There’s a buzz about the internet that the traditional publishing market is dying, and that the most reliable route to authorial success is through some form of self publishing. In my experience, the rumors are in large measure perpetuated by people and bots who stand to make money from frustrated authors who want to see their words in print and are willing to pay for editing and publishing “services” that suck cash and provide no guarantees.

The argument as I hear it.

The days of Maxwell Perkins and like minded star makers are long gone. No publisher (herein after synonymous with “traditional publisher”) is willing to develop young talent. Either the manuscript arrives at the transom fully formed and ready to publish, or it will be rejected.

Agents are no longer taking on new clients. Instead, they concentrate on their current stable of authors, who make sure that the doors to the publishing industry are closed to newcomers.

The entire industry is prejudiced against (depending on the perpetuator of the rumors) white people, people of color, men, women, gays, straight people, old people or young people, and about any other demographic slice that has chosen to feel oppressed on any given day.

For those authors who have found the magic string to pull to gain access to an agent and then on to a publisher, disappointment awaits. Either the selected publisher will pay too much for a book that doesn’t earn out, thus dooming the author to a painfully short career, or they will pay a mere pittance that will have no meaningful impact on the author’s finances.

And oh, the financial abuse! For every book sold, the publisher keeps as much as 90%, and of the paltry 10% given to the author, one-fifth of the amount goes to the author’s agent. When Amazon will let an author keep 70% (?) of the cover price, who would even consider a real publisher?

The evidence is plain and clear: Advances are shrinking for everyone, and the Big Five are getting smaller every day. Clearly, that’s the sign of the industry’s impending death.

One would be a fool to even consider offering their book to a publisher.

Reality as I see it.

First, a brief reminder of where I come from: I sold my first novel, Nathan’s Run, in 1995. By the time it hit the stands, I had already sold pub rights to my second book, At All Costs. Both were sold for astonishing seven-figure advances and neither earned out. Not even close. Since then, there’ve been 26 more books, with at least two more under contract.

The Max Perkins editing model died long before I joined the publishing scene, and I’ve been around since the days when query letters were sent in envelopes that contained an SASE, and manuscripts were shipped via FedEx at something like $25 a pop. That’s when I learned that only bad news came in the SASE. Good news came via phone call. Even then, the burden lay with the writer to submit a near perfect manuscript to agents who requested to see a sample. Then, as today, the easiest answer to a newbie trying to enter the entertainment business, the easiest answer was/is no. Who would want to establish a long-term relationship with someone unprofessional enough to submit flawed work as their first impression?

Then and now, overworked editors depend on agents to serve as gatekeepers at two important levels. First, there’s the quality of the writing. Without a good story that is well told, there’s no good product to mold into a better product. (There’s never been hope for ill-conceived or poorly written stories).

Second, agents make sure that excellent manuscripts go only to editors who are looking for that kind of story. When a trusted agent tells an editor, “I’m giving you a 24-hour exclusive on this story before I submit it wide,” all other work gets shoved aside for the editor to read and make an offer (or not). Publishing continues to be a relationship business.

When a manuscript is accepted by a publisher, editing is less about wordsmithing than it is about project management. Once everyone is happy with the story, the editor champions that manuscript all the way through the cover design, marketing and publicity efforts. For the record, no author in the history of the world has been pleased with their books’ marketing or publicity plans.

NOTE: First novels are in large measure author auditions. Authors who work to promote their own works, make speeches and show an active interest in the advancement of their own career will see their publicity budgets grow with time.

Now, as then, agents and editors are starving for new talent, and champing at the bit to take on new authors. The crippling problem now that didn’t exist in my early days, is email. Back in the day (Good Lord, I can hear my old man voice), the sheer inconvenience and expense of submitting via mail served as a form of natural selection. And before that–as recently as the 1980s–a new draft meant retyping the entire manuscript. Talk about a barrier to entry!

Now, each agenting day reopens the valve for a tsunami of under-cooked, ill-conceived and poorly-executed submissions overloading their email boxes. I’m talking really awful, terrible drek. New authors demonstrate a shocking lack of respect for these professionals’ time. As always, the easiest answer is no. A yes has to be earned.

