A couple of weeks ago, I posted here about my great fortune to score an ongoing talk radio gig on WRNR Radio/TV 10 in Martinsburg, West Virginia. It’s strictly a talk format, with Rob Mario as host, and then two co-hosts, of which I am one a couple of times per week.

It’s interesting sitting on the other side of an interview. Having done more than a few of them over the years as the interviewee, being the interviewer has changed my perspective a bit. In recent weeks, we’ve interviewed a few authors. I thought I’d share some lessons I’ve learned that you might find helpful if you find yourself in the position to promote your book–or to promote anything for that matter.

Know ahead of time what the format will be.

On our show on Eastern Panhandle Talk Radio, all interviews are 22-25 minutes long, free from commercial interruption. That’s unusual in my experience for broadcast radio and television. Normally, the broadcast format runs 7-10 minutes, which requires an entirely different approach.

In shorter interviews, be prepared to deliver the vaunted elevator pitch, where you get right down the details of the book. There likely won’t be a lot of give-and take between you and the host. If there is, that’s great. Just don’t anticipate it.

Longer interviews, on the other hand, are much more conversational. If you launch right into the elevator pitch and stay with it, there won’t be much interaction with the hosts, and you run the risk of leaving little to talk about during the rest of the spot.

Anticipate the common questions and have stories to tell.

You know the low-hanging fruit: Where did the idea come from? What kind of research did you do? Which of your books is your favorite? What authors do you read? Tell us about the story.

The best interviews are with people who tell the stories behind the stories. Keep it light-hearted and entertaining. If you can make your book resonate with current events or current times, that’s always a good thing.

Another trait of great interviews is that they are conversational. Try to forget that YOU’RE ON THE RADIO!!! and concentrate more on having a casual conversation with the person across from you in the studio or on the other end of the phone call.

There’s a good chance that “radio” means TV, too.

In these days of video streaming, many (most?) radios stations also have a live feed to Facebook or other social media sites. Plan accordingly to avoid that awkward jammies and bed-head television exposure.

Send promotional materials ahead of time.

Remember that your interview is but one tiny slot inserted into a busy broadcast. People will not have had time to read your book, certainly on short notice. Be sure to send along a synopsis of the story, along with a short bio.

Suggested questions are always welcome because they give the interviewer a clue about what topics you are most prepared to cover.

In your promotional materials, be sure to include a headshot of you and the cover of your book. If there is a TV/Facebook live element, this is essential. One of the most recent interviews sent along a single image that is a combined cover and author photo. I’m going to steal that idea.

Avoid qualitative assessments of your own work.

This might just be my own bugaboo, but I find it vastly unprofessional for an author to tell the world how funny, inspirational or exciting his own work is. Just as on the page, show, don’t tell. Let your enthusiasm for the project sell the book for you.

Mention the title. A Lot.

In a standard interview, you’ll be introduced as the author of [Your Book Title], and then again as such at the end of the interview. Remember that every time you refer to your baby as “my book” or “it” you’re missing an opportunity to burn the title into listeners’ and viewers’ brains.

Always close with your contact and social media information.

Rudeness is never okay, but don’t be afraid to be a little aggressive, especially at the end of an interview. Consider:

” . . . Thanks for coming on the show, John.”

“Real quick, please visit my website, John Gilstrap dot com for anything you want to know about me or my books.”

You’re on the show to market a book, so don’t be shy about marketing your book.

What say you, TKZ family? Have I missed anything?

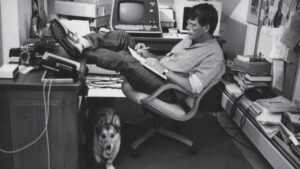

When I was growing up, immersed in dreams of one day becoming a writer, I romanticized what the process must be like. Where would one go to imagine new worlds and create new adventures? Movies romanticized the whole process, and I bought into it. Then I saw this now famous picture of a then less-famous Stephen King in his writing space. It seemed so . . . ordinary. Yet at the same time it seemed very special. The dog under his feet is a nice touch. This is a guy with a job. And his creative space is . . . an office. Just an office. But of course, it’s more than that. It’s Stephen King’s office. (As you’ll see below, it turns out that I was not the only budding young writer who was impressed by the photo.)

When I was growing up, immersed in dreams of one day becoming a writer, I romanticized what the process must be like. Where would one go to imagine new worlds and create new adventures? Movies romanticized the whole process, and I bought into it. Then I saw this now famous picture of a then less-famous Stephen King in his writing space. It seemed so . . . ordinary. Yet at the same time it seemed very special. The dog under his feet is a nice touch. This is a guy with a job. And his creative space is . . . an office. Just an office. But of course, it’s more than that. It’s Stephen King’s office. (As you’ll see below, it turns out that I was not the only budding young writer who was impressed by the photo.) Our move to West Virginia presented a unique opportunity to design an office as an office–as opposed to a purloined bedroom. Now that I think about it, I suppose there’s not a lot of difference between the two. I wanted lots of light and direct access to the outdoors. That door leads to a deck that overlooks the woods. The orange helmet on the left end of the bookcase belonged to my father. A closer look will show that it’s quite banged up from the helicopter crash he survived on the deck of the USS Forrestal in 1959. The two yellow helmets are mine from the two jurisdictions where I ran fire and rescue. (I had to turn my white lieutenant’s helmet back in when I left.) Since the house is now run by a 12-pound ball of fur named Kimber, chew toys and water bowls litter the floor of every room.

