By John Gilstrap

Yesterday, February 21, 2023, marked the launch date for White Smoke, the third book in my Victoria Emerson trilogy about the courage and inspiration of an unwilling leader who helps to rebuild society on the heels of a brief by devastating nuclear war. Quoting Chris Miller’s review from BestThrillerBooks.com:

Yesterday, February 21, 2023, marked the launch date for White Smoke, the third book in my Victoria Emerson trilogy about the courage and inspiration of an unwilling leader who helps to rebuild society on the heels of a brief by devastating nuclear war. Quoting Chris Miller’s review from BestThrillerBooks.com:

Gilstrap champions Victoria Emerson through grace and grit. She defies post-apocalyptic America expectations by delivering hope and unity in uncertain times. On the outside she’s the epitome of what every person should look up to and garner their strength from, while on the inside things are probably not the same. She is the model citizen as she forces everyone to come to a realization that the old world is gone and it is up to them to make the best of the future. She is rock solid while leading from the front and you can tell the character development has been a pained one for her, but something that the people of Ortho have come to depend on.

Victoria Emerson is a leader for a reason, and she doesn’t sugarcoat the truth. The equity that she puts into Ortho and its people is just the same that she puts into her kids and their responsibilities. This is nothing short of what kind of people we hope come to lead our country in rough times, while the real world still has a say in things. White Smoke has action, emotion, and every bit of unease you could ask for.

Pretty cool, eh?

As part of the marketing push for the release, Kensington Books asked me to write an essay to be inserted in various newsletters for distribution to booksellers. When I finished that project, I realized that I had something to share here on the Killzone Blog. It’s not exactly about writing, but I think it provides insight into how hopes, fears and concerns can morph into a story. Here we go:

Preparing For the Unthinkable

I’ve never admitted this in public before: Given the depth and breadth of political

divisions in the United States, I believe that the probability of massive civil unrest is higher today than it has been since 1861. I’m less concerned about international conflict of the nature represented in the Victoria Emerson trilogy, but there’s an unsettling amount of crazy going around.

I hope I’m wrong about all of the above, but beginning in 2017, my wife and I started

planning for the unthinkable. Without going into detail, we live in the country now, largely away from other people, in a place where abundant furry protein sources wander through my property every day. My freezer and pantry are well stocked, but if things go bad, we have a hedge against starvation. Our water comes from a well so we’re no longer dependent upon a municipal bureaucracy to survive. My next step is to become a competent gardener—which, if last summer is any indication, remains a distant if not impossible dream.

All these changes have bought me is time. By being prepared, I can wait out the worst of civil unrest.

Is Survival Important To You?

That’s not a trick question. I grew up in the crucible of the Cold War as a Navy brat. If

the balloon went up, Dad would be off to war and my mother proclaimed her intent to stand outside to be vaporized as early as possible. She wanted nothing to do with the deprivations of a postapocalyptic world.

I don’t share that mindset, though I do understand it. The life we live now, as hard as it

might be, is easy-peasy compared to life after a catastrophe. The constructs of good, dependable, honest governance are the only elements that keep our feral nature at bay. It wasn’t that long ago that people were shooting each other over toilet paper and hand sanitizer. Imagine how ugly things would get if the stakes involved whose baby gets the last vial of lifesaving medication.

The question on the table is, How far are you willing to go to ensure your family’s

survival? Your answer can be neither right nor wrong, but it does require some introspection.

Getting your head right.

Disasters come in all sizes, from a fire in your basement to an intruder in your home;

from an active shooter in the shopping mall to major weather events. Regardless of the scale of the disaster, certain priorities always apply:

1. Stuff doesn’t matter. Whether it’s your new Lamborghini or your grandma’s book of family recipes, stuff is just stuff. It doesn’t have a heartbeat, and it’s not worth sentencing your kids to an orphanage to save it from being harmed.

2. You and your family are all that matters. In the Victoria Emerson books, I refer to the concentric circles of relationships. When bad stuff happens, everything and everyone is secondary to the survival of my family. That might seem selfish at first glance, but it’s not. Fact is, everybody practices the concept, even if they don’t think of it that way.

3. Pets are important, too. But they’re not people.

4. Escape is always better than conflict. Every fight you walk away from is a victory,

whether it’s from an intruder in your hallway or a hurricane barreling toward your house.

5. If conflict is unavoidable, bring it fast and in a big way. And train your kids. If

someone touches them inappropriately or tries to grab them, train them to gouge out the attacker’s eyes with their thumbs or bite off their fingers. All you need to do is buy enough time to run away (see #4 above). Teach them to scream. Our message to our son when he was growing up was that it is better to die on the street than to get shoved into a car. I still believe that to be true.

6. Have an evacuation plan. What do you want your kids to do if they wake up to the

sound of a smoke detector? (Hint: wandering the halls of your burning house looking for Mom and Dad is a bad plan.)

7. Have a plan to reunite. During an emergency, you don’t want to waste valuable escape time looking for each other. Spend those critical first seconds seeking safety. Once the hazard is behind you, know where you can go to find family members from whom you became separated. If they are not present at that spot when you arrive, let the emergency responders know. In the Victoria Emerson series, this planning takes a long view. Because Victoria was separated from one of her children, they had a standing plan in place that if something catastrophic happened while they were separated, they all knew to gather at Top Hat Mountain for their eventual reunion.

