So we all know how subjective an assessment of any novel can be – we see it all the time in conflicting book reviews, Amazon and Goodreads ratings, or, as demonstrated in every book group I’ve ever attend, the amazing array of reader reactions possible to the exact same book… Instinctively, I think we all know that our work cannot please everyone all the time. How then does a new writer know if the work he or she is producing is going to be of a standard that will attract an agent or editor’s interest? How (at the most basic level) do you know if you’ve written something that’s actually ‘good enough’ for publication?

Most writers I know suffer from a fair measure of self-doubt as well as ambition, and many, by their own account, are never totally sure when they complete a new draft whether others are actually going to like it. That’s where beta readers, critique groups and manuscript/first page critique sessions come in – these all provide writers with some initial feedback on their work. This is also where the thorn in every writer’s side comes in – subjectivity. We’ve all heard stories of agents and editors who didn’t like the next book a writer they previously loved produced, or books rejected dozens of times only to be picked up by that one elusive editor and nurtured to success. Remember how many times the first Harry Potter book was rejected only to then go on to be bestseller…well, many writers cling to that hope – but how to know when that hope is possibly true or, sadly, unfounded? Art by its very nature is subjective…so how is a new writer to gauge the success of their current WIP without being driven crazy by the spectre of ‘subjectivity’ ?

I admit I am just as plagued by self-doubt as the next writer and even when I think something I’ve written is pretty good I’m never sure anyone else is going to think the same…so when working with my own beta readers/critique partners I adopt the following approach in order to keep my sanity:

- I ask for both an overall assessment as well as specific feedback on elements in the story that are critical ( e.g. POV, narrative flow and character) or areas where I know I am weakest (hello, plot and structure!). This enables my readers to pinpoint some elements that may not work as well as others (and hopefully avoid the vague “I’m not sure why I didn’t like that bit…” kind of response).

- I look for consistency of the same feedback. If everyone feels like the POV isn’t as strong as could be, then there’s probably merit in considering reworking it. If only one person doesn’t like a particular element, I may be less sure…and I may need to probe their response a little deeper.

- I accept the likes and dislikes of my beta readers. All of mine love historical fiction but some have a preference for lighter or darker mysteries, while others aren’t really into speculative or fantasy elements…and so I tailor my feedback requests to take this into account.

- I reach out to new beta readers/critique partners that represent the readers I am targeting in my current WIP. If it’s a children’s book for example, I think children should give their feedback, not just adults.

- I realize the limitations of any feedback and try to critically reappraise my own work as well. Just after I’ve finished a draft I’m usually too close to the material to take a step back and process its overall merits. I need to give myself time and space so I can re-evaluate my work – because often your own gut feel is just as important.

- I try to accept that failure is the only means to achieving ultimate success. No matter the blow to one’s ego, sometimes we have to admit it that something doesn’t work and move on. I strongly believe that each ‘failure’ is an important learning step on the path to success (even if it does suck sometimes!)

What about you? How do you deal with the thorny ‘subjectivity’ issue when it comes to feedback for your own work? What process do you use to gain the confidence that your work really is ready…in terms of being ‘good’, ‘marketable’ or ‘publication ready’?

Inspired in part by this week’s New York Times ‘Bookends’ article (

Inspired in part by this week’s New York Times ‘Bookends’ article (

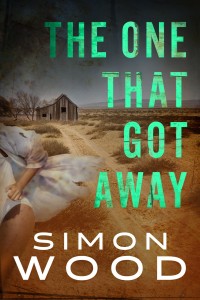

abducted them and their situation is grim. Their futures can be measured in minutes, not years. That would be enough of a conflict for most writers. Not for me though. I have to take that awful scenario and make it worse. Zoë has to make a horrible decision—make a futile attempt to save Holli or use Holli as the distraction to help her escape. Zoë makes the hard decision—she escapes with her life and has to live with the guilt and shame of that single act of self-preservation.

abducted them and their situation is grim. Their futures can be measured in minutes, not years. That would be enough of a conflict for most writers. Not for me though. I have to take that awful scenario and make it worse. Zoë has to make a horrible decision—make a futile attempt to save Holli or use Holli as the distraction to help her escape. Zoë makes the hard decision—she escapes with her life and has to live with the guilt and shame of that single act of self-preservation. eries and rigs that prevented noxious chemicals and gases that come up with the crude oil from getting into the atmosphere. That kind of work meant dealing with contingencies. If a valve failed, what was the bypass? If the bypass failed, what was the bypass’ bypass? It was all part of designing to multiple levels of failure. It’s no different than my flying experiences. Aircraft are very cleverly thought out. If one system fails, there’s another that can double for it. You’re taught to be able to fly with most of your gauges out of operation knowing that just a couple of things will guide you to safety. All this has taught me to view the world as a worst case scenario. In fact, a lot of my stories have been born by looking an aspect of the world and thinking of all the ways it can go wrong. I look at a bad idea and turn it into an apocalyptic nightmare.

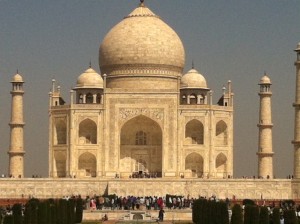

eries and rigs that prevented noxious chemicals and gases that come up with the crude oil from getting into the atmosphere. That kind of work meant dealing with contingencies. If a valve failed, what was the bypass? If the bypass failed, what was the bypass’ bypass? It was all part of designing to multiple levels of failure. It’s no different than my flying experiences. Aircraft are very cleverly thought out. If one system fails, there’s another that can double for it. You’re taught to be able to fly with most of your gauges out of operation knowing that just a couple of things will guide you to safety. All this has taught me to view the world as a worst case scenario. In fact, a lot of my stories have been born by looking an aspect of the world and thinking of all the ways it can go wrong. I look at a bad idea and turn it into an apocalyptic nightmare. I returned from an amazing trip to India all the more excited about possible future projects not just because my ‘on the ground’ research was more fruitful than I expected, but because I’d been able to experience that critical connection to history that will (I hope) provide the window I need to reimagine the past. I’d felt this connection once before, in Venezuela, and it provided me the impetus for writing my first Ursula Marlow mystery, Consequences of Sin.

I returned from an amazing trip to India all the more excited about possible future projects not just because my ‘on the ground’ research was more fruitful than I expected, but because I’d been able to experience that critical connection to history that will (I hope) provide the window I need to reimagine the past. I’d felt this connection once before, in Venezuela, and it provided me the impetus for writing my first Ursula Marlow mystery, Consequences of Sin. One of the most surprisingly things to come out of my research was that the place I had originally believed would be the initial setting for my story (Hyderabad) was totally displaced by my experiences in another city (Udaipur – photo to the right) and I saw quite clearly my characters inhabiting this landscape and not the one I had previously envisaged (only downside, a whole new set of history books to read!).

One of the most surprisingly things to come out of my research was that the place I had originally believed would be the initial setting for my story (Hyderabad) was totally displaced by my experiences in another city (Udaipur – photo to the right) and I saw quite clearly my characters inhabiting this landscape and not the one I had previously envisaged (only downside, a whole new set of history books to read!).