Our move to West Virginia presented a unique opportunity to design an office as an office–as opposed to a purloined bedroom. Now that I think about it, I suppose there’s not a lot of difference between the two. I wanted lots of light and direct access to the outdoors. That door leads to a deck that overlooks the woods. The orange helmet on the left end of the bookcase belonged to my father. A closer look will show that it’s quite banged up from the helicopter crash he survived on the deck of the USS Forrestal in 1959. The two yellow helmets are mine from the two jurisdictions where I ran fire and rescue. (I had to turn my white lieutenant’s helmet back in when I left.) Since the house is now run by a 12-pound ball of fur named Kimber, chew toys and water bowls litter the floor of every room. Here it is from a different angle. This is messier than it normally is, but a pinky swear is a pinky swear. Note the studio grade microphone and the webcam–a new bit of ubiquity in office photos, I’ve found. All of those Gilstrap books stacked on the far end of the bookcase are the background for Zooming and YouTube videos (when I start shooting them again). The opened journal you see on the desk is one of many that I have stacked around the place (each novel gets a new journal). That’s where I scratch my way through difficult parts of the story that are somehow resistant to being typed. That green chair in the corner used to belong to me. Now it’s Kimber’s day bed and she gets very annoyed if I move the blanket from where she left it.

Here it is from a different angle. This is messier than it normally is, but a pinky swear is a pinky swear. Note the studio grade microphone and the webcam–a new bit of ubiquity in office photos, I’ve found. All of those Gilstrap books stacked on the far end of the bookcase are the background for Zooming and YouTube videos (when I start shooting them again). The opened journal you see on the desk is one of many that I have stacked around the place (each novel gets a new journal). That’s where I scratch my way through difficult parts of the story that are somehow resistant to being typed. That green chair in the corner used to belong to me. Now it’s Kimber’s day bed and she gets very annoyed if I move the blanket from where she left it. When we moved out of Fort Lauderdale five years ago, it meant big downsizing. As some wag said (might have been George Carlin): You spend the first half of your life accumulating stuff and the second half getting rid of it. We now live half the year in Tallahassee and half in Traverse City, Michigan. We don’t have the luxury of an extra “office” space anymore, so I store everything on line and cart my laptop around wherever the spirit moves me. Often it’s the sofa, but more likely my local coffee shop or after 4, the Traverse City Whiskey Co. where they make a mean whiskey sour. On spectacular days like today, the balcony will do.

When we moved out of Fort Lauderdale five years ago, it meant big downsizing. As some wag said (might have been George Carlin): You spend the first half of your life accumulating stuff and the second half getting rid of it. We now live half the year in Tallahassee and half in Traverse City, Michigan. We don’t have the luxury of an extra “office” space anymore, so I store everything on line and cart my laptop around wherever the spirit moves me. Often it’s the sofa, but more likely my local coffee shop or after 4, the Traverse City Whiskey Co. where they make a mean whiskey sour. On spectacular days like today, the balcony will do. I’m fortunate to have a bedroom dedicated to me. This is my workspace, which doesn’t show my cluttered closet space or bookshelves. The desk is also a little less cluttered than usual, since the request for the photo came on Friday, and I clear my desk on Thursday for the housekeeper. The stacks of paper next to the printer and behind the monitor represent my method of ‘housekeeping.’ The stacks will eventually topple over, and I’ll attempt to separate the wheat from the chaff.

I’m fortunate to have a bedroom dedicated to me. This is my workspace, which doesn’t show my cluttered closet space or bookshelves. The desk is also a little less cluttered than usual, since the request for the photo came on Friday, and I clear my desk on Thursday for the housekeeper. The stacks of paper next to the printer and behind the monitor represent my method of ‘housekeeping.’ The stacks will eventually topple over, and I’ll attempt to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Attached are two photos of my office from different angles. The Holy Hands on my desk were made and blessed by a Cherokee chief. They hold tiny replicas of my Mayhem Series. Both gifts from a couple (readers) who said I touched their lives.

Attached are two photos of my office from different angles. The Holy Hands on my desk were made and blessed by a Cherokee chief. They hold tiny replicas of my Mayhem Series. Both gifts from a couple (readers) who said I touched their lives.  Most of the crows, as well as the crow dreamcatcher hanging above, were also gifts from readers. All mean a lot to me. Constant reminders of why I write.

Most of the crows, as well as the crow dreamcatcher hanging above, were also gifts from readers. All mean a lot to me. Constant reminders of why I write. Here’s my office. I’m most comfortable surrounded by books, and many of these mysteries are signed by friends. The box with the white rug is for my cat, Vanessa. She “helps” while I work.

