I’ve joined the electronic revolution and purchased an iPhone. Having been resistant for some time, I could no longer avoid the temptation of having the social networks at my fingertips, cool apps to explore, email at the tap of a button, and a personal calendar on hand. Now I can relieve my purse of my pocket-sized appointment book and my emergency Sudoku pad. No longer will I have to fumble for someone’s phone number or wish I could send a photo directly to Facebook. I can do all of these things and more.

And therein rests the problem. The iPhone, like its larger cousin the iPad, is in itself a complete source of entertainment. Miss a favorite TV show? Watch it on your device. Need to look up the nearest pizza palace? Ask Siri. Need to kill time at the doctor’s office? Read a book on iBooks. Or better yet, play a game of Solitaire.

No wonder people’s attention spans are decreasing. It makes me worry for the future of reading. Who will be able to concentrate on finishing an entire novel when so many other activities require less effort?

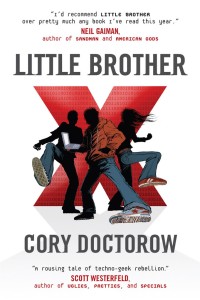

Thank goodness for teen fiction that captures the interest of our youth and perhaps spurs them on to develop a lifelong reading habit. Because once the older generation who gobbles up our stories in print form dies off, who will be left? Consumers who expect their reading material to arrive in the form of daily excerpts? Will the art of storytelling devolve into single page entries? How can we make reading more attractive to the younger set to compete with iTunes?

Storytelling will always be part of our psyche even if the means of delivery evolves. But as a novelist, I am concerned for the future of our art. Can those of us trained to write lengthy works adapt to the changing marketplace? What if we have no choice? Do we want to write shorter, compelling, quicker prose? Can we compete with smartphones and tablets, or must we join the revolution and change our techniques to suit them?