NOTE: Because of the timely nature of this item, Jordan and I are switching slots this week. Her post will come on Sunday.

It’s been a rough week for fans of the book and film To Kill A Mockingbird.

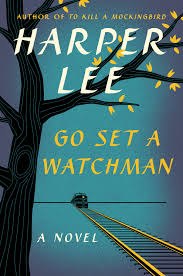

HarperCollins delivered the “new” Harper Lee novel, Go Set A Watchman. Many people  still harbor strong suspicions that the aging and infirm Ms. Lee was manipulated after fifty years of steadfastly refusing to publish anything else.

still harbor strong suspicions that the aging and infirm Ms. Lee was manipulated after fifty years of steadfastly refusing to publish anything else.

Be that as it may, it’s here. Strangely unedited (it renders a different version of the Tom Robinson trial, for example), the novel is primarily about one thing––a daughter’s coming to terms with her less-than-perfect father.

That’s the big shocker everyone is talking about: In Watchman, Atticus Finch is revealed to be a segregationist. He does not want the government or the courts telling him or his community how to live. He thinks the Supreme Court is using the Fourteenth Amendment to erase the Tenth Amendment. And he believes the black population is not ready for the responsibilities of citizenship.

In Watchman, Atticus is a member of the Citizens’ Council of Maycomb County, a group of white men strategizing on how to deal with Brown v. Board of Education, and the incursion of the NAACP and northern progressives into the South.

Harper Lee with her father, Amasa Coleman Lee

The grown-up Jean Louise Finch (Scout from Mockingbird) discovers this about the father she idolized as a child. It all leads to the climactic scene––a knockdown argument between Jean Louise and Atticus over the “negroes” (the term the book uses).

“Let’s look at it this way,” Atticus says. “You realize that our Negro population is backward, don’t you? You will concede that? You realize the full implications of the word ‘backward’, don’t you?”

Jean Louise is horrified and responds: “You are a coward as well as a snob and a tyrant, Atticus.” She goes on to compare him to Hitler (!) and admittedly tries to grind him into the ground.

As a historical document, written in the mid-1950s, Watchman is reflective of so many similar confrontations that took place back then––college-educated white children coming home to challenge their parents’ views on race, especially in the South.

I will not reveal what happens in the last chapter. Suffice to say I was simultaneously moved and unsatisfied by it. Which may be the very point Harper Lee, the author, intended to make.

We live in an imperfect world, loving imperfect people.

Which brings us back to Atticus Finch. He was always seen as a virtual saint, especially as played by Gregory Peck in the movie.

But what everyone seems to miss is that Atticus held the same segregationist views in Mockingbird.

I’ve taught Mockingbird in seminars, most notably the Story Masters sessions I do with Donald Maass and Christopher Vogler. We go through the book chapter by chapter, talking about technique and style.

There is a single, enigmatic passage in the book that’s always troubled me. I never knew quite what to do with it. Until now, with the publication of Watchman.

It comes early in Chapter 15, the very chapter where Atticus sets himself in front of the lynch mob at the jail. The narrator, Scout, reflects on how Atticus would sometimes ask, “Do you really think so?” as a way to get people to think more deeply.

That was Atticus’s dangerous question. “Do you really think you want to move there, Scout?” Bam, bam, bam and the checkerboard was swept clean of my men. “Do you really think that, son? Then read this.” Jem would struggle the rest of an evening through the speeches of Henry W. Grady.

So what was Jem’s opinion? Who was Henry W. Grady? Why would Atticus give his boy a book of Grady’s speeches?

In light of what I’m about to reveal, I think Jem (who is the more sensitive of the children) probably said something along these lines: “Atticus, it’s just not fair that colored kids don’t get to go to school with white kids.”

Atticus gives him the Grady speeches, which are available online.

Henry W. Grady (1850-1889) was a post-Civil War advocate of what he called the “New South.”

The old South rested everything on slavery and agriculture, unconscious that these could neither give nor maintain healthy growth. The new South presents a perfect democracy, the oligarchs leading in the popular movement; a social system compact and closely knitted, less splendid on the surface, but stronger at the core; a hundred farms for every plantation, fifty homes for every palace; and a diversified industry that meets the complex needs of this complex age.

The new South is enamored of her new work. Her soul is stirred with the breath of a new life.

But what about the population of emancipated slaves? What of their future? Grady said things like this:

What is this negro vote? In every Southern State it is considerable, and I fear it is increasing. It is alien, being separated by radical differences that are deep and permanent. It is ignorant — easily deluded or betrayed. It is impulsive — lashed by a word into violence. It is purchasable, having the incentive of poverty and cupidity, and the restraint of neither pride nor conviction. It can never be merged through logical or orderly currents into either of two parties, if two should present themselves. We cannot be rid of it. There it is, a vast mass of impulsive, ignorant, and purchasable votes. With no factions between which to swing it has no play or dislocation; but thrown from one faction to another it is the loosed cannon on the storm-tossed ship.

These, then, were the views Atticus was passing along to Jem in Mockingbird, and holding onto in Watchman.

In other words, Atticus Finch was never a perfect saint.

But let me ask you this: who among us is? I’ve not known very many in my lifetime.

Which means this complex Atticus Finch is a more realistic character than the “perfect” one. He is still the man who defended Tom Robinson to the best of his ability. But he also holds odious, segregationist views. Jean Louise (and Harper Lee) make clear how wrong that is.

So what do we do with such a man, or woman, or family member? What are the limits of love? What is the cost of growing up? Are we compelled to hate those who hold views we cannot abide?

That’s what Harper Lee is asking in Go Set A Watchman.

The novel does not destroy the Atticus Finch of Mockingbird. Rather, it renders him flawed and therefore human.

You know, like the rest of us.

Jesus taught people to hate the sin, but love the sinner. In a world of so much hate, this message is exactly what we need to hear. Harper Lee’s novel, so long locked up in a safety deposit box, may therefore be more important than we think.