I just saw a recent analysis by Booklr of the top 100 Amazon Kindle books versus the top 100 Barnes & Noble Nook titles in respect of their relative price points. The results are, I think pretty interesting for anyone considering ‘indie’ publishing, and in demonstrating the role price may play in different e-book ‘markets’.

According to the Booklr survey 35% of the top 100 books on Kindle were free or priced under $2 compared to 0% for the Nook. 61% of the top 100 books on Kindle were priced under $6 versus 39% on the Nook. In the higher price bracket, the results are also pretty different with 27% of books on Kindle priced above $10 versus 40% on the Nook.

These results suggest that customers have quite different book buying habits in these two ‘e-reader’ markets. It also points to a potential new culture for the Kindle in which customers tend to buy what is free or less than $2. As an author, this signals to me that if I was to go the ‘indie’ route, I would need to consider price very, very carefully indeed.

The Booklr analysis indicates that the average price for a Kindle top 100 e-book is $6.48 compared with $8.94 for the Nook – which gives us a rough gauge of the price differential between customers for both platforms and opens up the debate over the impact of free and cheap (99c) e-books on overall pricing trends.

So for all your authors considering the indie route, how are you approaching the issue of price? If you are traditionally published, what kind of price point has your publisher set for your e-book? And how much influence do you think Amazon is going to have on driving e-book prices down?

Author Archives: Joe Moore

Ebook Prices

I just saw a recent analysis by Booklr of the top 100 Amazon Kindle books versus the top 100 Barnes & Noble Nook titles in respect of their relative price points. The results are, I think pretty interesting for anyone considering ‘indie’ publishing, and in demonstrating the role price may play in different e-book ‘markets’.

According to the Booklr survey 35% of the top 100 books on Kindle were free or priced under $2 compared to 0% for the Nook. 61% of the top 100 books on Kindle were priced under $6 versus 39% on the Nook. In the higher price bracket, the results are also pretty different with 27% of books on Kindle priced above $10 versus 40% on the Nook.

These results suggest that customers have quite different book buying habits in these two ‘e-reader’ markets. It also points to a potential new culture for the Kindle in which customers tend to buy what is free or less than $2. As an author, this signals to me that if I was to go the ‘indie’ route, I would need to consider price very, very carefully indeed.

The Booklr analysis indicates that the average price for a Kindle top 100 e-book is $6.48 compared with $8.94 for the Nook – which gives us a rough gauge of the price differential between customers for both platforms and opens up the debate over the impact of free and cheap (99c) e-books on overall pricing trends.

So for all your authors considering the indie route, how are you approaching the issue of price? If you are traditionally published, what kind of price point has your publisher set for your e-book? And how much influence do you think Amazon is going to have on driving e-book prices down?

A New Definition of Writing Success

There was one primary reason for all this distress: Their fate as writers was not in their own hands. To get anywhere close to “success” they had to be accepted by an established publishing house (which alone had the means to produce and distribute a book), and then hope that they earned some money for their efforts.

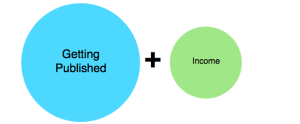

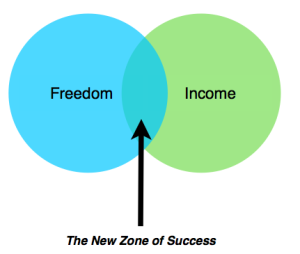

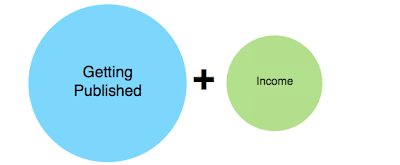

Yet income alone is not the main draw of this new model, which looks like this:

This does not mean that going the traditional route is a spurious view of “success.” If one seeks that validation, it’s there to be pursued. The point is, however, that it is no longer the only game in town. Which is why I am more jazzed about being a writer than ever. Not just because of increased production and income, but because of the freedom to take responsibility for my own work.

I can say this because, in one of life’s ironic and poignant turns, The Fulfilment by Edith Allonby is now available for the Kindle.

