by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Earle Hyman

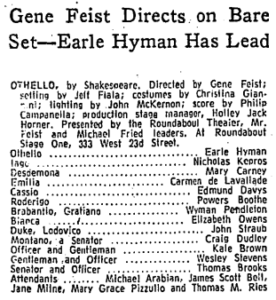

Last week we lost a very dear man. Earle Hyman was known to most people as Bill Cosby’s father on The Cosby Show. But he was so much more. An accomplished stage actor, he was one of the great Othellos.

I know because I got to watch him play the role night after night.

I was a young and hungry actor, freshly arrived in New York City and living at The Leo House on West 23d. Across the street at that time was the Roundabout Theater. I walked over there one day and asked for a job. I got one, pushing around scenery for the current production, Shaw’s You Never Can Tell.

As part of the deal, I got to audition for their upcoming production of Othello.

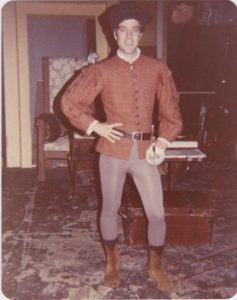

And I got the part! My first paid acting role! As … Attendant. No lines, but I didn’t care. I was doing Shakespeare Off-Broadway, in tights and everything!

Earle Hyman was Othello. Also in the cast was a young Powers Boothe as Roderigo.

And so we began rehearsals. I loved every minute of it, even though my part was just walking on, standing, and walking off. But when I was off, I’d listen. I’d listen to how Earle and Nick Kepros (Iago) did Shakespeare. Iago has some of the best lines in the entire canon, and I determined to play that role someday.

In fact, one night before the show I was sitting backstage with Earle. He was so generous to the young actors, down-to-earth and always willing to give advice. I mentioned I wanted to play Iago someday, and he said, “You’re perfect for it!”

In fact, one night before the show I was sitting backstage with Earle. He was so generous to the young actors, down-to-earth and always willing to give advice. I mentioned I wanted to play Iago someday, and he said, “You’re perfect for it!”

“I am?” I said, wondering if some nefarious part of my personality had leaked out.

“Oh, yes,” Earle said. “You have an open, honest face.” (This, mind you, was well before I went to law school.) He explained, “Othello calls him ‘honest, honest Iago.’ It’s wrong to play the part as an obvious villain.”

I then breezily but sincerely told him I was going to mount a production of Othello someday and play Iago, and that I wanted him to play the lead.

“I’ll do it!” he said.

A lovely man.

So the show opened and was well received by the Times. I continued to listen. I was something of a voice impersonator in those days. I’d crack up the cast by doing imitations of the various actors.

Then one night it happened. My big moment.

Now, to fully appreciate what I’m about to relate it is necessary that you know the classic film All About Eve. If you have not seen it and wish to be spared knowing the plot twist, you might want to skip to the last paragraphs of this post.

In brief, All About Eve is the story of a theater diva named Margo Channing (Bette Davis). A devoted young fan named Eve Harrington (Anne Baxter) comes to her and pours out her heart about loving the theater and idolizing Margo. This gets her a job as Margo’s assistant.

What we come to learn is that Eve Harrington has only one thought in mind—to displace Margo as the star of a new hit play. She underhandedly snags the understudy role. And then she sets in motion an elaborate scheme so Margo will be unable to make curtain one night.

Eve is a sensation, and from there turns her back on everyone who’s helped her as she ascends the stairway to stardom.

Back to Othello. One night, about an hour and half before curtain, a call comes in from the actor playing Montano—a minor role, but with significant lines. He was stuck in Brooklyn and wouldn’t be able to make the show. I can’t remember why, but I assure you I had nothing to do with it.

The stage manager was in a panic. There were no understudies. Then someone told him, “Jim knows the part. He knows all the parts.”

The stage manager rushed over to me and put his hands on my shoulders. “Do you? Do you really know the part?”

“What from the cape can you discern at sea?” I said, quoting Montano’s first line.

“You’re going on!”

On! Me! I was giddy as he spent twenty minutes with me on the stage, walking me through the blocking. I only half listened, for my other half was loop-quoting the Bard: “Yet heavens have glory for this victory!”

Then I was dismissed to go get ready for the performance.

As I entered the dressing room, everyone was already putting on makeup or getting into costume. The moment I appeared our Iago, Nick Kepros, in a voice dripping with droll amusement and loud enough for all to hear, said, “Well, well, if it isn’t Eve Harrington!”

The room exploded in laughter. It was the perfect line, brilliantly delivered.

So on I went.

Nailed it!

Though it was one night only and did not catapult me to stardom, it was supremely satisfying. I had spoken Shakespeare on a stage in New York! And received warm congratulations from the cast, including Mr. Earle Hyman.

All that to say, writer, be ready. The old saw about luck being the intersection of preparation and opportunity applies.

Be ready when you read. When you come across a passage that moves you or compels you to turn the page, ask yourself why that is so. Mark up the book with notes.

Be ready when you write. Listen to your book and the characters as they take on life. What are they telling you that you didn’t know before?

Be ready when you edit. By studying the craft and having tools that actually work, you become more adept at creatively fixing your manuscript.

Be ready with your elevator pitch. If anyone asks you what your book is about, you should be able to tell them in thirty seconds, and in a way that makes their eyes light up. (An elevator pitch formula may be found here.)

Do all that and you know what you’ll be ready for next? To “put money in thy purse!” (Iago, Act I, Scene 3.)

So what serendipitous event has happened in your own life? Were you ready for it?