Who is the most famous person you ever met? What were the circumstances?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I love my home town (although the relationship is strained these days). I love classic film noir shot on location in the City of Angels. A lot of detectives went in and out of City Hall, where the department was headquartered until 1955. Edmund O’Brien stormed into the homicide division in the famous opening tracking shot of D.O.A. (1949). “I want to report a murder,” he said. “Who was murdered?” they ask. “I was,” he says…and off we go.

I love my home town (although the relationship is strained these days). I love classic film noir shot on location in the City of Angels. A lot of detectives went in and out of City Hall, where the department was headquartered until 1955. Edmund O’Brien stormed into the homicide division in the famous opening tracking shot of D.O.A. (1949). “I want to report a murder,” he said. “Who was murdered?” they ask. “I was,” he says…and off we go.

The only movie in recent memory to capture the look and feel of 50s L.A. is L.A. Confidential (1997), directed by Curtis Hanson from the novel by James Ellroy. The sunny climes and palm trees during the day are juxtaposed against the corruption and vice of night. Good cops and bad cops. And some who are a little of both.

The film garnered critical praise and was Oscar nominated for Picture, Director, Screenplay, and Cinematography. Kim Basinger took home the statuette for Best Supporting Actress.

The film garnered critical praise and was Oscar nominated for Picture, Director, Screenplay, and Cinematography. Kim Basinger took home the statuette for Best Supporting Actress.

The plot centers around a mass slaying at a diner called The Nite Owl. The movie is a lesson in how to handle shifting POV as we follow the case through the eyes of three Lead characters.

Bud White (Russell Crowe) is known for violent, sometimes out-of-control behavior. But his rage is in the service of his sense of justice. He’s driven by a compulsion to save vulnerable women from abuse. (There’s a backstory reason for this that is revealed in Act 2).

The movie opens with an off-duty Bud White watching a home where a man is beating his wife. Bud pulls down the Christmas lights on the house, the man comes out and tries to clock Bud. Bud beats him up and handcuffs him to the stair railing. He gives the wife some cash and makes sure she has a place to go.

Thus we are drawn to Bud’s motive, but a little unsure about his methods.

This cross-current of emotion is a key to our wanting to watch Bud’s story. He’s not all good. He has a flaw which could be his undoing. This emotion intensifies in Act 2, when he is given a secret duty by his captain—beating up out-of-town mobsters trying to move in on L.A. territory. Here Bud is no longer a cop; he’s a thug, albeit on the “right” side.

Lesson: Memorable heroes should have strength, but also a flaw that could become fatal. That makes us interested to know which side will prevail.

Edmund Exley (Guy Pearce) is the opposite of Bud. Slender, thoughtful, smart, political. He goes “by the book,” which does not endear him to his fellow cops, because it means he does not look away when some of them bend the rules.

So why should we watch him? First, because he’s an underdog in his community. We like underdog stories (e.g., Rudy, Rocky). Second, because he’s good at his job. We like to see characters being competent in their work. This comes out as Exley questions three suspects in the Nite Owl shooting, getting admissions with skill, not violence (IOW, the opposite of Bud).

Lesson: A good Lead should have a skill or power that can be his deliverance at a critical point.

Jack Vincennes (Kevin Spacey) is slick, a charmer. He knows how to skirt the system and rake in a little illicit dough on the side. He takes money from the slimy Sid Hudgeons (Danny DeVito) to bust the victims of Sid’s amorous setups to feed his scandal magazine Hush Hush. But Jack’s favorite side hustle is as the technical advisor on the TV show “Badge of Honor” (i.e., “Dragnet”).

Lesson: A Lead who skates along the dark side should have some charm. We like lovable rogues.

Mirror Moments

Each one of these Leads goes through a personal and positive transformation. As I watched the movie again, I naturally wondered if there would be any mirror moments.

Turns out there’s three of them.

Not only that, two of them involve actual mirrors! (I love it when that happens).

For Bud White, it’s when he’s at the abandoned motel with his captain and some other strong-arm cops. They’re beating up another out-of-town gangster. Bud goes into the bathroom to splash some water on his face. And looks at himself in the mirror. He’s thinking: “Is this who I am? Is this what it means to be a cop?”

Jack Vincennes has just taken another fifty-dollar-bill to show up at a motel where Sid has engineered his biggest scoop yet—the District Attorney of Los Angeles in bed with a handsome young actor (Simon Baker). Sid has paid the kid to seduce the D.A., but also enlisted Jack to promise him a nice part on an episode of “Badge of Honor.” A promise Jack never intends to keep.

