By PJ Parrish

Well, I’m back. Sorry I missed my slot last time around, but I had to bury another laptop. My Microsoft Surface gave me The White Screen of Death. After a mild panic (I am bad about backing up) I bundled it off to my geek. He looked at the white screen and said, “Huh. Never seen that before.” You don’t want to hear those words from your dentist, your geek, or your lover the first time you’re doing it. Anywho, he got all my data and taught me how to retrieve it from the cloud-thingie. So, I just want to give you some advice, if you are computer-stupid like me: BACK UP YOUR DATA. There are a million good programs out there that do this.

Now back to our regular programming. Here’s a First Page Submission in what the writer calls “mystery crime fiction.” Give it a read and let’s talk.

Death at the Tenderloin

Another senseless murder was by no means unfamiliar to me.

As a San Francisco cop, I’ve seen cruelty to humanity for over a decade. As a seasoned detective, I’m desensitized—It’s just another death in the city.

The victim was a middle-aged man with a fair complexion and wavy graying black hair. He was average height, somewhat thin, and wearing what appeared to be an old worn-out pilot’s uniform with yellow stripes on his button-up jacket sleeves. He was found behind the Black Bunny Bar sitting, and arms crossed on his lap, legs splayed out straight, leaning against a dumpster as if taking a nap before hopping into the cockpit. If it were not for the apparent blunt-force trauma to his skull, a passerby could easily tag him as a homeless drunk.

Four yellow stripes unquestionably a captain, I thought.

The uniform sparked memories. I joined the U.S. Air Force Academy and graduated from the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit program. The positives were two-fold. One, I became an elite of the elites. Second, it distanced me from a San Francisco street detective who ruled with an undeniable force on the street and at home—a retired vet who expected the utmost discipline from his only son. Instead of improving our father-and-son relationship, my triumphs worsened it. I was living in Quantico, Virginia, when my father succumbed to cancer, and three months later, I laid him to rest. Precious time had passed between us—an act I later questioned.

I looked at my partner, Brynn, to see her reaction to this atypical scene.

“What do you see?” I asked as I put on my floater mask to filter out the foul odors of decomposition.

Brynn was kneeling beside the body, her cracked lips slightly open. She lifted her palm in a give-me-a-moment gesture, perhaps trying to digest the gruesome scene.

You’ve seen nothing yet, I thought.

Brynn O’Reilly is a petite woman at 120 pounds. She is of Irish-American heritage with long ash-brown hair. She favors a black blazer as the Unit uniform, complemented with flared-bottom jeans and sage color boots to match her eyes. Only two years as a street cop and six months at the Major Crimes Unit, Brynn is known as a pit bull investigator. Her quick rise through the ranks came compliments from her family lineage, namely her father and grandfather, the current and retired chief of police. Nevertheless, she is a good detective with keen instincts and a thirst for sleuthing—from dissecting blogs to graffiti on public restroom stalls. Everyone leaves a footprint of clues is her modus operandi.

_____________________

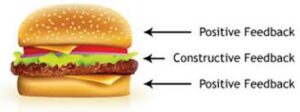

Okay, let’s start with some obvious stuff. You have one chance to make a good first impression and hook your reader, There are four things you always want to avoid in your opening pages:

Don’t Be Boring. Whatever your opening dramatic moment is, don’t choose something that’s been done to death. Don’t open with a bad dream. Don’t open with your cop getting a phone call in the middle of the night. Don’t open with the protag navel-gazing. (ie thinking, musing, remembering, regretting the past).

This submission? Borderline. If you are opening with a cop checking out a dead body, you really have to work hard to make it feel fresh. Although I like one thing about the crime scene, other problems diminish it, for reasons outlined below.

Avoid the dreaded info-dump. Don’t bore your reader with information about the protag’s past in the early pages. Capture their imagination with a compelling character and an intriguing situation. Background info can be woven in later.

This submission: Two chunky paragraphs of backstory inserted too early before the dramatic opening scene has a chance to gel.

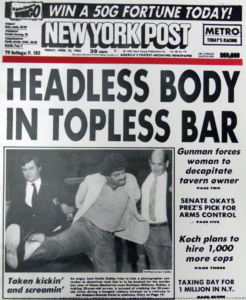

Steer clear of cliches. Crime fiction is fertile ground for this, and nothing will turn an editor off more quickly than stale Wonder Bread. Tropes that need to die: crusty vet cop teamed up with rookie (usually female). Vet cop whose wife or kid died so he’s drowning himself in booze. Crabby old boss chewing out rogue cop (Dirty Harry was there first). Vet cop with bitter ex-wife who tells him “you’ll never see your kid again.” The psycho sidekick who does the dirty deeds the hero won’t do. We could go on.

