a distinction without a difference. We’re a true castle doctrine state. More than a few states, however, punish a homeowner for a violent encounter unless an intruder poses a direct, definable threat to their lives–and then only after they have made a reasonable effort to flee and seek shelter.

In my former home state of Virginia, lethal force was considered justified inside the home, but only if there was a direct threat. If a resident hears a noise downstairs, away from the sleeping area, the law tips against him if he seeks out a suspected intruder and confronts the bad guy. Prosecutors will charge the homeowner with manslaughter because, in the eyes of the law, the homeowner started the fight. The bad guy was merely stealing stuff.

These are important points to consider when you’re putting your home invasion plan together. It would suck to go to prison for defending your home with violence and then see your family be sued into poverty by the bad guy’s relatives.

Now, let’s assume that going to guns is an option. There are other supremely important considerations:

Are all of your family members accounted for?

One of the strongest arguments against having a gun in the house is the reasonable likelihood that it will be used accidentally against a family member. It would be beyond tragic for a late homecoming or a 2 a.m. trip to the kitchen to result in homicide. In the circumstance posited by Sue in her post, the shattering of glass pretty much takes those mistakes off the table.

I believe the solution here is to educate and train all your family members on the safe handling and use of the firearms you have in the house. Most shooting ranges have a young shooter program.

Involve the entire family in your plan.

Specifically, what do you want your kids to do? My suggestion if they’re young is to tell them that if they hear or see dangerous things in the middle of the night, they should yell for help, but never, under any circumstances should they open their bedroom door. If the kids are older, consider giving them a more active role in the plan.

And about bedroom doors . . . Closed doors add over five minutes of survival time in a housefire. Of the times I pulled dead kids out of fires, 100% slept with their doors open. Correlation is not causation, but the physics of fire behavior is pretty clear on this. A topic for a future post, perhaps.

Is calling for help an option?

We’ve all heard the cynical wisdom that when seconds matter, police are only minutes away. There’s a lot of truth in that, but it’s always–ALWAYS–a good idea to place a call or text to 9-1-1 to get law enforcement on the way. It establishes for the record that a crime is in progress and it gets officers on the way.

In rural areas and in some understaffed cities, response times can be disturbingly long–a fact that puts more pressure on the home defender.

Running away is always the best solution.

A punch not thrown never hurts. But our hypothetical scenario has the bad guy on the stairs, which define my way out of the house. Now that I’m halfway through my sixth decade, a jump from the second floor is not in the cards. But if you can get away, do so. And stay away. Your legal standing gets really murky when you leave a place of safety to return to a fight. In many states, that makes you the aggressor and the bad guy the defender.

Again, remember to include the kids in your plan. Generally, society frowns on parents who flee a home invader and leave their children behind to fend for themselves. Be sure to have a designated rally point somewhere away from the house so you can count noses after the house is empty.

Sheltering in place is bad advice.

Feel free to disagree and yell at me, but I believe this with all my heart. When you hide in a closet or in a corner, your surrender all maneuverability and grant all the advantage to the bad guy.

If violence is your solution, try to bring the fight to the bad guy.

This brings me back to Sue’s original scenario. Stairways are God’s gift to home defenders, the best possible place to have your violent confrontation with the bad guy because he has no place to go. He’s stuck in a chute with little to no maneuvering room and no ability to establish a good fighting stance. I would move as quickly as possible to meet him at the top of the stairs, looking down on him, and there we’d have a very serious discussion about his future.

I tell people that they should consider the stairs to the sleeping level to be their Alamo. That’s where they make their stand. As long as the bad guy is rummaging around the house where there are no occupants, there’s plausible deniability that he’s just after stuff. Once he hits the stairs, though, the only reasonable assumption is that he has capital crimes in mind.

Choose your weapons.

Hand-to-hand combat is for young people, and then only for those who have been trained on fighting skills. Without that training, if the confrontation comes to the laying on of hands, you’re going to lose. Knives are an especially bad idea because not only are you fighting at bad-breath distance, you’re going to get cut. As for impact implements like baseball bats golf clubs, consider the logistics of a full swing in a narrow space. It’s not going to end well.

Guns.