But according to the interwebs, nobody needs an agent anyway. There are plenty of resources they can pay to publish their terrible work on ebook platforms.

The nightmare of huge advances

I’m not going to pad the truth here. When HarperCollins and Warner Books recognized the magnitude by which they’d overestimated the marketability of Nathan’s Run and At All Costs, my career took took a kick to the doo-dads. But I got to keep the money. Let’s call that a silver lining.

And I kept writing, churning out character-driven thrillers. I was able to build on the various starred reviews of those first books, and I found publishers who were willing to hang in there because I was willing to take advances that hovered around 2% of the news-making paydays. Audiences grew, and as they did, so did the advances.

Nowadays, I won’t take an advance that I can’t earn out within 8 weeks of publication. That frees up lots of cash to be used in promotion and marketing. Over time, as a backlist grows, it acts as a kind of annuity, rendering the advance as more of a symbolic payment.

Many aspects of the good old days never made sense.

All corners of the entertainment business are driven by significant egos, all of which need stroking. Big name editors are stroked by their own imprints, authors with book tours and big advances. The huge names in this industry never earn back their advances because much of their value lies in being among the authors published by the publishing house. Ninety-nine percent of book tours lose money for the publisher, but the loss is justified by the bragging rights.

Or, so it has been for generations.

I think the most critical element in the slow implosion of the Big Five is the fact that they are now owned and run by people who don’t particularly like books or publishing. Once acquired by mega companies, publishers become another profit center among dozens of other profit centers whose profit margins are much higher than that which is possible in the book biz. The last couple of years has seen countless big-name editors released and replaced by lesser editors who demand lower paychecks. Publicity, distribution and copy editing are routinely sourced out to freelancers who have no emotional tie to the companies who hire them or the authors they edit.

The stage is set for great things.

The ossification of the Big Five is creating tremendous opportunities for new authors and new publishers that exist because they like the business of producing books. My own publisher, Kensington, remains privately owned and thriving. Newcomers like Blackstone and Source Books are making great strides in taking on new and orphaned authors and turning profits at the same time. New publishing companies are opening their doors every week, it seems.

But with new opportunities comes a shift in the author-publisher paradigm. It’s expected now that authors understand that they are small business owners and therefore responsible for a solid percentage of their book’s success in the marketplace. Writing is becoming more of a team endeavor.

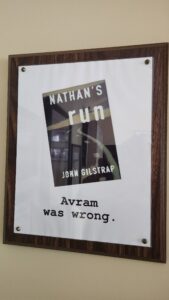

I wish I could say that I shrugged off his cruel dismissal–well, I did eventually, I suppose–but it took more years than I care to admit. Upon publication of Nathan’s Run, one of my classmates from that workshop gave me a heartwarming plaque that hangs in my office in clear view as I write this.

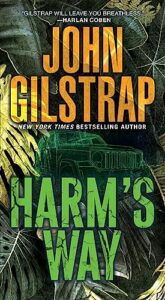

I wish I could say that I shrugged off his cruel dismissal–well, I did eventually, I suppose–but it took more years than I care to admit. Upon publication of Nathan’s Run, one of my classmates from that workshop gave me a heartwarming plaque that hangs in my office in clear view as I write this. First things first. As I write this, it’s Book Launch Day! Harm’s Way, the 15th entry in my Jonathan Grave thriller series drops today. In this story, Jonathan is summoned by FBI Director Irene Rivers to rescue someone special from the grips of a drug cartel that has taken a group of missionaries hostage in Venezuela. Once the team arrives, however, they discover trouble far more horrifying than a standard hostage rescue. When the first book in the series appeared in 2009, I never would have thought it would have the kind of legs that it has.

First things first. As I write this, it’s Book Launch Day! Harm’s Way, the 15th entry in my Jonathan Grave thriller series drops today. In this story, Jonathan is summoned by FBI Director Irene Rivers to rescue someone special from the grips of a drug cartel that has taken a group of missionaries hostage in Venezuela. Once the team arrives, however, they discover trouble far more horrifying than a standard hostage rescue. When the first book in the series appeared in 2009, I never would have thought it would have the kind of legs that it has.