Now that your head is in the right place, what’s next?

The first step is to prepare yourself, your family, and your pantry for tough times. Few

people have Rambo’s knowledge of survival skills, but a quick search will reveal dozens of books on the subject. Outdoor Life Magazine compiled as good a list of references as I’ve seen. I haven’t read them all, but I’ve read a few and they’re all helpful and interesting.

Do you plan to evacuate or shelter in place?

If you plan to evacuate, where are you going to go? If your first choice is to drive 500

miles to Grandma’s house, think harder. Weather events and civil unrest make roads impassable. Is there a place you can hike to, even if it would take a few days? You’ll need food, shelter, and a means to carry or create clean drinking water. The challenges of a long hike in the winter are entirely different than those same challenges in the summertime.

If you expect to shelter in place, plan to do so without electricity or running water. In an

urban environment, you don’t want to confront the desperate neighbors who are flocking to the grocery store to strip their shelves, so commit yourself to keeping five days’ worth of basics in your pantry. Even if it’s cans of tuna and jugs of water, it’s enough to keep you alive and away from marauders on the street.

How do you plan to protect yourself and your family from others?

In the immediate aftermath of the government’s emergency declarations regarding the

pandemic of 2020-22, panicked Americans flocked to gun stores to purchase unprecedented numbers of firearms. Many of those buyers made their purchases out of fear that the normal mechanisms of law enforcement would be unable to protect them from harm.

Most of those firearms are still out there in the hands of people who have received

precious little training in their use. More than a few will see taking stuff from you as an integral part of their survival plan. That’s a recipe for someone having a very bad day.

My plan for my family is to stay away from it all and mind my own business, in hopes

that others will do likewise. If you’re on the scumpti-fifth floor of a high-rise that is situated among other high-rises, your situation will likely be more complicated. I don’t have the answers that will work for you, but these are things worth thinking about and planning for.

What say you, TKZ family? Have you peeked down this rather frightening rabbit hole? To the degree you’re willing to share, what planning have you done for the unthinkable?

I’ve stated here before that social media in general is my Achilles’ heel. I deeply don’t understand Twitter, which seems bloated and toxic, and I don’t photograph nearly enough of my life to drive my Instagram account. My social media safe space is my Facebook author page, where I’ll post a few times a week with interesting tidbits and photos–leaning heavily into dog pix because Kimber is the cutest creature on the planet. I don’t post book news unless it is timely and new, so that leaves me with the daily chores, pleasures and ironies of life.

I’ve stated here before that social media in general is my Achilles’ heel. I deeply don’t understand Twitter, which seems bloated and toxic, and I don’t photograph nearly enough of my life to drive my Instagram account. My social media safe space is my Facebook author page, where I’ll post a few times a week with interesting tidbits and photos–leaning heavily into dog pix because Kimber is the cutest creature on the planet. I don’t post book news unless it is timely and new, so that leaves me with the daily chores, pleasures and ironies of life.

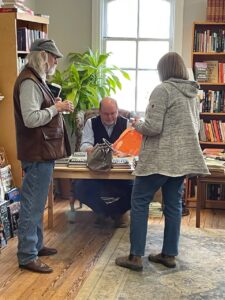

In the case of the signing at Four Seasons Books, since I’m new to the community, I bought a gorgeous charcuterie platter from

In the case of the signing at Four Seasons Books, since I’m new to the community, I bought a gorgeous charcuterie platter from  I always bring extra books–especially for the first event with a new bookseller. It’s always hard to estimate how many books is the right number for a signing, and for reasons that make all the sense in the world, booksellers often underestimate. If they run out of their stock, they can dig into my author’s copies, which they sell at list price and then just backfill my copies with the next order from their distributor. This saves a lot of embarrassment.

I always bring extra books–especially for the first event with a new bookseller. It’s always hard to estimate how many books is the right number for a signing, and for reasons that make all the sense in the world, booksellers often underestimate. If they run out of their stock, they can dig into my author’s copies, which they sell at list price and then just backfill my copies with the next order from their distributor. This saves a lot of embarrassment. Yesterday, February 21, 2023, marked the launch date for White Smoke, the third book in my Victoria Emerson trilogy about the courage and inspiration of an unwilling leader who helps to rebuild society on the heels of a brief by devastating nuclear war. Quoting Chris Miller’s review from

Yesterday, February 21, 2023, marked the launch date for White Smoke, the third book in my Victoria Emerson trilogy about the courage and inspiration of an unwilling leader who helps to rebuild society on the heels of a brief by devastating nuclear war. Quoting Chris Miller’s review from  Stealth Attack hit the stands in July, 2020, which means I wrote it in 2019. When I read the email, I was confused. I couldn’t remember anything in that book that resembled anything that Mary Anne found so offensive. Recognizing that I am getting no younger, and that my memory isn’t necessarily as acute as it used to be, I pulled the book from my shelf and re-read Chapter 17.

Stealth Attack hit the stands in July, 2020, which means I wrote it in 2019. When I read the email, I was confused. I couldn’t remember anything in that book that resembled anything that Mary Anne found so offensive. Recognizing that I am getting no younger, and that my memory isn’t necessarily as acute as it used to be, I pulled the book from my shelf and re-read Chapter 17.