Dear Readers: I am still in Italy and out of touch. Our Wifi here is almost non-existent! So I hope you don’t mind a re-post. This is one of my favorites. See you soon. — PJ

Paragraphing is a way of dramatization, as the look of a poem on a page is dramatic; where to break lines, where to end sentences. — Joyce Carol Oates.

By PJ Parrish

Yesterday, Sue posted her critique of a First Page submission. On first read, I thought it was pretty good but something about it was bugging me. Then I just looked at it instead of reading it. It hit me that the paragraphing wasn’t quite right.

Paragraphing? Who cares about paragraphing? You just hit enter when it feels right, right? Nope. Proper paragraphing is one of the most underrated tools in your writer’s box. So allow me to wander into the weeds today and talk a little inside baseball. (I worked hard on that mixed metaphor, by the way)

Two main problems with the submission yesterday: The writer had made the common mistake of burying thoughts and dialogue within narrative.

Second problem: All the paragraphs are about the same length. Why is that a problem? Because it goes to pacing and rhythm. No variation in paragraphs is boring to the eye and that translates to boring for the reader’s imagination. But if you learn to master the fine but subtle art of judicious paragraphing, you can inject interest and even tension into your story.

Let’s address problem one first. This opening paragraph is essentially narrative. But inserted within that is both dialogue and thoughts. Here’s the paragraph:

Arizona Powers slammed her palm into the office wall, ignoring the stinging sensation. Unbelievable. “Are you kidding me? I’m not doing that. I’m a federal agent, not a babysitter.” Her boss had clearly lost his mind. She spun on her hiking shoe, locking eyes with Senior Special Agent Matt Updike. Her fingers fidgeted with a button on her shirt. I deserve a second chance.

Dialogue and thoughts are ACTION. They deserve to be lifted out of narrative and given lines of their own so the reader can emotionally latch onto them, and by extension, your character. This opening paragraph would be more effective (and more interesting to the eye) if it were deconstructed with better paragraphing:

Arizona Powers slammed her palm into the office wall, ignoring the stinging sensation, and stared hard at her boss.

“Are you kidding me? I’m not doing that. I’m a federal agent, not a babysitter.”

Matt Updike shoved his chair backward, rose and closed the distance between them in two strides.

“I’m not kidding. You are doing this,” he said. “You don’t have a choice.”

She could smell his stale coffee breath and see a vein bulging in his neck, but she resisted the urge to step back. Her boss had clearly lost his mind. But she wasn’t going to take this. She deserved a second chance.

See the difference? The drama of the scene is enhanced by allowing the thoughts and dialogue to stand out — all by simple paragraphing. Here’s something interesting: The rewrite is LONGER but it reads FASTER. Why? Because the reader doesn’t need to ferret out the important thoughts and dialogue. It’s your job, as the writer, to mine out the nuggets for them.

Now let’s consider the basic question of length of paragraphs and how that affects your reader. How long should your paragraphs be? Sounds like a dumb question, but it’s not. You need to consider it deeply.

Let me re-quote this from Ronald Tobias’s The Elements of Fiction Writing: Theme & Strategy,

The rhythm of action and character is controlled by the rhythm of your sentences. You can alter mood, increase or decrease tension, and pace the action by the number of words you put in a sentence. And because sentences create patterns, the cumulative effect of your sentences has a larger overall effect on the work itself. Short sentences are more dramatic; long sentences are calmer by nature and tend to be more explanatory or descriptive. If your writing a tense scene and use long sentences [me here: or long paragraphs], you may be working against yourself.

I often liken writing to music. Composers use punctuation to speed up or slow down pace and musicians use types of “articulation” to enhance whatever mood they are going for — intense? dangerous? romantic? thoughtful?

Good writers use similar tools — punctuation, length of sentences and paragraphs (short and choppy or longer and measured?) to create an emotional response in their readers. The best writers understand this not only creates emotion, it provides variety on each page and over the whole book.

Pacing is not just aural, it’s visual. How your writing LOOKS on the page is important. Which brings us back to the paragraph. How many you use per page, and how long or short your paragraphs are should be conscious choices you make. Here is the same thought, expressed two different ways:

Fragments, the length of sentences, punctuation, and how often you paragraph can all work to give a particular pace. If you really think about, you’ll realize that you can use sentence and paragraph structure to create a feeling of speed or slowness, depending on what kind of emotional response you want to induce in your reader.

Okay, that gets my point across, right? But what if I structured the same thought this way:

Think of it! You can move a reader through a story fast. Their hearts will race!

Or you can slow them down and make them use their heads.

It’s all in how your sentences look on the page.

The first is measured, more academic in pace, meant to make you slow down and digest the thought. The second is lively and urgent, making you anticipate an important climax-point. Neither is correct. They are just two different styles of pacing, word choice, sentence length and paragraphing to different affect.

I think most of us here, being in the crime business, know we shouldn’t write a lot of long paragraphs. You can get away with some, especially in description. But these days, too many long paragraphs per page looks “old-fashioned” or worse, “textbook.” It worked for Dickens and even for a stylist like Delillo. Not so much for the rest of us today.

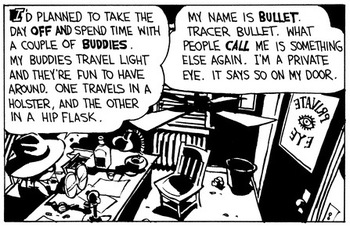

Are any of you out there art folks or designers? Then you understand the value of “white space” or “negative space.” Simply put, negative space is the area around and between a subject. It appears in all drawings, paintings and photographs. The “subject” below is enhanced by the negative space surroudning him. (Notice, too, the crop lines that make for an even more compelling negative/positive composition!)

Paragraphing provides white space. Don’t believe me? Go read Elmore Leonard.

Ray Bradbury said that each paragraph is a mini-scene and when you hit ENTER you are helping your reader enter a new scene, thought or action. I’ll leave you with one more example. It’s from one of my favorite opening pages from a novel.

It was a pleasure to burn.

It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon-winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning.

Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame.

That’s the opening to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. I love the way the first line sits there all alone, like a roadside sign that you’re entering hell. Then he gives us this amazing loooong graph with gorgeous imagery and the nonchalance of the unnamed man. And then, a third paragraph — BAM! — he gives us our arsonist-star by name.

Bradbury could have made this all one graph. But no, he chose three. Your turn. Choose wisely when to hit enter.