While waiting for the appointed hour, Jack sits in a bar and looks at himself in the bar mirror. He’s disgusted. “Is this who I am? Is this what it means to be a cop? Do I really care nothing about lying to an innocent kid who just wants to make it in this town?”

He lays the fifty down on his unfinished drink and leaves to go warn the kid to get out of the room….but instead finds him slain. The consequences of this will lead to one of the great shock twists in cinema (you’ll have to watch the movie to find out, and please, if you know what I’m talking about, do NOT spoil it in the comments).

The mirror moment for Edmund Exley comes when he is awarded the Medal of Valor for his part in slaying the suspects in the Nite Owl murders. In the script he tells his Captain, Dudley Smith (James Cromwell) something feels wrong about the case. Smith tells the new hero, “Keep it inside. Between you and you.”

The very definition of a mirror moment! Exley considers his medal. The script says, “It’s an appealing thing.” He can stay a hero by keeping quiet. But at the cost of justice. Which way will he go?

That’s the question a mirror moment asks.

Lesson: Done skillfully, the mirror moment subconsciously deepens the viewing—and reading—experience.

Dialogue

Period slang and cop jargon are sprinkled throughout, though not so much that it’s distracting. A good lesson there when your write a period piece. A little slang goes a long way. You’re not going for total authenticity (you never are when you write dialogue). You’re trying to create an effect for the reader. Don’t let jargon get in the way of the story.

Speaking of which, my views on the ol’ F bomb are well known, and while this is a James Ellroy, I think the film would’ve been helped with more restraint in this area.

And with that, I turn it over to you.

Have you written a novel with more than one POV? How’d it work for you?

Have you written about your home town—or a fictional place just like it—in a book?

Thumbs up or thumbs down on L.A. Confidential?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

In his early years as a writer, Ray Bradbury made lists of nouns based on childhood memories. Things like: The Lake, The Night, The Crickets, The Ravine.

In his early years as a writer, Ray Bradbury made lists of nouns based on childhood memories. Things like: The Lake, The Night, The Crickets, The Ravine.

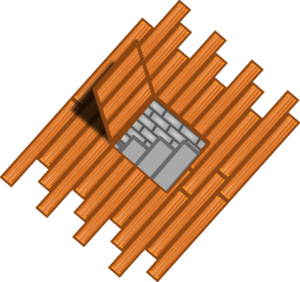

“These lists were the provocations,” he wrote in Zen in the Art of Writing, “that caused my better stuff to surface. I was feeling my way toward something honest, hidden under the trapdoor on the top of my skull.”

I love that metaphor of the trapdoor. We need to flip that door open and shine a light down where all the “better stuff” is.

What did Bradbury mean by that? I think he meant what comes from deep, emotional resonance. It’s what you can’t put into words to define it; but what you must put into words to create it—first for you, then for your reader.

I’ve written some scenes that I’ve gotten emails about. When I look at those I find inevitably they came to me after I opened the trapdoor.

How do you do that?

You make a list like Bradbury’s. Find some time to get alone, take a some deep breaths, and just start remembering….write down all the images and smells and sounds that come to mind. Don’t judge any of it. You’re recording, not fictionalizing. When you get tired, take a break, then come back and add to this list. Put it aside for awhile. Then read it over and highlight the words that generate the most emotion inside you.

I guarantee you’ll find story gold. You can transmute those feelings into your Lead character. You can create moments in your book that will connect with readers in a powerful way. You can also mine the list for short story subject matter. That’s what I like to do most with my own list. (Hat tip to Dale for yesterday’s post which prompted this one.)

I was looking at my list a few years ago when I stopped on The Cigar. That word was there because of my father. To this day when I get a whiff of cigar smoke, I think of Dad. This time when I read the word I flashed back to a scene from my own life, involving me, a liquor store, and a box of Dutch Masters. The emotion of what happened—embarrassment—gave me an idea for a short story called “My Father’s Birthday.”

I published it. And apparently that emotional resonance I mentioned above was there for many readers. If you’ll allow me two clips from the reviews:

Then, in only 12 pages, he ties all his plot threads together to impart an emotional impact that a lot of authors wouldn’t be able to do in a book-length memoir. Indeed, other writers could have turned the bares storyline of “My Father’s Birthday” into an entertaining short story. Few could produce one with the same lasting impact.

***

I’m telling you, this author has the power to take a person on an emotionally resonant trip down memory lane.