This submission? Old cop paired with relatively inexperienced female.

And last but most important: Don’t tell when you can show. I’ve written several blogs on this subject because it’s so important yet so difficult to explain well. If you have problems with this, go back into the TZK archives. Lots of good advice there.

This submission? This is its basic problem. This opening is not badly written. It just relies too heavily on telling rather than showing.

What was the one thing that made me want to read on? The dead guy.

An apparent homeless man is found propped in an alley with his head bashed in. Nothing really interesting there. But the writer uses A TELLING DETAIL (not to be confused with show not tell). The air force uniform — especially the captain’s stripes — is the best thing in this submission. It grabbed my interest in a way the protag did not.

But here’s the caveat: We see the victim not through an immediate and well-crafted scene of SHOWING via the protag’s sensory “camera.” We get the victim info book-ended by the protag’s backstory. We get lots of thoughts from the protag — about his state of mind (“desensitized”), about his education (air force academy), about his success at the FBI (he’s “elite”), about his father (estranged and dead from cancer), and waaaay too much details on his partner, right down to her weight.

What we DON’T get is a clear picture of the crime scene and a reason to care enough to turn the page. We are TOLD we are in an alley in San Francisco. But we can’t see it because there are no details, no description. We are TOLD the murder is “senseless” but there is no hard evidence of that yet. I normally don’t like to rewrite someone else’s material, but I want to make a point. What if we got out of the protag’s thoughts and started right with what the “camera” of his consciousness can show us?

The dead man was propped up against the Dumpster behind the Black Bunny Bar, legs splayed out, head bowed on his chest. He could have been a homeless guy sleeping off a drunk. Except for the black oozing crack in his head. And the uniform he was wearing.

It was black, the dress shirt drenched dark blue in the heavy rain. For a moment, I thought he was one of ours. Then I noticed the four yellow stripes on his left sleeve.

I recognized those stripes. My father was wearing that same uniform the day I buried him ten years ago. The dead man wasn’t a San Francisco cop. He was air force. A captain.

“You want a closer look, Jackson?”

I looked over at my partner Brynn O’Reilly. Even in dim light of the alley, I could see the eagerness in her eyes. But she was waiting for me to move first. I didn’t want to. This was the fourth homicide I had been called to in the last month here in the Tenderloin. But that wasn’t what was holding me back.

The point I am trying to make here is that it is always more powerful to SHOW your scene and your character’s reaction via action and dialogue rather than TELL the reader what is happening via thoughts. It’s okay to drop a HINT of backstory. That’s often intriguing and starts setting up your character layering. But never waste precious moments in the first pages with long backstory and always try to make it relate to what is happening in present time.

Okay, let’s do a quick line edit. My comments in blue

Another senseless murder was by no means unfamiliar to me. “Senseless murder” is a media-created cliche. The idea of “senseless” refers to homicides that lack an objective external motivation. There is no way the detective here can yet determine this. Also, it’s just not an interesting opening line. And it’s TELLING. If the cop does indeed think it is “senseless” SHOW us this via his action or dialogue.

As a San Francisco cop, more telling. His actions SHOW us he’s a cop. And find a more graceful way to SHOW us where we are geographically. I’ve seen cruelty to humanity for over a decade. As a seasoned detective, I’m desensitized—It’s just another death in the city. You are TELLING us his state of mind. SHOW it via action and dialogue.

The victim was a middle-aged man with a fair complexion and wavy graying black hair. He was average height, somewhat thin, and wearing what appeared to be an old worn-out pilot’s uniform with yellow stripes on his button-up jacket sleeves. He was found behind the Black Bunny Bar sitting, and arms crossed on his lap, legs splayed out straight, leaning against a dumpster as if taking a nap before hopping into the cockpit. If it were not for the apparent blunt-force trauma to his skull, a passerby could easily tag him as a homeless drunk. Seeing a murder victim is a visceral thing, even for a vet cop. Way too much extraneous description. Hone in on the telling detail quickly.

Four yellow stripes. unquestionably A captain, I thought. Most interesting line in the opening. And you don’t need “I thought.” You’re in first person POV.

