I once had a rose named after me and I was very flattered. But I was not pleased to read the description in the catalogue: no good in a bed, but fine up against a wall. — Eleanor Roosevelt

By PJ Parrish

Of all the things writers have to worry about, you wouldn’t think description would be at the top of the list. Yet I can’t tell you how many times this has come up in all the workshops I’ve done over the decades. The questions!

How much description do I need? How should I describe my main charcter? Did I spent too much time describing the haunted mansion? Should I describe the weather? Speaking of weather, Elmore Leonard doesn’t have description. Why can’t I just leave it out like he does?

As someone who loves to describe stuff, I think of description is just one potent ingredient that goes into the alchemy of a great book. But “potent” is the operative word here. Too little and you’re missing a chance to emotionally connect with readers. Too much and you’re risking them skipping over your hard-wrought pages.

Where’s the sweet spot?

Some writers are renowned for revelling in description.

“Then the sun broke above the crest of the hills and the entire countryside looked soaked in blood, the arroyos deep in shadow, the cones of dead volcanoes stark and biscuit-colored against the sky. I could smell pinion trees, wet sage, woodsmoke, cattle in the pastures, and creek water that had melted from snow. I could smell the way the country probably was when it was only a dream in the mind of God.” ― James Lee Burke, Jesus Out to Sea

Some writers opt for none. I had to leaf through five of my Elmore paperbacks until I found something that came close to description. From Mr. Paradise.

They’d made their entrance, the early after-work crowd still looking, speculating, something they did each time the two came in. Not showgirls. More like fashion models: designer casual wool coats, oddball pins, scarves, big leather belts, definitely not bimbos. They could be sisters, tall, the same type, the same nose jobs, both remembered as blonds, their hair cropped short. Today they wore hats, each a knit cloche down on her eyes, and sunglasses. It was April in Detroit, snow predicted.

In his dedication for Freaky Deaky Leonard thanked his wife for giving him “a certain look when I write too many words.” And we all have memorized nos. 8 and 9 from his (in)famous Ten Rules For Writing:

- Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

- Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

I can almost hear some of you out there mumbling, “Okay, but this doesn’t help me. What do I describe and how much do I need?” I’ll try to help. But let’s have some fun first. Quiz time! Can you name the characters being described in these famous novels? Answers at end.

- He was dark of face, swarthy as a pirate, and his eyes were as bold and black as any pirate’s appraising a galleon to be scuttled or a maiden to be ravished. There was a cool recklessness in his face and a cynical humor in his mouth as he smiled.

- [His] jaw was long and bony, his chin a jutting v under the more flexible v of his mouth. His nostrils curved back to make another, smaller, v. His yellow-grey eyes were horizontal. The v motif was picked up again by thickish brows rising outward from twin creases above a hooked nose, and his pale brown hair grew down–from high flat temples–in a point on his forehead. He looked rather pleasantly like a blond satan.

- He was a funny-looking child who became a funny-looking youth — tall and weak, and shaped like a bottle of Coca-Cola.

- It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced — or seemed to face — the whole external world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just so far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself, and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey. Precisely at that point it vanished — and I was looking at an elegant young rough-neck, a year or two over thirty, whose elaborate formality of speech just missed being absurd. Some time before he introduced himself I’d got a strong impression that he was picking his words with care.

- Her skin glistening in the neon light coming from the paved court through the slits in the blind, her soot-black lashes matted, her grave gray eyes more vacant than ever.

- [He] was utterly white and smooth, as if he were sculpted from bleached bone, and his face was as seemingly inanimate as a statue, except for two brilliant green eyes that looked down at the boy intently like flames in a skull.

- [He] had a thin face, knobbly knees, black hair, and bright green eyes. He wore round glasses held together with a lot of Scotch tape because of all the times Dudley had punched him on the nose.

Back to work. First of all, I come down on the pro side of description. As I said, it is one of the potent tools in your craft box. When done well, it creates atmosphere and mood, sets a scene, and gives your reader a context to the world you are asking them to enter. It also helps your readers emotionally bond with your characters, having them see, feel, hear and smell the story.

But I get why so many writers, especially beginners, get frustrated with description. Dialogue — good and bad — sort of spools itself out. Action scenes have a certain momentum that keeps the writerly juices flowing. But when you have to pause and face that blank page and come up with describing the scene or person in your head — well, it’s like trying to speak a foreign language. It get that. I really do.