A New Definition of Writing Success

There was one primary reason for all this distress: Their fate as writers was not in their own hands. To get anywhere close to “success” they had to be accepted by an established publishing house (which alone had the means to produce and distribute a book), and then hope that they earned some money for their efforts.

Yet income alone is not the main draw of this new model, which looks like this:

This does not mean that going the traditional route is a spurious view of “success.” If one seeks that validation, it’s there to be pursued. The point is, however, that it is no longer the only game in town. Which is why I am more jazzed about being a writer than ever. Not just because of increased production and income, but because of the freedom to take responsibility for my own work.

I can say this because, in one of life’s ironic and poignant turns, The Fulfilment by Edith Allonby is now available for the Kindle.

You can’t teach a cat to sing or a dog to fly.

John Ramsey Miller

I’m not here on every other Saturday to teach anybody how to write. Others here know the technicalities and can teach you or sell you books about the craft. I’m not blogging here to make what I do seem mysterious, or harder than it is, and it ain’t at all hard for a real writer. I’ll just say for you to keep your story moving. Make your characters real. Your style should be to write like you’d tell a story to an audience. Work hard to write a story you’d like to read. And think hard about your story before you write it down. That is all I can tell anyone. I expect that anything else I say is a rule is bullshit I’m making up. That’s all about it I actually know, I’ve read Elmore Leonard’s list and Stephen King’s book, and BIRD IN HAND, and I didn’t agree or disagree. That is what they think, or think they think or want me to think they think. The process is different for everybody. Some authors will say they have no idea how they do what they do. I think most famous authors are surprised they are famous for what they wrote.

I’m not in on any authoring secrets, and I worked the steps everybody has to work in order to be published, and I had no contacts in the writing community. I wasn’t discovered sitting in my studio by talent scouts, I worked damned hard. No known writer reached down, took my hand and dragged me to their publisher and demanded they publish me of they would take their money generating words elsewhere. So work your ass off or get away from this profession now.

If you can write a book that people will actually buy without being related to you, or your shamelessly flogging it to them in a crowded bar at Bouchercon, you are in the vast minority. I never say, “if I can do it anybody can,” because it is one of those things you either can or you can’t do. Anybody on earth can write badly and most do. I know high school dropouts who write brilliantly. I know learned writing professors whose books can suck lint off a cheap sweater at fifty yards. There are no shortcuts I can impart, or secrets to being published. Write a very good book and push it to the right people at the right time. I don’t know who that is, because it is different for every author. Hell, just publish it somewhere yourself and say you wrote a book. There are millions of people singing not very well on You Tube.

I didn’t set out to become an author. From an early age I wrote short stories, poems, and I did so for my own entertainment and as a way to express myself. People have always fascinated me. Stories fascinated me. I was blessed with a natural curiosity and being born in an interesting time and place. Writing found me the same way graphic art and photography did. I was interested in it and I did it for myself first. People I shared my stories with, enjoyed them. My advertising writing sold products. I wrote my first thriller without knowing it was a thriller, or what made any book a thriller. I wrote a fast moving story about violent and complex people. A very talented editor bought it and together we turned it into a very good book.

I have never read one page into a romance novel and I don’t ever intend to. I’ve had dear friends who write them, but I do not care to read any. I have friends who have never read any of my books, and in truth I could care less. Not that I think romance, mystery, or cozy authors have less talent, I’m just not into those genres. There are great writers in those genres and they have their readers, some legions of fans. Kumbaya moments bore me. I don’t like writing them.

My fans have strong stomachs. They like justice, the rougher the better. As far as I can tell, most of my fans are not violent people, but they like to read violence, and they like their violence accurate. The romance I write into my novels is that which is in me. You don’t stay married 35 years without some romance. My written romance isn’t necessarily sentimental, it’s a reflection of my affections and *effections. I can only write convincingly that which is within me.

If I think the story should go there, I will kill both cub scouts and cats without a second thought to the reader’s reaction. Some readers make the association that murdered fictional animals are the real ones they love, which isn’t my problem. The same readers could care less if I kill children. I don’t give a damn. I really don’t.

