Category Archives: Michael Connelly

The Three Rules for Writing a Novel

Books on the Installment Plan

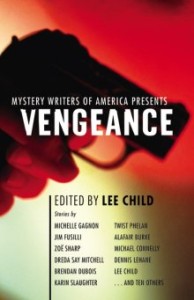

THE VENGEANCE ANTHOLOGY

I hope you’ll excuse a little BSP today. I have a short story out in the new Mystery Writers of America Anthology, VENGEANCE, edited by the wonderful Lee Child. Plus I think there’s a lesson to be learned from the long, occasionally tortu ous journey this story has had over the past twelve years…

ous journey this story has had over the past twelve years…

Some background first. This was the first real piece of crime fiction I ever wrote. I composed it while working with the San Francisco Writers’ Workshop back in 2000. I’ve never been much of a short story writer, but at the time I was just diving back into fiction, and figured that playing around with briefer pieces might help me find my voice. So this was one of the first (and only) stories I ever wrote. Shortly afterward, I started working on my first book (the one that never sold), and then, eventually, moved on to writing THE TUNNELS.

I always had a soft spot for this story, but had no idea what to do with it. Filled with hope, I submitted it to a few literary magazines. After it was roundly rejected by them, I shrugged and put it away in a drawer.

Fast forward to 2004. Lee Child was headlining the Book Passage Mystery Writers’ Conference, and at the last minute I scraped together enough money to attend. On the last night of the conference, all the participants were invited to read a short piece of fiction, kind of an informal critique exercise. I wasn’t happy with the opening of my novel yet, and was considering skipping the event entirely until I remembered this story. So I pulled it out of the drawer, dusted it off, and read it that night. All in all, it was well received; Lee attended the reading, and spoke with me afterward about how much he’d liked it. Which was terribly flattering, but again, I had no idea what to do with it. So back in the drawer it went.

Fast forward another seven years, to 2011. Lee emailed me out of the blue and asked if I’d ever done anything with that story from the Book Passage reading. He explained that he was putting together an anthology for the MWA centered around the theme of vigilante justice, and thought my piece might fit in perfectly. He asked if it would be all right to include it. Once I finished turning cartwheels across the room, I said yes.

So this week my little story, the first piece of crime fiction I ever wrote, was published alongside the work of some of my idols, including Lee, Dennis Lehane, Michael Connelly, Karin Slaughter, and Zoe Sharp. To say that I was honored to be part of this anthology would be a tremendous understatement. It really is a dream come true.

And from it, I’ve learned a few things:

a) It’s impossible to judge the true value of a writing conference. Sometimes they might seem like a waste of time and money, but you never know what may come of the contacts you make there.

b) Never empty that drawer. The story that can’t find a home today might bear fruit years down the road (or even decades!)

c) Never give up. I have to confess, when those literary magazines first snubbed my work, I was disheartened and almost tossed in the towel. I really thought the story was pretty great, and discovering that not everyone agreed was crushing. It was hard to go on when it felt like what I was writing might never be appreciated, or even read, by anyone outside my critique group. Eight published or soon-to-be-published novels (and one short story) later, I’m really happy that I decided to forge ahead.

What follows is an excerpt from my story, IT AIN’T RIGHT. The VENGEANCE Anthology is currently on sale at bookstores and online.

“It ain’t right, is all I’m saying.”

Joe just kept walking the way he always did, shovel over his shoulder, cigarette clinging to his bottom lip.

“You hear me?”

He stopped and turned, lifting his head inch by inch until his eyes found my hips then my breasts then my eyes. A dustdevil whirred away behind him, making the bottom branches of the tree dance like girls on Mayday, up and down. He stared at me long and hard, and I felt the last heat of the day seeping into my skin and down through my bones, reaching inside to meet the cold that burrowed in my stomach early that morning.

“She’s dead, ain’t she?” With his free hand he scratched his belly where the bottom of his ‘Joe’s Diner’ shirt had pulled away.

“Yeah, but just cause she’s dead don’t mean she should be put down like this.”

He looked past me, towards where the road met the hill and dove behind it, wheat tips glowing pink in the twilight. “What else we gonna do with her?”