I show you those simply to demonstrate what opening the trapdoor on top of your skull can do for a story. If you’d like to read the story itself, I’ve made it free today for your Kindle or Kindle app. Click here. Outside the U.S., go to your Amazon site and search for: B081THHSYL

Try this: Right now, write down three nouns from your childhood, pictures under your trapdoor. Go ahead. I’ll wait.

Now pick one of them and share it with us. Why that word? What’s the emotional resonance for you? Have you used it in one of your stories?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Some years ago I make a list of the things I wanted front-of-mind as I wrote. Here is that list, with some added commentary.

Some years ago I make a list of the things I wanted front-of-mind as I wrote. Here is that list, with some added commentary.

EMOTION! That’s what your readers want! YOU must be moved in order to move your readers. WRITE WITH EMOTION!

One of the first truths about writing fiction I picked up from Sol Stein. He emphasized that the best fiction was first and foremost an emotional experience. You can have a clever plot with all sorts of twists and turns, but if the readers don’t care about the characters emotionally, it’s all for naught.

One of the things I do before I write a scene is get myself into the mood of the scene. The best way for me to do this is listen to music. I have several playlists made up mainly of movie soundtracks. If I’m going to write suspense, I’ll put on some Bernard Herrmann (Hitchcock’s favorite). If it’s deeply felt emotion in the character, I’ll choose something another movie, like A River Runs Through It or October Sky. And so on.

Better to put too much emotion in first draft, and cut back, than not enough and puff up.

Further, if I really want to capture strong emotion, I’ll open up a fresh doc and just write intensely and fast, forgetting grammar, sometimes producing a page-long sentence. Then I sit back and choose the best nuggets. Sometimes it’s only one line, but it’s one I wouldn’t have come up with without overwriting.

Major in conflict: Physical and emotional.

We all know conflict is the engine of fiction. This is just a reminder to keep piling on the trouble.

Always write lists of possibilities. Search for originality.

When it comes to making a choice of where to go in a scene or how to describe something, I’ll make a quick list of possibilities, pushing myself to avoid the clichés and stereotypes. It doesn’t take long to do this and the payoff is well worth it.

Write with eyes closed for description.

Before describing a location, I’ll close my eyes and let my imagination roam around like a movie camera. What is it showing me? I keep looking for original items. One “telling detail” is better than a dozen standard images.

Unanticipate. What would readers expect? Don’t give it to them.

Be aware of what the average reader might think will happen next. Then don’t do that thing!

STAY LOOSE! Always be learning the craft, but when you write, write fast and loose. Like Fast Eddie Felson plays pool.

You all know I believe in craft study. I credit it for my initial breakthrough and whatever success I’ve managed to have. But when I’m doing the writing itself, I don’t think about anything other than the emotion and conflict in front of me. Fast Eddie Felson is the character Paul Newman plays in one of the great American movies, The Hustler. When he has his big showdown with Minnesota Fats, which comes at a great personal cost, he says he’s not going to play it safe anymore. “Fast and loose,” he says, and proceeds to run the table.

When in doubt, freak the character out.

This is sort of a corollary of that famous Raymond Chandler idea that when you don’t know what to do next, bring in a guy with a gun. Do something that rattles the character’s world, turns things upside down.

Start a scene a bit later. End it a bit sooner.

This works wonders for readability and page-turning. Look at your chapter openings, and see if you can jump into the scene a beat or two later. Instead of setting up with description, give us dialogue and action. You can always drop back and describe later.

Then look at your chapter endings. See if you can cut the last line or two, or even paragraph. The feeling of momentum will prompt the reader to keep going.

Showing two conflicting emotions in a character heightens the tension and deepens the scene.

Often we give a character an emotional response that is rather predictable. Not that it is necessarily wrong. But, as with unanticipation, try to work in another emotion, unexpected and in conflict with the first. Readers are really drawn to emotional cross-currents. You will create a moment that is highly original.

SUES: Something unexpected in every scene, even if it’s just one line of odd dialogue.

Again, what makes for a boring or forgettable fiction experience? It’s when a reader subconsciously guesses what will happen next…and it does.

But when they are surprised, their interest skyrockets.

You can find a spot in every scene to drop in something they don’t see coming.

One of my favorite ways is to have a character say something that seems so off the wall that it doesn’t fit, then find a way to have it make sense.

There you have it. My favorite reminders. What about you? What would you add to this list?

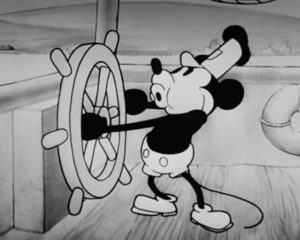

The Mouse formerly known as Mortimer.