It’s my post so you knew it had to come to guns, right? People often ask what I think is the firearm to use against home invaders. (Much of what follows will get you in deep trouble with the law if you live in certain states. Check your state and local regulations,)

Spoiler: There is no right answer as to which weapon is best, but irrespective of your ultimate choice, it’s all on you to make sure you know how to use it in a way that does not pose a risk to innocent people. This is a lot less complicated an equation when you live in a rural environment, a quarter mile away from your nearest neighbor, than it is when you live in an urban apartment complex. After the bullet passes through your bad guy, it’s going to find another target, whether it’s the stud behind the wall or the sleeping baby next door.

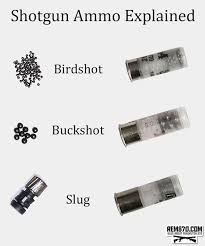

I am a fan of shotguns as home defense weapons. When you’re sleep addled and operating in low light, the spread of pellets out of a smooth bore weapon gives you the greatest likelihood of hitting the bad guy. The farther you are from your intended target, though, the higher the likelihood that some of the pellets are going to miss the bad guy and seek mischief behind him.

Shotguns also give you many options in terms of ammunition, and you should base your choice on a number of factors, not the least of which is where you live. (See above.)

Shotguns also give you many options in terms of ammunition, and you should base your choice on a number of factors, not the least of which is where you live. (See above.)

When most people think “shotgun”, I believe they see the venerable 12-gauge shoulder buster that is featured in cop shows. Deployed properly, it’ll definitely do a number on the bad guy, but an apartment dweller needs to give serious consideration to the size of the shot and power of the loads he’s using. One of the commenters on Sue’s post on Monday posited the use of a 12 gauge slug against an intruder. Um, no. Not unless he’s fifty yards away and looks like an attacking grizzly bear.

When most people think “shotgun”, I believe they see the venerable 12-gauge shoulder buster that is featured in cop shows. Deployed properly, it’ll definitely do a number on the bad guy, but an apartment dweller needs to give serious consideration to the size of the shot and power of the loads he’s using. One of the commenters on Sue’s post on Monday posited the use of a 12 gauge slug against an intruder. Um, no. Not unless he’s fifty yards away and looks like an attacking grizzly bear.

In most circumstances, even 00 (“double-aught”) buckshot is too hot for home defense. Every trigger pull of 00 buck launches 9 to14 .33 caliber pellets down range at 1,700 feet per second, give or take. It will drop whatever you hit, and at short ranges will likely pass right through your target with little reduction in speed. I think that a .410 shotgun loaded with #4 shot (.24 caliber pellets) is a better choice. It’s got far less recoil, but plenty of umph to stop your intruder. Even the hotter versions of birdshot will take the invader out of commission, and will pose less chance of collateral damage.

In most circumstances, even 00 (“double-aught”) buckshot is too hot for home defense. Every trigger pull of 00 buck launches 9 to14 .33 caliber pellets down range at 1,700 feet per second, give or take. It will drop whatever you hit, and at short ranges will likely pass right through your target with little reduction in speed. I think that a .410 shotgun loaded with #4 shot (.24 caliber pellets) is a better choice. It’s got far less recoil, but plenty of umph to stop your intruder. Even the hotter versions of birdshot will take the invader out of commission, and will pose less chance of collateral damage.

If the shotgun in your closet is already a 12 gauge, consider “short loads”, which have considerably less powder, and therefore lessen the hazards to your neighbors.

If the shotgun in your closet is already a 12 gauge, consider “short loads”, which have considerably less powder, and therefore lessen the hazards to your neighbors.

This is really scary stuff to contemplate, but I think it’s important to do so. Know that your plan will never be perfect, so it’s probably folly to rehearse the physical movements of a confrontation, but I think it’s worthwhile to think through the emotions and the intent. How long are you going to lay in bed talking yourself out of believing what you know to be true? How much time are you going to lose trying to remember where you stashed the ancient pistol you inherited five years ago from Uncle Charlie?

I get that many people think that this level of planning–even the discussion itself–is silly because the chances of this ever happening are miniscule, and I’ll stipulate that the numbers are on the side of the naysayers. But by the same logic, there’d be no need for smoke detectors or seat belts.

The scenario Sue posted guarantees that somebody’s going to get seriously hurt. I’d rather it not be me or my family.

Well, let’s see.

Well, let’s see.

Last week, I had the honor of spending an hour or so with David Temple on his excellent podcast,

Last week, I had the honor of spending an hour or so with David Temple on his excellent podcast,