WARNING: SPOILER ALERTS

Yesterday, I killed the dog.

I didn’t want to do it but it had to be done. The creature had been hanging around far too long and I had sort of grown to regret ever allowing it into my life. So I killed the dog.

I waited as long as I could — chapter twenty-two to be exact. But then I just typed the words and the mutt was gone. Now I have to endure the after-wrath. It won’t come for months because the book won’t be published until next year but I know it will come. There’s an unwritten rule in our genre that you never kill animals. Because if you do, your readers turn on you like, well, rabid dogs.

It’s not just dogs. It can be cats. I am a big fan of the British writer Minette Walters, read every book she put out. Until “The Shape of Snakes” and she had a character who tortured cats to death with duct tape. Repulsed, I threw the book across the room. I had seven cats at the time.

This rule about animals is not just limited to cats and dogs. It’s birds, hamsters, horses. I refused to see the movie “War Horse” until a friend assured me the horse didn’t die. And don’t get me started about what those damn pigs did to Boxer the Horse in “Animal Farm.”

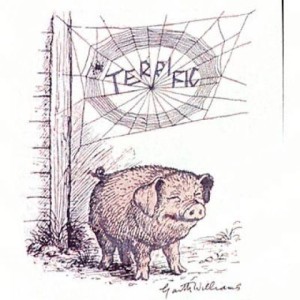

The killing of the good and innocent. It’s the toughest thing we writers do. I am often asked what books have influenced me most as a writer and my first answer is “Charlotte’s Web.” It taught me that yes, sometimes you just have to kill off a really good character for the sake of the story, even if it’s only a spider.

Is it harder if it’s a human being?

Why should a dog, a horse, a rat, have life,

And thou no breath at all? Thou’lt come no more,

Never, never, never, never, never!

That’s King Lear speaking. He’s grieving for the dead Cordelia. She was the good daughter, if you recall. Now Shakespeare had no qualms about killing off the good. (That’s why they called them tragedies.) We writers are still learning from him after all these years, especially those of us in the crime genre where death is the main machine in our plots.

I’ve been thinking hard about this lately. Not just because of the dog thing but because of “Downton Abbey.” When Matthew Crawley bought the farm on that country road my mouth dropped open. Damn! They killed the good guy! He’s never coming back. Unless Mary steps into the shower and declares that his death was just a dream.

I felt the same way when Bobby Simone did his Mimi bit on “NYPD Blue.” Ditto when Col. Henry Blake’s helicopter went down in “M*A*S*H.” And I was upset that Lane Pryce hanged himself in “Mad Men” before he had a chance to make things right in his sad life.

Is it different in novels? Do readers feel less invested than viewers? Or are the attachments they form in the pure ether of their imaginations even stronger than those forged by film?

Consider Charles Dickens. He delivered his novel “The Old Curiosity Shop” chapter by chapter to his fans and when he killed off his heroine, Little Nell, all hell broke loose. One critic wrote, “Dickens killed Nell just as a butcher would slaughter a lamb.”

Author Conan Doyle always wanted to kill off Holmes. (“I must save my mind for better things, even if it means I must bury my pocketbook with him,” he once grumbled.) When Doyle finally did Holmes in, thousands canceled their subscription to The Strand. Doyle eventually gave in and resurrected Holmes in “The Hound of the Baskervilles.”

Closer to home, a few years ago crime writer Karin Slaughter killed off one of her beloved characters. Readers were furious, many accusing her of doing it for the shock value and vowing to never pick up another one of her books again. Slaughter felt compelled to post an explanation on her website.

Readers take these things personally. At least they do if you, the writer, are doing your job. It broke my heart when Beth died in “Little Women.” I was mad at Larry McMurtry for weeks after he killed Gus in “Lonesome Dove.” It took me decades to understand why Phineas had to die in “A Separate Peace.”

In fact, I didn’t really get what Fowles was doing with that book until fairly recently when I finally got around to reading Joseph Campbell’s “The Hero’s Journey.” Finney, I realized, had to die so Gene could find a way to live.

I wish I could say that in those decades between “Charlotte’s Web” and “The Hero’s Journey” that I have learned how to the handle death of the good. That is what the best books are supposed to do, after all, teach us about such big questions. But I think I have become a better at dealing with death as a writer. So let me offer a few suggestions for anyone who is struggling with this.

Make it worth something. You must create a bond between the doomed character and the reader so when that character dies, it has value. The death has to propel the plot forward or affect the emotional arc of another character. Check out this stellar passage from one of my favorite books “Smiley’s People” by John le Carré.

Slowly, [Smiley] returned his gaze to Leipzig’s face. Some dead faces, he reflected, have the dull, even stupid look of a patient under anaesthetic. Others preserve a single mood of the once varied nature – the dead man as lover, as father, as car driver, bridge player, tyrant. And some, like Leipzig’s, have ceased to preserve anything. But Leipzig’s face, even without the ropes across it, had a mood, and it was anger: anger intensified by pain, turned to fury by it; anger that had increased and become the whole man as the body lost its strength.

The death has to be organic. Make sure there is enough time for the reader to come to know the character. The death may be a surprise but there should be a subtle feeling of foreshadowing about it. Lennie Small in “Of Mice and Men” strikes an empathetic chord with the reader. That’s why his death at the hands of his best friend George to spare him from a lynch mob, is so powerful.

Don’t do it to fix a weak plot. We’ve all read books where another corpse is dropped and we go “meh.” Mercifully, I won’t include any examples here.

Keep true to your book’s tone. How do you want your readers to feel about this? Fearful? Deep sense of personal loss? Generalized feeling of human tragedy? Maybe you want them to laugh. Yeah, can be appropriate. I can’t think of any book examples but here’s an image I can’t forget from “L.A. Law”: Villainess Rosalind Shays accidently stepping to her doom in that open elevator shaft.

Don’t preach. Let the readers make their own conclusions about what the death means. Don’t tack on one of those awful codas where the hero stands around telling us what truths he has learned. And don’t, for corn’s sake, have someone say something like, “well, I guess we should steer clear of cannibals in the future.”

Be sure of what you are doing. Unless you’re in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s league, you can’t undo a death. At least not without some silly deus ex machina thing. I mean, I am glad that Spock didn’t really die from radiation poisoning in the warp drive tube. But I thought his rebirth was cheesy. I recently read a really good mystery by a successful author and I am pretty sure that the character he killed off isn’t really dead. (Can’t tell you the title; the author would kill me). I hope I am wrong. I hope the character is dead because it feels truer to this writer’s voice. Which leads me to my final point…

Let the end make room for beginnings. Pay attention to the survivors in your story and make sure death affects their lives. Leave room for redemption. In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” what’s so disturbing about Tom Robinson’s death is its awful inevitably. After falsely being found guilty of rape, he tries to escape but is shot by prison guards. But are we left in despair? I don’t think so because through this experience, Jem and Scout are learning about the dark complexities of the adult world. And at the end, there is Jem, keeping Scout from squishing that little roly-poly bug. There is hope in his need to protect the most vulnerable. There is hope for us all.