It is my opinion that most new Thrillers are that they are just rehashes or reshuffles of thrillers that came before them. I know that’s true with other genres as well. You can’t think of an original story because they have all been done. It is the rare twist that Thriller readers or writers don’t see coming before the writer thinks they will. A fresh new story gets harder to write all the time. Early Thriller writers had it good because that wasn’t yet true. Think of books like you might a gun. There are just so many places you can put the barrel. The barrel has to point forward else the shooter is in imminent danger of not living through the shooting experience. The bullet rests in the chamber, which has to be very precisely located behind the barrel. There are a finite number of firing pin, hammer and grip designs to be put with the barrel designs. There are just so many bullet calibers to be put into the mix. So any new gun has more to do with cobbling together varying design elements that have come before them than those that can come after. There will be ray guns and particle beam guns, but those will be less guns than machines that can do what a gun does, only better or differently. Maybe thrillers that are written so differently that they don’t just entertain, but maim or kill the reader as well.

I have been brutal to would-be authors whose work showed no inkling of talent at writing fiction. Other writers think I should encourage everybody who tries. Bullshit. If someone is wasting their time, they should know it so they can follow another dream, or perhaps start bending sheet metal into ducts that might prove useful. It is hard enough when you have some talent or even some mechanical ability with words. If you can’t write fiction, you can become a technical writer, or write non-fiction. But if you can’t write on a fundamental level… Ok, so who am I to judge. I don’t like hurting feelings or dashing dreams. I never asked to be put in a position to judge ability, but when I’m asked to judge, I do. Don’t want to hear it, don’t friggin’ ask. That’s certainly cool with me.

I am not a drum major for deluded people who only dream of being authors to prove something to themselves, to make a quick fortune, to impress their friends, or to allow their egos to bloom. I feel sorry for people who truly love books and have a real desire to contribute their own visions to literature, all the while knowing that is as impossible as me becoming American Idol. Delusions should not be fed, else you’ll have people going postal all over the country. So I like to imagine I’m saving lives by being critical.

Nothing pleases me more than seeing raw talent. If someone has that, I always do my best to encourage and help them any way I can.

You can’t teach a cat to sing or a dog to fly.

John Ramsey Miller

I’m not here on every other Saturday to teach anybody how to write. Others here know the technicalities and can teach you or sell you books about the craft. I’m not blogging here to make what I do seem mysterious, or harder than it is, and it ain’t at all hard for a real writer. I’ll just say for you to keep your story moving. Make your characters real. Your style should be to write like you’d tell a story to an audience. Work hard to write a story you’d like to read. And think hard about your story before you write it down. That is all I can tell anyone. I expect that anything else I say is a rule is bullshit I’m making up. That’s all about it I actually know, I’ve read Elmore Leonard’s list and Stephen King’s book, and BIRD IN HAND, and I didn’t agree or disagree. That is what they think, or think they think or want me to think they think. The process is different for everybody. Some authors will say they have no idea how they do what they do. I think most famous authors are surprised they are famous for what they wrote.

I’m not in on any authoring secrets, and I worked the steps everybody has to work in order to be published, and I had no contacts in the writing community. I wasn’t discovered sitting in my studio by talent scouts, I worked damned hard. No known writer reached down, took my hand and dragged me to their publisher and demanded they publish me of they would take their money generating words elsewhere. So work your ass off or get away from this profession now.

If you can write a book that people will actually buy without being related to you, or your shamelessly flogging it to them in a crowded bar at Bouchercon, you are in the vast minority. I never say, “if I can do it anybody can,” because it is one of those things you either can or you can’t do. Anybody on earth can write badly and most do. I know high school dropouts who write brilliantly. I know learned writing professors whose books can suck lint off a cheap sweater at fifty yards. There are no shortcuts I can impart, or secrets to being published. Write a very good book and push it to the right people at the right time. I don’t know who that is, because it is different for every author. Hell, just publish it somewhere yourself and say you wrote a book. There are millions of people singing not very well on You Tube.

I didn’t set out to become an author. From an early age I wrote short stories, poems, and I did so for my own entertainment and as a way to express myself. People have always fascinated me. Stories fascinated me. I was blessed with a natural curiosity and being born in an interesting time and place. Writing found me the same way graphic art and photography did. I was interested in it and I did it for myself first. People I shared my stories with, enjoyed them. My advertising writing sold products. I wrote my first thriller without knowing it was a thriller, or what made any book a thriller. I wrote a fast moving story about violent and complex people. A very talented editor bought it and together we turned it into a very good book.

