Mr. Harlan Ellison, a writer who has never been known as a shrinking violet, once had a slight disagreement with his publisher. That incident is recounted here.

Tell us, have you ever wanted to react just that way? What were the circumstances? How did you handle it? What would you counsel a young writer regarding when to be, er, demonstrable in his or her ire?

Monthly Archives: May 2013

First Page Critique: Heart Failure

James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Self-Discipline for the Writer

Nancy J. Cohen

Writers sit in a chair for hours, peering at their work, blocking out the rest of the world in their intense concentration. It’s not an easy job. Some days, I marvel that readers have no idea how many endless days we toil away at our craft. It takes immense self-discipline to keep the butt in the chair when nature tempts us to enjoy the sunshine and balmy weather outside.

We don’t only spend the time writing the manuscript. After submitting our work and having it accepted, we get revisions back from our editor. This requires another round of poring over our work. And another opportunity comes with the page proofs where we scrutinize each word for errors. How many times do we review the same pages, the same words? How many tweaks do we make, continuously correcting and making each sentence better?

These hours and hours of sitting are worth the effort when we hold the published book in our hands, when readers write to us how much they enjoyed the story, or when we win accolades in a contest. As I get older, I wonder if these hours are well spent. My time is getting shorter. Shouldn’t I be outside, enjoying what the community has to offer, admiring the trees and flowers, visiting with friends? Each moment I sit in front of the computer is a moment gone.

But I can no more give up my craft than I can stop breathing. It’s who I am. And the hours I sit here pounding at the keyboard are my legacy.

BICHOK is our motto: Butt in Chair, Hands on Keyboard. This policy can take its toll on writers’ health with repetitive strain injury, adverse effects of prolonged sitting, neck and shoulder problems. We have to discipline ourselves not only to sit and work for hours on end, but to get up and exercise so as to avoid injury. This career requires extreme discipline, and those wannabes who can’t concentrate for long periods of time or who give up easily will never reach the summit. They can enjoy the journey and believe that’s where it ends, but they’re playing at being a writer and not acting as a professional.

We’re slaves to our muse, immersed in our imaginary worlds, losing ourselves to the story. And then we have to revise, correct, edit, read through the manuscript numerous times until we turn it in or our vision goes bleary. We are driven. And so we sit, toiling in our chairs (or on the couch if you use a laptop). Hours of life pass us by, irretrievable hours that we’ll never get back.

So please, readers, understand how many hours we put into this craft to entertain you, to educate you, and to illuminate human nature in our stories.

And this doesn’t even count the time required for social media.

I put myself in the chair until I achieve a daily quota. In a writing phase, this is five pages a day or twenty-five pages per week. For self-edits, I aim for a chapter a day but that’s not always possible. I do this is the morning when I’m most creative. Afternoons are for writing blogs, social media, promotion, etc.

How do you get yourself to sit in the chair day after day? Do you set daily goals? Do you offer yourself rewards along the way? Do you ever doubt the time you sacrifice to your muse? Or do you love the process so much that you’d not trade those hours for anything else?

<><><>

I’m currently running a blog tour. If you wish to join me, please click here. Leave a comment for a chance to win prizes.

Also, if you wish to enter my current contest, Go Here.

Writers and their canine doppelgangers

So I was walking my dog on the boardwalk in Hermosa Beach the other day, totally MMOB, when I was hailed by a couple of guys clutching beers in paper bags.

I considered the question. My dog MacGregor is a serious-looking guy, long and lean, like a black wolf. I am none of those things, except I was wearing a black jogging suit. But with my blonde hair and general demeanor, I would say I’m more of a Golden Retriever.

I considered the question. My dog MacGregor is a serious-looking guy, long and lean, like a black wolf. I am none of those things, except I was wearing a black jogging suit. But with my blonde hair and general demeanor, I would say I’m more of a Golden Retriever.

Hunting Down The Muse

I’m in a situation that I haven’t been in for four years. Now that I’ve delivered my latest book, I’m no longer under contract to a publisher expecting my next novel. This is the first time since I signed my first publishing contract in 2009 that I don’t have a hard deadline. It’s both a scary and liberating scenario because I have to decide what to write next.

Like every other author, I often get the dreaded question, Where do you get your ideas? I can usually come up with a response that sounds reasonable and interesting, but the real answer is that I don’t know where they come from. I wish I did. It would make everything so much easier. I wish I could flip a switch in my mind that goes, “Okay, Brain, time for the next idea. What sounds good to you?”

Instead, Brain usually tells me to buzz off. It’s much too busy forcing me to watch TV or worrying about whether I forgot to lock the car when I left it in the mall parking lot. Other times, Brain is throwing ideas at me left and right, many of which are versions of stories that have already been done, but dumber.

Brain: Hey, what about a book about a sea creature that terrorizes a small coastal town, but this time it’s a crazed man-eating jellyfish?

Me: I hate you.

But ideas typically aren’t a problem for an author. I’ve got plenty of ideas. I just have no clue whether any of them will make good stories. I’ve started at least eight books that never made it past page 150. A few of them never made it past page ten. Some of them may grow into full novels one day, but I also wouldn’t be surprised if none of them did.

The question for me is, how should I get started on the next book? Do I need a breather to gather a bunch of new ideas and select the right one or should I plunge back into it and trust that the alchemy will produce something worthwhile?

