by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

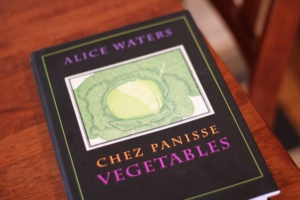

Whenever my wife and I travel to the Bay Area, we try to pop over to Berkeley and nosh at the noted bistro Chez Panisse. Overseen by its co-founder, executive chef Alice Waters, it is credited with popularizing the style of cooking known as California cuisine.

Whenever my wife and I travel to the Bay Area, we try to pop over to Berkeley and nosh at the noted bistro Chez Panisse. Overseen by its co-founder, executive chef Alice Waters, it is credited with popularizing the style of cooking known as California cuisine.

I’m no specialist in things culinary, but I know what I like. And I like California cuisine. It takes familiar foods and spices and combines them in a way that is not overpowering to the palate. It’s sort of like being in a park on a sunny California day, the temperature not overpowering, and lots of happy things going on around you.

Which brings me to the subject of originality. I connect it to Alice Waters by way of this passage from Theme & Strategy (Writer’s Digest Books) by Ronald Tobias:

We say we prize originality above all else in art. Originality is the artist’s brilliance, that indefinable something that is distinctly the artist’s and no one else’s. What gets lost in all that praise of individuality is that originality is nothing more than seasoning added to stock. Seasoning gives distinct flavor, its character or charm, if you will, and seasoning gives the distinct taste that immediately identifies the dish as unique. But we forget that the foundation remains the same, and that the chef and the diner both rely on that fact.

A chef’s genius is not to create a dish from original ingredients, but to combine standard ingredients in original ways. The diner recognizes the pattern established in the foundation of a baked stuffed turkey, and we look for the variation, the twist that will surprise and delight us. Perhaps it’s in the glaze or in the stuffing, something that makes that turkey different from all the other turkeys that came before it.

As you develop an idea for a story, start with the foundation, the pattern of action and reaction that is plot.

In my workshops I’m sometimes asked how to keep plot and structure from devolving into formulaic writing. My answer is similar to what Tobias says above. And what Alice Waters would say. You don’t cook an omelet with a watermelon. If I want an omelet, I want it made with eggs in a pan with some ingredients and spices. What those add-ons are and how they are proportioned make up the distinctiveness–the originality if you will–of the dish.

In the same way, structure is the eggs. It’s what readers expect from a story. They don’t want to be confused or frustrated. Of course, an author is free to write experimental fiction, which is also known by its unofficial name, Fiction That Doesn’t Sell.

But if you’re in this to make some dough, you’ll use familiar ingredients but you’ll spice them up with your unique brand of characterization, dialogue, and voice.

The late, great writing teacher Jack Bickham wrote the following in Scene & Structure (Writer’s Digest Books):

Mention words such as structure, form, or plot to some fiction writers, and they blanch. Such folks tend to believe that this kind of terminology means writing by some type of … predetermined format as rigid as a paint-by-numbers portrait.

Nothing could be further from the truth

In reality, a thorough understanding and use of fiction’s classic structural patterns frees the writer from having to worry about the wrong things, and allows her to concentrate her Imagination on characters and events rather than on such stuff as transitions and moving characters around, when to begin or open a chapter, whether there ought to be a flashback, and so on. Once you understand structure, many such architectural questions become virtually irrelevant — and structure has nothing to do with “filling in the blocks.”

Structure is nothing more than a way of looking at your story material so that it’s organized in a way that’s both logical and dramatic.

Don’t get ensnared by the ruinous idea that structure is the enemy of originality and this thing we call “story.” In fact, the opposite is true.

So become a great chef. Know your ingredients. Cook up a delicious tale by mixing the familiar with your unique blend of spices.

Your readers will eat it up.

What is your view of originality? What are some examples from writers you admire?