Steamboat Willie, the first Disney synchronized-sound cartoon, is now in the public domain. The 1928 short features Mickey Mouse (whom Walt was going to call Mortimer, until his wife voted thumbs down). Anyone can now use this version of Mickey…but not the later one where he’s put on a little weight and sports white gloves. You also can’t imply that your use is sanctioned by Disney corporate. The rules are spelled out here. A list of some of the prominent works now open to all is here.

Here’s something to look forward to: Seventy years after your death, your works will enter the public domain. So let’s go to a day in the future when a browser with a virtual reality headset happens across one of your books and decides to look up who you were. What would you like your short bio to say? Put it in the form of “[Your Name] was a writer known for ____” and go from there!

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

’Tis the season for Christmas spice. Starbucks has reissued the ever-popular Pumpkin Spice Latte. All over the land people are dipping into their children’s college fund to buy the brew.

’Tis the season for Christmas spice. Starbucks has reissued the ever-popular Pumpkin Spice Latte. All over the land people are dipping into their children’s college fund to buy the brew.

It’s also the season for Christmas movies. It’s been a tradition in the Bell family to gather around the hearth…I mean TV…after the Thanksgiving meal to kick off the season. Not with football, but with a classic Christmas movie. Doesn’t matter that we’ve seen it many times before. We’re always delighted, and there’s a good reason for that. I shall explain anon.

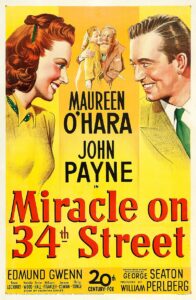

But first, here are our top three: Miracle on 34th Street (1947 version only), A Christmas Carol (1951 Alastair Sim version), and It’s a Wonderful Life.

Honorable mention goes to: Die Hard, Lethal Weapon (both, of course, take place at Christmastime), Home Alone, A Christmas Story, The Santa Clause, and Elf. If we’re feeling particularly silly, we’ll pop in Ernest Saves Christmas.

What is it about these movies that warms the cockles of the heart? [Note: The cockles of the heart are its ventricles, named by some in Latin as “cochleae cordis”, from “cochlea” (snail), alluding to their shape. The saying means to warm and gratify one’s deepest feelings.] Of course, most of it is the story itself, uplifting in its own way. A Christmas Carol tells us no one is beyond redemption. It’s A Wonderful Life literally spells out: No man is a failure if he has friends. Die Hard: One New York cop is better than a whole a gang of European terrorists. Etc.

But there’s something else in the best of these movies. I call it the spice of fiction: minor characters. Like nutmeg on your nog or cloves on your honey-baked ham, they up the pleasure. Let me give you three examples.

Thelma Ritter as the ticked-off mother in Miracle on 34th Street

This story has a great premise: What if a department store Santa was the real Santa Claus?

The main characters are perfectly cast. Edmund Gwenn as Kris Kringle won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. Maureen O’Hara was never lovelier; John Payne shows off his light comedy chops; and little Natalie Wood is, as they used to say, cute as a button.

The film is filled with spicy minor characters: the judge overseeing Kringle’s mental health hearing (Gene Lockhart); his political advisor (William Frawley); Alfred, the Macy’s janitor whom Kringle befriends (Alvin Greenman). There’s even one bit in one scene that never gets old. Mrs. Shellhammer (Lela Bliss), the wife of the head of Macy’s toy department, has been plied with “triple strength” martinis by her husband, hoping to get her to consent to having Kringle move in with them. She is completely blitzed as she tries to talk on the phone. Cracks us up every time.

My favorite, though, is the great character actress Thelma Ritter in her very first film role. She’s shopping at Macy’s and lets her little boy chat with Santa. The following ensues:

Later, she tracks down Mr. Shellhammer and compliments him on this “new stunt” they’re pulling. Sending people to other stores! “Imagine a big outfit like Macy’s putting the Christmas spirit before the commercial.” She tells him she is now a dedicated Macy’s shopper.

Kathleen Harrison as Scrooge’s charwoman in A Christmas Carol

Scrooge, of course, mistreats those around him, from his meek clerk Bob Cratchit, to his nephew, to the two gentlemen collecting for charity:

“Are there no prisons?” asked Scrooge.

“Plenty of prisons,” said the gentleman, laying down the pen again.

“And the Union workhouses?” demanded Scrooge. “Are they still in operation?”

“They are. Still,” returned the gentleman, “I wish I could say they were not.”

“The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?” said Scrooge.

“Both very busy, sir.”

“Oh! I was afraid, from what you said at first, that something had occurred to stop them in their useful course,” said Scrooge. “I’m very glad to hear it.”