I have never read one page into a romance novel and I don’t ever intend to. I’ve had dear friends who write them, but I do not care to read any. I have friends who have never read any of my books, and in truth I could care less. Not that I think romance, mystery, or cozy authors have less talent, I’m just not into those genres. There are great writers in those genres and they have their readers, some legions of fans. Kumbaya moments bore me. I don’t like writing them.

My fans have strong stomachs. They like justice, the rougher the better. As far as I can tell, most of my fans are not violent people, but they like to read violence, and they like their violence accurate. The romance I write into my novels is that which is in me. You don’t stay married 35 years without some romance. My written romance isn’t necessarily sentimental, it’s a reflection of my affections and *effections. I can only write convincingly that which is within me.

If I think the story should go there, I will kill both cub scouts and cats without a second thought to the reader’s reaction. Some readers make the association that murdered fictional animals are the real ones they love, which isn’t my problem. The same readers could care less if I kill children. I don’t give a damn. I really don’t.

It is my opinion that most new Thrillers are that they are just rehashes or reshuffles of thrillers that came before them. I know that’s true with other genres as well. You can’t think of an original story because they have all been done. It is the rare twist that Thriller readers or writers don’t see coming before the writer thinks they will. A fresh new story gets harder to write all the time. Early Thriller writers had it good because that wasn’t yet true. Think of books like you might a gun. There are just so many places you can put the barrel. The barrel has to point forward else the shooter is in imminent danger of not living through the shooting experience. The bullet rests in the chamber, which has to be very precisely located behind the barrel. There are a finite number of firing pin, hammer and grip designs to be put with the barrel designs. There are just so many bullet calibers to be put into the mix. So any new gun has more to do with cobbling together varying design elements that have come before them than those that can come after. There will be ray guns and particle beam guns, but those will be less guns than machines that can do what a gun does, only better or differently. Maybe thrillers that are written so differently that they don’t just entertain, but maim or kill the reader as well.

I have been brutal to would-be authors whose work showed no inkling of talent at writing fiction. Other writers think I should encourage everybody who tries. Bullshit. If someone is wasting their time, they should know it so they can follow another dream, or perhaps start bending sheet metal into ducts that might prove useful. It is hard enough when you have some talent or even some mechanical ability with words. If you can’t write fiction, you can become a technical writer, or write non-fiction. But if you can’t write on a fundamental level… Ok, so who am I to judge. I don’t like hurting feelings or dashing dreams. I never asked to be put in a position to judge ability, but when I’m asked to judge, I do. Don’t want to hear it, don’t friggin’ ask. That’s certainly cool with me.

I am not a drum major for deluded people who only dream of being authors to prove something to themselves, to make a quick fortune, to impress their friends, or to allow their egos to bloom. I feel sorry for people who truly love books and have a real desire to contribute their own visions to literature, all the while knowing that is as impossible as me becoming American Idol. Delusions should not be fed, else you’ll have people going postal all over the country. So I like to imagine I’m saving lives by being critical.

Nothing pleases me more than seeing raw talent. If someone has that, I always do my best to encourage and help them any way I can.

Lesson From Gun Camp

Lesson From Gun Camp

Designing a Thriller – Guest Post Virna DePaul

Host – Jordan Dane

I’m thrilled to host my friend, Virna DePaul. Virna is an esteemed member of the International Thriller Writers and recently interviewed me for ITW’s wonderful e-newsletter for my latest release, but Virna and I had met once before at a Romance Writers of America annual conference. We struck up a conversation at a Karen Rose workshop on writing suspense and had lunch after. At the time, Virna hadn’t sold yet, but she left a good impression on me that she was determined to succeed. Boy has she ever. Welcome Virna DePaul, TKZers!

Thank you to the Kill Zone and in particular Jordan Dane for having me as a guest today!