The uniform sparked memories.Don’t tell us. Go right into a memory. But man, keep it brief as possible! All the rest of this is numbing backstory. Yes, it is important to establishing your protag’s character, but find ways to weave this in later as the action dictates. This really brings your plot to a halt. I joined the U.S. Air Force Academy and graduated from the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit program. The positives were two-fold. One, I became an elite of the elites. Second, it distanced me from a San Francisco street detective who ruled with an undeniable force on the street and at home—a retired vet who expected the utmost discipline from his only son. Instead of improving our father-and-son relationship, my triumphs worsened it. More telling…I was living in Quantico, Virginia, when my father succumbed to cancer, and three months later, I laid him to rest. Precious time had passed between us—an act I later questioned. Conflict with a father figure is always interesting but this is, again, telling us.

I looked at my partner, Brynn, to see her reaction to this atypical scene. Nothing is atypical except that uniform. Exploit this more!

“What do you see?” I asked as I put on my floater mask to filter out the foul odors of decomposition. You didn’t mention he was in decomp mode above. Depending on the weather, it might not be there yet. Get your forensics in order. 24-72 hours postmortem: internal organs begin to decompose due to cell death; the body begins to give off harsh odors; rigor mortis subsides. 3-5 days postmortem: as organs continue to decompose, bodily fluids leak from orifices; the skin turns a greenish color. So make your protag look smart. Have him zero in on the state of the body and SAY SOMETHING INTERESTING to his partner. He’s experinced enough to be able to estimate time of death. Right now, your protag isn’t very active. He’s reactive and passive. Start making him a hero.

Brynn was kneeling beside the body, her cracked lips slightly open. She lifted her palm in a give-me-a-moment gesture, perhaps trying to digest the gruesome scene. Perhaps? Again, make him look smart. Here is where you can insert something about her background.

I knew O’Reilly had been in homicide here less than three months. Before that, she had two years in as a street cop down in Altherton. Riding a nice safe alpha unit, answering false alarms. Not much chance to see dead bodies there.

You’ve seen nothing yet, I thought. Not sure what this means.

Brynn O’Reilly is a petite woman at 120 pounds. She is of Irish-American heritage with long ash-brown hair. She favors a black blazer as the Unit uniform, complemented with flared-bottom jeans and sage color boots to match her eyes. Only two years as a street cop and six months at the Major Crimes Unit, Brynn is known as a pit bull investigator. Her quick rise through the ranks came compliments from her family lineage, namely her father and grandfather, the current and retired chief of police. Nevertheless, she is a good detective with keen instincts and a thirst for sleuthing—from dissecting blogs to graffiti on public restroom stalls. Everyone leaves a footprint of clues is her modus operandi. Again, everything is TELLING. “Pit bull investigator” is a TELLING cliche. SHOW us that she’s tough. He TELLS us she’s good, has keen instincts and a “thirst for sleuthing.” (no cop talks like that, that’s you the writer talking). “Everyone leaves a footprint of clues” is kind of interesting, although it’s pretty standard thinking and this protag is supposedly FBI trained? If you want to use it, SHOW us via dialogue. Which you don’t have enough of in these pages, by the way. DIALOGUE IS ACTION.

“What do you see, O’Reilly?” I asked.

“Blunt force trauma. Maybe with an ax-like instrument.”

“The body was moved afterward. Somebody took the time to prop him up like that.”

She looked up at me then scanned the garbage littered aspalt. “Everyone leaves a footprint,” she said.

So, forgive me, dear writer, for rewriting your opening some. I only wanted to make a point about how you can turn telling into showing. You’ve got some good stuff here. But find ways to make your protag (what’s his name, BTW?) do less thinking and more action. He’s coming off as an extra in his own movie.

A quick summary. Here are the pitfalls of TELLING

- Narrating the physical movements without being in character’s head.

- Use of too many ‘ly’ words in action or in dialog (i.e. She said impatiently, walked slowly, yelled angrily.)

- Use of stock descriptions, purple prose or lengthy descriptions of places (and people) especially those that have no bearing on the plot.

- Too many adjectives and cliches.

- Omniscient POV (distancing, describing from an all-seeing POV) A man getting hit on the head and pushed out a window would not notice “glittering shards of glass” as he falls six stories to the ground.)

Here are some strengths of SHOWING.

- Action that uses the senses, stays within the character’s consciousness and uses words and phrases that reinforce the mood of the scene.

- Strong verbs. (walked vs jogged, ran vs raced, shut the door vs slammed the door.)

- Original images and vivid descriptions that are filtered through the character’s senses in the present.

- One compelling adjective vs. a string of mediocre ones.

- Keep POV firmly in character’s head. (Establishes sympathy and connects emotionally.)

Think of this way. I just got back from Italy. Do you want to listen to me describe it? Or would you rather go see it, smell it, taste it for yourself? Yeah, I thought so. Make your reader feel like they are there.