Here’s the thing I have learned: Only describe the stuff that is necessary for readers to understand and connect to your story. Example: Your character walks into a room. If UNDERSTANDING THE ROOM SENSORILY adds to your story, then yes, you have to describe it. If not, don’t. Consider this example:

John opened the door and walked into the room. The smell hit him — decaying flesh but with a weird undernote of…what was that? Pine trees? The pale December light seeped around the edges of yellowed window shades and at first he couldn’t make out anything. Then details swam into focus — an old coiled bed frame heaped with dirty blankets. And suspended above the bed, hundreds of slips of paper. No, not just paper. Little paper Christmas trees. No, not…then he recognized the pine smell. It was coming from the air fresheners, those things people hung on their rearview mirrors. The heap of blankets on the bed…he moved closer. It was a body. Or what was left of one.

I made that up, basing it on a scene from the movie Seven where cops Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman discover a corpse. Love this movie…

Writing this scene in a thriller, of course you have to describe it. You filter it through the characters’ senses so the reader can experience the horror.

Now, if Brad and Morgan were just walking into any room, that had no SENSORY bearing on your plot, you’d write:

They entered the room. Bare bones furniture overlaid with dust. A quick scan told them it was empty, no sign anyone had lived in the place for a long time. Another dead end.

See the difference? Describe, but only when it makes a difference.

So where is your sweet spot? I can’t answer that. Like any skill, it’s something you have to practice, play with, and fine tune. It also is part of your style. Your way of describing things should be singular to you. You can watch that scene from Seven and your way of describing it should be completely different than mine.

One last point before we go. The biggest mistake writers make when describing is being overly reliant on sight. Be aware, when you the writer enter a scene, that you do it with sensory logic. Always consider the sequence of the senses. Smell is often the first thing you notice. Sound might be the primary thing triggered. Sight is rarely the first sense to connect.

One more quick example from one of my favorite authors. I love how Joyce Carol Oates uses smell to open her description of the one-room schoolhouse she attended as a child in rural New York:

Inside, the school smelled smartly of varnish and wood smoke from the potbellied stove. On gloomy days, not unknown in upstate New York in this region south of Lake Ontario and east of Lake Erie, the windows emitted a vague, gauzy light, not much reinforced by ceiling lights. We squinted at the blackboard, that seemed far away since it was on a small platform, where Mrs. Dietz’s desk was also positioned, at the front, left of the room. We sat in rows of seats, smallest at the front, largest at the rear, attached at their bases by metal runners, like a toboggan; the wood of these desks seemed beautiful to me, smooth and of the red-burnished hue of horse chestnuts. The floor was bare wooden planks. An American flag hung limply at the far left of the blackboard and above the blackboard, running across the front of the room, designed to draw our eyes to it avidly, worshipfully, were paper squares showing that beautifully shaped script known as Parker Penmanship.

So, Oates is leading the reader into the room. Note the PROGRESSION of senses: First, you smell varnish and wood smoke. Next, you become aware of the quality of the light — gauzy from the windows and ceiling lights. Only then does Oates move to sight, and even then we have to squint to bring the scene into focus. Take note, too, of the small telling details she uses that make us build an image-painting of this room in our imaginations — desks in a row like a toboggan, old wood like horse chestnuts, and the one I love because I can remember it — paper squares of perfect Parker Penmanship.

Answers to quiz:

- Rhett Butler Gone With The Wind

- Sam Spade The Maltese Falcon

- Billy Pilgrim, Slaughterhouse Five

- Jay Gatsby The Great Gatsby

- Lestat Interview With The Vampire

- Harry Potter. The Sorcerer’s Stone.

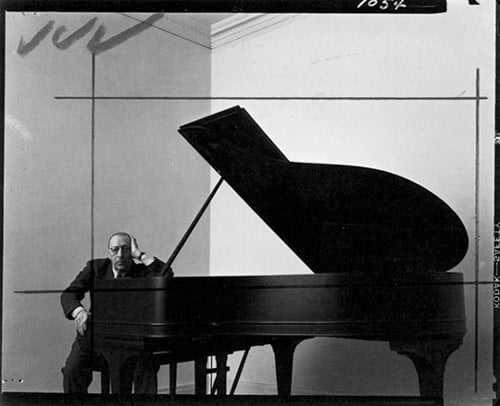

The other day, I saw a Facebook post from my friend Joseph Finder. I like Joe a lot. We’ve been on panels together. He writes good books that sell really well. He’s a really nice guy. But this photo at left that he posted the other day made me want to…heck, I don’t know what. This is Joe’s writing office. It’s perfect. How would someone NOT get inspired sitting in a place like that? Why can’t I have a writing house like that? Maybe I’ll go up to Cape Cod and TP his…

The other day, I saw a Facebook post from my friend Joseph Finder. I like Joe a lot. We’ve been on panels together. He writes good books that sell really well. He’s a really nice guy. But this photo at left that he posted the other day made me want to…heck, I don’t know what. This is Joe’s writing office. It’s perfect. How would someone NOT get inspired sitting in a place like that? Why can’t I have a writing house like that? Maybe I’ll go up to Cape Cod and TP his…