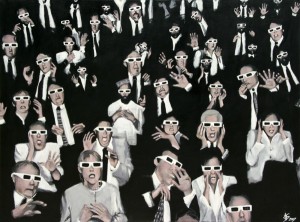

Roller coaster rides. Haunted houses. Horror flicks. And of course, suspense and thriller novels. What do they have in common? They scare us, yet there’s always a certain number of riders, participants, and readers willing to go back for more. Again and again, we seek out experiences that make our hearts race, and alternately tighten our muscles with anticipation and make us dizzy with relief. Why?

Because these experiences affirm our existence even as they wash away its ordinariness. They give us the illusion of being out of control and ultimately triumphant even as we remain both safe and, let’s face it, relative victims to the whims of fate.

We’ll board a roller coaster only because we know the ride will be quick and we can choose to never ride it again. We’ll see a horror movie only because we know we can walk out of the movie theater or cover our eyes at any time. And we’ll read a thriller novel only because we know we can put the book down until we’re ready to dive back in.

Of course, the key to any great thriller experience is that even given these options, we are swept away in spite of ourselves. We forget reality and simply soak in the larger-than-life wonder of the moment. We feel, we agonize, and we rejoice even as some part of our brains know we’re being manipulated by words, images, or mechanical engineering.

I write romance, both contemporary and paranormal, but my novels always have a suspense element in them. Much like a roller coaster architect, I enjoy designing a thrill ride for my audiences. I take into consideration who they are, what their expectations are, and how I can mix things up to bring them something fresh and new. I wield plot to provide suspension, loops, or a straight drop. I use characters to transport a reader to another time and place, keeping her safe even as I provide her maximum thrill and catharsis. I especially like knowing that at the end of my novels, readers will always have a happily-ever-after in the romance plot. And finally, I enjoy the fact that despite being the architect of my novels, I embark on a wondrous journey, too.

In my Para-Ops series, I take my readers from Washington D.C to North Korea to Los Angeles to France. I introduce them to an elite special ops team comprised of a vampire, werebeast, mage, and wraith. In my contemporary novels, I explore the world of undercover cops and state special agents who chase down drug lords and murderers. But always, no matter the genre or the specific plot, I strive to give my readers two things: a thrilling ride that sweeps them away, and enough satisfaction and hope at the end of the story that they can’t help but want to take the ride again.

How about you? Do you seek out thrills just in books or other places, too?

Experience Virna DePaul’s “intriguing world” protected by an elite Para-Ops team with a unique set of skills. In Virna’s latest release, Chosen By Sin (Para-Ops #3), you’ll meet a werebeast hero, a vampire heroine, and a host of other paranormal creatures such as a mage, human psychic, wraith (ghost), demons, and dragons. You can learn more about Virna and her series at www.virnadepaul.com and http://www.chosenbysin.com/.

Virna DePaul is a former criminal prosecutor and now national bestselling author for Berkley (paranormal romantic suspense), HQN (single title romantic suspense; Shades Of Desire (Special Investigations Group Book #1, June 2012)) and HRS (category romantic suspense; It Started That Night (May 2012)). Writers, join Virna’s mailing list to access her archive of monthly writing “cheat sheets.”

Virna DePaul is a former criminal prosecutor and now national bestselling author for Berkley (paranormal romantic suspense), HQN (single title romantic suspense; Shades Of Desire (Special Investigations Group Book #1, June 2012)) and HRS (category romantic suspense; It Started That Night (May 2012)). Writers, join Virna’s mailing list to access her archive of monthly writing “cheat sheets.”Blurb from Chosen By Sin:

The longest life isn’t always the happiest one…

Five years after the Second Civil War ends, humans and Otherborn—humanlike creatures with superhuman DNA—still struggle for peace. To ensure the continued rights of both, the FBI forms a Para-Ops team with a unique set of skills.

For now, werebeast Dex Hunt serves on the Para-Ops team, but his true purpose is to kill the werewolf leader he blames for his mother’s death. Biding his time, Dex keeps his emotional distance from his team members and anyone else he might care for, including a mysterious vampire he met in L.A.

Buy the book HERE.

Writing is Rewriting

By Joe Moore

I just finished the first draft of my new thriller, THE BLADE, co-written with Lynn Sholes. This is our sixth novel written together; this one coming in at a crisp 92,500 words. Now that the first pass on the manuscript is finished, the rewrite begins. As E.B. White said in THE ELEMENTS OF STYLE, “The best writing is rewriting.”