And then there is his poor domestic, Mrs. Dilber, whom he underpays and overworks. But on Christmas morning he is a changed man, and Sim spectacularly shows us the transformation. But almost stealing the scene is Miss Harrison:

Bert and Ernie serenade George and Mary in It’s a Wonderful Life

No, not the Sesame Street characters. Bert the cop (Ward Bond) and Ernie the cab driver (Frank Faylen) are friends of George Bailey (James Stewart). George and Mary (Donna Reed) have just gotten married, but George has to stop a run on the Bailey Building and Loan by using all the money he has saved up to take Mary on a honeymoon. Offscreen, while the crisis is being averted, Mary—with the help of Bert and Ernie—arranges for a honeymoon night in an old abandoned house she’s always loved. The astonished George arrives. It’s raining. The house leaks. But there’s a fire and a record player going. That would be a nice, romantic scene on its own, but the addition of Bert and Ernie serenading makes it perfect:

Spend time with your minor characters this season. Make them unique. Allow them to surprise you. Spice up your WIP.

Merry Christmas

Prospero Año y Felicidad

And we’re out. See you right back here on January 1, 2024!

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

In her excellent recent post Kris wrote:

In her excellent recent post Kris wrote:

I know you’re tempted to dismiss theme as mere enhancement. Le cerise sur la gateau, as the French say. But it’s essential. Try this experiment: Write the back copy for your work in progress — three paragraphs at most. Ha! Can’t do it? Well, you might not have a grip on what your story is about at its heart. Now often your theme doesn’t show itself until you’re well into your plot. Well, that’s okay. But when it begins to whisper, listen hard. Good fiction, Stephen King says, “always begins with story and progresses to theme.”

No matter what you do, your book will have a theme (or meaning) at the end.

Because your characters carry a theme. Always.

Do the good guys win? Justice will triumph.

Do the bad guys win? Justice is a myth. (This is the theme of Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors.)

So: you can set out to say something, or can wait to see what you’re saying. But say something you will.

As Viktor Frankl puts it in his classic book on the subject, “Man’s search for meaning is the ultimate motivation in his life.” It is a subconscious reason readers pick up books. In the fictional search, they also are exploring their own inner territory.

Vision

Develop a vision for yourself as a writer. Make it something that excites you. Turn that into a mission statement—one paragraph that sums up your hopes and dreams as a writer. Read this regularly. Revise it from time to time to reflect your growth.

Root that inspiration in the world—your observations of it, and what it does to you. “I honestly think in order to be a writer,” says Anne Lamott, “you have to learn to be reverent. If not, why are you writing? Why are you here? Let’s think of reverence as awe, as presence in and openness to the world.”

If you stay true to your own awe, your books cannot help but be charged with meaning. That’s not just a great way to write. It’s a great way to live.

What Theme Is

Theme is a statement about life. It can be implicit or explicit, subtle or overt. But it must come through fully realized characters engaged in a believable plot. Otherwise the book will come across as a thinly veiled essay, sermon, or jeremiad.

Now, there is nothing wrong with “message fiction.” In message fiction an author says to the reader: I have strong, heartfelt beliefs about this issue — and I think I know what the truth is. I’m going to reveal that truth in this novel, through the lives of these characters, and I hope to convince you to believe as I do. It’s not a matter of shades of grey. There is a right and a wrong here, and everything depends on my convincing you to cling to the right.

But the key word here is not message; it’s fiction. If your book doesn’t work as a story, the message will fall flat.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is message fiction. So is To Kill a Mockingbird. The Narnia books of C.S. Lewis are message fiction, but they work as engaging stories with characters we care about.

Donald Maass says:

A breakout novelist believes that what she has to say is not just worth saying, but it is something that must be said… Strong novelists have strong opinions. More to the point, they are not at all afraid to express them.

But the key word here is not message; it’s fiction. If your book doesn’t work as a story, the message will fall flat.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is message fiction. So is To Kill a Mockingbird. The Narnia books of C.S. Lewis are message fiction, but they work first as engaging stories with characters we care about.

Try This:

Over to you now. Do you think about theme before you begin to write? Or do you let it emerge as you go? Or do you not think about it at all?

Is there a theme you see recurring in your writing?

This post is brought to you by the audio version of The Mental Game of Writing. I was invited to try Kindle Direct Publishing’s beta of “virtual voice” narration. Since I have narrated a few of my writing books, this is an experiment in saving massive amounts of time. What took me 10-15 hours before (narrating, editing, etc.) now takes 10-15 minutes to set up and go live. You can listen to a sample of the result here.