Here’s my office. I’m most comfortable surrounded by books, and many of these mysteries are signed by friends. The box with the white rug is for my cat, Vanessa. She “helps” while I work. Here’s a shot of my mind lab. Brief description: “My creative place is a combination of old and new. Side-by-side, I have a Windows 11 laptop with audio/visual recording devices next to a retro 1920s private detective office with stuff like a pristine vintage typewriter and a cool rotary phone that’s tweaked to work in the digital age. Fun place. BTW, that filing cabinet is stuffed full of books.”

Here’s a shot of my mind lab. Brief description: “My creative place is a combination of old and new. Side-by-side, I have a Windows 11 laptop with audio/visual recording devices next to a retro 1920s private detective office with stuff like a pristine vintage typewriter and a cool rotary phone that’s tweaked to work in the digital age. Fun place. BTW, that filing cabinet is stuffed full of books.” My desk, with microphone and sound foam. To the left, pics of Stephen King (with legs on desk), Ed McBain, and John D. MacDonald, all telling me to stop whining and write. My coffee mug with WRITER on it, which I bought a few days after I decided I had to try to become a writer. And a file folder for my first drafts.

My desk, with microphone and sound foam. To the left, pics of Stephen King (with legs on desk), Ed McBain, and John D. MacDonald, all telling me to stop whining and write. My coffee mug with WRITER on it, which I bought a few days after I decided I had to try to become a writer. And a file folder for my first drafts. Forgive me as I begin this week’s post with some shameless self-promotion. This is Launch Week for the latest in my Jonathan Grave thriller series (#14!). It’s called

Forgive me as I begin this week’s post with some shameless self-promotion. This is Launch Week for the latest in my Jonathan Grave thriller series (#14!). It’s called  My name is Kimber. I am a Cavaston–a mix of Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and Boston Terrier. My new parents drove all the way up to Pennsylvania to pick me up on February 15. It was cold and I was scared.

My name is Kimber. I am a Cavaston–a mix of Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and Boston Terrier. My new parents drove all the way up to Pennsylvania to pick me up on February 15. It was cold and I was scared. I had to go to the doctor for a checkup during my first week at the apartment. The doctor was nice, but there’s not a lot of privacy. They stuck me with needles and squeezed me a lot, but they let me eat spray cheese out of a can while they did it, so I didn’t mind all that much.

I had to go to the doctor for a checkup during my first week at the apartment. The doctor was nice, but there’s not a lot of privacy. They stuck me with needles and squeezed me a lot, but they let me eat spray cheese out of a can while they did it, so I didn’t mind all that much. Not everybody recognizes the origins of my name. John tells me it’s the same as one of his favorite pistols. One day, when we were visiting the new house before we moved in and the heat wasn’t turned on yet, I got cold and climbed inside of his vest. After this picture was taken, John called me his quick-draw puppy.

Not everybody recognizes the origins of my name. John tells me it’s the same as one of his favorite pistols. One day, when we were visiting the new house before we moved in and the heat wasn’t turned on yet, I got cold and climbed inside of his vest. After this picture was taken, John called me his quick-draw puppy. These days, we’re all moved into the new house and the construction is over with–well, mostly. John complains that the master bedroom closets still aren’t finished. I like living in the country more than I liked living in the apartment. Out here, I get to pee and poo outside instead of on the little pads that I never really hit. (Apparently, you’re supposed to have your back legs on the pad, too. Who knew?)

These days, we’re all moved into the new house and the construction is over with–well, mostly. John complains that the master bedroom closets still aren’t finished. I like living in the country more than I liked living in the apartment. Out here, I get to pee and poo outside instead of on the little pads that I never really hit. (Apparently, you’re supposed to have your back legs on the pad, too. Who knew?) Country living can be scary. I was playing in the woods just a few days ago and I saw something that looked like it wanted to play with me, but not in a good way. It kept hissing and trying to bite me. I’m really fast, though. I barked and barked, and finally, John came out to see what was happening. The stranger hissed and tried to bite him, too. He got very stern and told me to go back into the house. A few minutes later, I heard a really loud noise. I haven’t seen the stranger since.

Country living can be scary. I was playing in the woods just a few days ago and I saw something that looked like it wanted to play with me, but not in a good way. It kept hissing and trying to bite me. I’m really fast, though. I barked and barked, and finally, John came out to see what was happening. The stranger hissed and tried to bite him, too. He got very stern and told me to go back into the house. A few minutes later, I heard a really loud noise. I haven’t seen the stranger since. I think John’s really happy that I’m around the house. All day long, he sits in a chair in front of a folding thing with buttons on it, but I’m tall enough now that I can jump right up onto the buttons and help him push them. He pretends not to like me doing that, but he always ends up playing with me. Maybe not the first time I jump up, or the second, but sooner or later, he gives in and plays. He said something about not being able to say no to my face.

I think John’s really happy that I’m around the house. All day long, he sits in a chair in front of a folding thing with buttons on it, but I’m tall enough now that I can jump right up onto the buttons and help him push them. He pretends not to like me doing that, but he always ends up playing with me. Maybe not the first time I jump up, or the second, but sooner or later, he gives in and plays. He said something about not being able to say no to my face.