by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

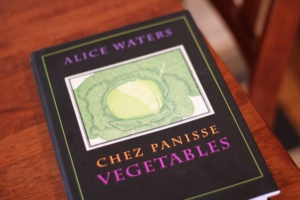

Whenever my wife and I travel to the Bay Area, we try to pop over to Berkeley and nosh at the noted bistro Chez Panisse. Overseen by its co-founder, executive chef Alice Waters, it is credited with popularizing the style of cooking known as California cuisine.

Whenever my wife and I travel to the Bay Area, we try to pop over to Berkeley and nosh at the noted bistro Chez Panisse. Overseen by its co-founder, executive chef Alice Waters, it is credited with popularizing the style of cooking known as California cuisine.

I’m no specialist in things culinary, but I know what I like. And I like California cuisine. It takes familiar foods and spices and combines them in a way that is not overpowering to the palate. It’s sort of like being in a park on a sunny California day, the temperature not overpowering, and lots of happy things going on around you.

Which brings me to the subject of originality. I connect it to Alice Waters by way of this passage from Theme & Strategy (Writer’s Digest Books) by Ronald Tobias:

We say we prize originality above all else in art. Originality is the artist’s brilliance, that indefinable something that is distinctly the artist’s and no one else’s. What gets lost in all that praise of individuality is that originality is nothing more than seasoning added to stock. Seasoning gives distinct flavor, its character or charm, if you will, and seasoning gives the distinct taste that immediately identifies the dish as unique. But we forget that the foundation remains the same, and that the chef and the diner both rely on that fact.

A chef’s genius is not to create a dish from original ingredients, but to combine standard ingredients in original ways. The diner recognizes the pattern established in the foundation of a baked stuffed turkey, and we look for the variation, the twist that will surprise and delight us. Perhaps it’s in the glaze or in the stuffing, something that makes that turkey different from all the other turkeys that came before it.

As you develop an idea for a story, start with the foundation, the pattern of action and reaction that is plot.

In my workshops I’m sometimes asked how to keep plot and structure from devolving into formulaic writing. My answer is similar to what Tobias says above. And what Alice Waters would say. You don’t cook an omelet with a watermelon. If I want an omelet, I want it made with eggs in a pan with some ingredients and spices. What those add-ons are and how they are proportioned make up the distinctiveness–the originality if you will–of the dish.

In the same way, structure is the eggs. It’s what readers expect from a story. They don’t want to be confused or frustrated. Of course, an author is free to write experimental fiction, which is also known by its unofficial name, Fiction That Doesn’t Sell.

But if you’re in this to make some dough, you’ll use familiar ingredients but you’ll spice them up with your unique brand of characterization, dialogue, and voice.

The late, great writing teacher Jack Bickham wrote the following in Scene & Structure (Writer’s Digest Books):

Mention words such as structure, form, or plot to some fiction writers, and they blanch. Such folks tend to believe that this kind of terminology means writing by some type of … predetermined format as rigid as a paint-by-numbers portrait.

Nothing could be further from the truth

In reality, a thorough understanding and use of fiction’s classic structural patterns frees the writer from having to worry about the wrong things, and allows her to concentrate her Imagination on characters and events rather than on such stuff as transitions and moving characters around, when to begin or open a chapter, whether there ought to be a flashback, and so on. Once you understand structure, many such architectural questions become virtually irrelevant — and structure has nothing to do with “filling in the blocks.”

Structure is nothing more than a way of looking at your story material so that it’s organized in a way that’s both logical and dramatic.

Don’t get ensnared by the ruinous idea that structure is the enemy of originality and this thing we call “story.” In fact, the opposite is true.

So become a great chef. Know your ingredients. Cook up a delicious tale by mixing the familiar with your unique blend of spices.

Your readers will eat it up.

What is your view of originality? What are some examples from writers you admire?

Love your way of boiling down craft into easily-digestible bites, Jim.

“Human beings bring only a handful of facial features to the blueprint of how we look— two eyes, two eyebrows, a nose, a mouth, a pair of cheekbones, and two ears, all pasted onto a somewhat ovular-to-round face. That particular blueprint doesn’t often vary much, either. Interestingly enough, this is about the same number of essential storytelling parts and milestones that each and every story needs to showcase in order to be successful.

Where we humans are concerned, the miracle of originality resides in the Creator, who applies an engineering-driven process—eleven variables—to an artistic outcome. Where art is concerned, there is something to be learned from that.

We get to play God with our stories. And just like the Big Author in the Sky, we have a finite set of tools to work with, and an expectation, a format, as to how they are assembled. If nature can deliver billions upon billions of versions of an eleven-element blueprint with hardly any duplication, we storytellers shouldn’t begin to label this same level of story blueprinting as a formulaic undertaking.” — Larry Brooks, Story Engineering

Thanks for the quote from brother Brooks, Sue. We run along similar tracks!

As someone with a culinary background, I appreciate this post! And of course this applies to many art forms, not just writing.