Some might ask that if the manuscript is written, why do we need to rewrite it? Remember that the writing process is made up of many layers including outlining, research, first drafts, rewriting, line editing, proofing, more editing and more proofing. One of the functions that sometimes receives the least amount of attention in discussions on writing techniques is rewriting.

There are a number of stages in the rewriting process. Starting with the completion of the first draft, they involve reading and re-reading the entire manuscript many times over and making numerous changes during each pass. It’s in the rewrite that we need to make sure our plot is seamless, our story is on track, our character development is consistent, and we didn’t leave out some major point of importance that could confuse the reader. We have to pay close attention to content. Does the story have a beginning, middle and end? Does it make sense? Is the flow of the story smooth and liquid? Do our scene and chapter transitions work? Is everything resolved at the end?

Next we need to check for clarity. This is where beta readers come in handy. If it’s not clear to them, it won’t be clear to others. We can’t assume that everyone knows what we know or understands what we understand. We have to make it clear what’s going on in our story. Suspense can never be created by confusing the reader.

Once we’ve finished this first pass searching for global plotting problems, it’s time to move on to the nuts and bolts of rewriting. Here we must tighten up our work by deleting all the extra words that don’t add to the reading experience or contribute to the story. Remember that every word counts. If a word doesn’t move the plot forward or contribute to character development, it should be deleted.

Some of the words that can be edited out are superfluous qualifiers such as “very” and “really.” This is always an area where less is more. For instance, we might describe a woman as being beautiful or being very beautiful. But when you think about it, what’s the difference? If she’s already beautiful, a word that is considered a definitive description, how can she exceed beautiful to become very beautiful? She can’t. So we search for and delete instances of “very” or “really”. They add nothing to the writing.

Next, scrutinize any word that ends in “ly”. Chances are, most adverbs can be deleted without changing the meaning of the sentence or our thought. In most cases, cutting them clarifies and makes the writing cleaner.

Next, go hunting for clichés and overused phrases. There’s an old saying that if it comes easy, it’s probably a cliché. Avoiding clichés makes for fresher writing. There’s another saying that the only person allowed to use a cliché is the first one that use it.

Overused phrases are often found at the beginning of a sentence with words like “suddenly,” “so” and “now”. I find myself guilty of doing this, but those words don’t add anything of value to our writing or yours. Delete.

The next type of editing in the rewriting process is called line editing. Line editing covers grammar and punctuation. Watch for incorrect use of the apostrophe, hyphen, dash and semicolon. Did we end all our character’s dialogs with a closed quote? Did we forget to use a question mark at the end of a question?

This also covers making sure we used the right word. Relying on our word processor’s spell checker can be dangerous since it won’t alert us to wrong words when they are spelled correctly. It takes a sharp eye to catch these types of mistakes. Once we’ve gone through the manuscript and performed a line edit, I like to have someone else check it behind us. A fresh set of eyes never hurts.

On-the-fly cut and paste editing while we were working on the first draft can get us into trouble if we weren’t paying attention. Leftover words and phrases from a previous edit or version can still be lurking around, and because all the words might be spelled correctly or the punctuation might be correct, we’ll only catch the mistake by paying close attention during the line edit phase.

The many stages making up the rewrite are vital parts of the writing process. Editing our manuscript should not be rushed or taken for granted. Familiarity breeds mistakes—we’ve read that page or chapter so many times that our eyes skim over it. And yet, there could be a mistake hiding there that we’ve missed every time because we’re bored with the old stuff and anxious to review the new.

Spend the time needed to tighten and clarify the writing until there is not one ounce of fat or bloat. And once we’ve finished the entire editing process, put the manuscript away for a reasonable period of time. Let it rest for a week or even a month if the schedule permits while working on something else. Then bring it back out into the light of day and make one more pass. It’s always surprising at what was missed.

One more piece of advice. Edit on hardcopy, not on a computer monitor. There’s something about dots of ink on the printed page that’s much less forgiving than the glow of pixels. And never be afraid to delete. Remember, less is always more.

How do you go about tackling the rewriting process? Any tips to share?