Couple of laugh out loud phrases. “You don’t cook an omelete with a watermelon.” And then, “Of course, an author is free to write experimental fiction, which is also known by its unofficial name, Fiction That Doesn’t Sell.”

I’d like to borrow those for an upcoming NaNo kick-off event I’m hosting at the library next week. And I am delighted to attribute to Alice Water, you, and TKZ.

To try to answer one of your questions.

I admire the author and artist Austin Kleon whose tagline is “steal like an artist” or something along those lines. His approach, you don’t need to reinvent the wheel, hits the mark and aligns with your thoughts on originality. Kleon does something called blackout art. He takes a page from the newspaper and with a Sharpie, blacks out everything except the poem or his truth from the words already printed. Clever. And original.

That’s all I’ve got for now. Headed for the second cuppa. Happy Sunday.

Borrow away, Maureen, and thanks for chiming in.

Good morning, Jim.

I loved your analogy. When you quoted Bickham, I noticed his use of the word “architectural.” I have always thought that this discussion of plot and structure points to Architecture and construction as an obvious analogy, And, when you think about it, every art form has a basic “structure” that, of necessity, requires a “foundation” that is universal within that art form. I’ve yet to see a painting with the canvas plastered on top of the paint.

Sue’s comment above, and her quote from Larry Brook’s STORY ENGINEERING, reminded me that we have an advantage with the infinite number of possibilities we can “create.” The human DNA is built on a four base genetic code vs. a computer’s binary code. And if we’re not satisfied with those options, we can write fantasy or sci fi.

Thanks for another great teaching moment.

Right, Steve. Architecture is a great analogy. I use the suspension bridge to illustrate structure. It all goes back to giving readers an experience, something they are paying you for. And they experience story (and indeed, the world) through common “architectural” expectations. Let’s help them out!

To me, originality is a new twist on an old theme. Vampires aren’t new, but Charlaine Harris gave us a new view with her Southern Vampire series — she applied the conventions of a southern novel to a vampire story and it worked brilliantly.

Good point, Elaine. That’s originality on a macro level. We can also do it on a micro level, through characters who surprise us.

Good enough for Aristotle, good enough for me.

On originality, I heard John Mellencamp refer to it as stealing, copying aspects of other’s styles and adding your own voice to that mix, ergo originality, art.

Aristotle never sold a screenplay. What did he know?

I think fighting the idea of structure and form is holding on to the belief that ‘writing is fun’. For me, it isn’t an amusement. It’s hard. What is fun is completing a story and knowing it works. Even rereading a scene that works makes my heart sing. I’m working on a collection of short stories. Every one is different and every one started with the same structure. (I actually have the structure saved in Scrivener.)

One of my new favorite authors wrote the 60 some Doc Savage adventure books. His name is Lester Dent. He is a great believer in structure. This is a link to the short version of his formula. http://www.paper-dragon.com/1939/dent.html

That Lester Dent was a great pulp writer. So many of them understood all this, that they were providing a product for a customer, and respecting that customer!

Originality to me is hard to point out in a book that I want to look at as an example. And is our assumption that if a book sold well it showcased originality as an ingredient? It seems so elusive. Based on perception. And every reader’s perception stems from their own unique set of experiences.

Take The Hunger Games for example. I would suppose I thought it was original because it’s the only story I remember reading where a girl’s sister is chosen as the sacrifice and takes her place, but since that’s the only fiction of that category I’ve ever read, I don’t really know that for sure. And if it’s not that that makes the story original, what is? I don’t perceive the originality coming from a play with words–Ms. Collins spun the same sentences as we all do, but obviously to great effect given its phenomenal success.

My point is simply that when I study stories that have gone on before, it’s not necessarily easy to pick out these writing lessons by examining the work, because no 2 readers come from the same place. But it won’t stop me from examining. LOL!

Even the effort of examining pays dividends, BK.

The Hunger Games plot has been done before. Go back to the classic story “The Most Dangerous Game” (published 1924). The movies Rollerball and Death Race 2000, etc.

The originality came from the story world that encased the games, and of course the spice of the characters.

Excellent metaphor, Jim. I love to cook. I’m pretty good at it. But when I first started out cooking, I burned water. My husband still lovingly refers to one of my first “gourmet” attempts as “Hockey Puck Chicken.”

But I really wanted to learn to cook so I got some BASIC cookbooks. (Joy of Cooking and the Better Homes and Garden Cookbook…still have them both). I learned “the craft” of cooking, all the basic terms and techniques. Thirty years later, I can make a really good meal out of almost anything in the fridge and pantry, and on occasion I produce something inspired. 🙂 But the best part is now I have the courage to improvise and add my own touches to recipes. But no way could I have gotten to this point without mastering the basics. As one of my mentors Julia Child said, “Learn to cook so you’re not a slave to recipes.”

Oh…and use lots of butter. And never use cheap wine.

Perfect comment. Kris. All of it. Especially the part about the butter.

Good demonstration of originality with your creative metaphor. You got your usual points across in an enjoyable way.