Some authors, like Stephen King, stick to their word count every day no matter what. They force themselves to hunt down the muse and throttle it until it gives up the goods. Other authors, like Chuck Palahniuk, can take a year off to recharge and explore the world until the pressure builds up so much that they have to sit down and write the story. The muse tells them when the story is ready to go.

I think Stephen King’s process works well for “pantsers,” authors who don’t outline and write without knowing where the story will take them. But I don’t know how that can work if you are a “plotter” and you outline and research to see how a story fits together. How can you write to a word count that day if you haven’t plotted out how the next scene contributes to the story?

One technique that I’m trying was suggested by my agent. It’s called the List of Twenty. You come up with a list of twenty of ideas for a novel. The first ten or so will be obvious, so obvious that someone else may be having the same idea as you’re typing (which is why we end up with situations like two movies this year about the White House being taken over by terrorists).

But when you exhaust those first ten ideas, you start having to come up with more unusual and off-the-wall ideas, and that’s where you find the gold. Those are the ideas likelier to be unique and amazing.

Even then, you may still come up with an idea similar to someone else’s, but your spin on it might be so intriguing that it’s worth doing anyway (look at how Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games explored a different take on the kids-fighting-to-the-death scenario that Koushun Takami’s Battle Royale had already established).

After having completed six novels, I thought this process would have gotten easier. It hasn’t, and I don’t think it ever will. But when that inspiration does strike and the muse becomes your partner in crime, the exhilaration makes all of the struggle worth it. For me, that’s the thrill of the hunt.

The Most Important Thing Literary Agents Owe Their Clients

James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Confessions of an Editor

By Mark Alpert

For the first fifteen years of my journalism career I was a reporter for newspapers and magazines, but in 1998 I became a staff editor at Scientific American. This is a fairly typical career path because editor jobs usually pay a little better. (I’d like to emphasize the world “little.” Don’t go into journalism if you want to make a lot of money.) The new job involved some writing, but my primary responsibility was editing the magazine’s feature stories about breakthroughs in science and technology, most of which were written by the scientists who did the research. It was fun work because the topics varied so much. One month I learned all about metallic hydrogen; the next month I became an expert on the sex life of orangutans (which, by the way, is pretty damn fascinating, but that’s a subject for another blog post).

The stories were usually between 3,000 and 4,000 words, which were spread across six or eight pages in the magazine. Although most of the scientist-authors had extensive experience writing articles for research journals (such as Nature, Science, The New England Journal of Medicine, etc.), very few had written for a consumer magazine before. Therefore, the stories they submitted were full of terrible writing: lots of incomprehensible jargon, egregious overuse of the passive voice. On the other hand, the scientists were usually so delighted to be published in Scientific American — it was a big ego boost for many of them, and often a career boost as well — that they would tolerate heavy editing (and sometimes wholesale rewriting) with little complaint. And thus a monster was born.

I took the same attitude with the illustrations that accompanied the articles. I would draw them myself, in pencil, and fax my sketches to the artists. If their illustrations came back looking significantly different from what I’d drawn, I’d force them to do it over. I was drunk with power.

If we lived in an Old Testament kind of world, the gods of publishing would punish me for my sins. They would make sure that the people editing my novels were just as bad as I was. My editors would force me to rip out the heart of each book, to chop up the manuscript to the point where it became unrecognizable. But apparently I’ve been granted a dispensation. My editors have always allowed me to come up with my own solutions for fixing the problems in my drafts. And the process can be intensely gratifying, like working out your problems in therapy. There are lots of Aha! moments. “Of course! The answer is so simple!”

Reader Friday: Get Creative

The Dragon’s Pearl Critique – YA Fantasy Submission

My first page critique is a YA fantasy submission titled THE DRAGON’S PEARL. (Love the title!) My thoughts will be on the flipside. Enjoy!

Once upon a time, there was a girl named Misha who was neither kind nor beautiful, but very smart, and according to her mother, intelligence was all that mattered. For once, Misha had to agree because at this very moment, her immediate survival depended on her being very, very smart.

The gun dug against the small of her back. “Move faster,” the man holding the gun said. He wore a creepy-looking white mask—all three of her kidnappers did—and he had a real-looking black gun. He was smaller than the big man and stouter than the skinny one, with hairless arms smoother than her own. But since he held the one flashlight, Misha decided he must be the leader.

“Faster,” he said again.

She scooted down the tunnel, first in line. In case she sprung a trap, presumably. Designating a fourteen-year-old girl as a meatshield to catch all the arrows, it was the kind of thing she would consider.

“We’re almost there.” The kidnapper pushed past her, giddy like a sugar-overdosed child, darting his flashlight from wall to ceiling. “I can feel it.”

Where is there? Misha slowed her pace. She lifted both hands—handcuffed—to scratch her freckled nose. She had no idea where they were, what their purpose was. After removing her blindfold, they’d marched her down this abandoned subway tunnel for the past hour, twisting, turning, pausing, then picking a path less traveled.

The steel tracks were hard to see and easy to trip over. Her aunt had already tripped twice, with the big man there to catch her every time.

Her aunt Saria was the unfortunate tagalong to this kidnapping. She hummed tunelessly to herself, but Misha knew this was her aunt’s way of coping. Saria was afraid of everything, from plastic bags on the street that looked like dead cats to melodramatic fistfights on the movie screen. Violence terrified her.

“I’m sorry,” Misha said quietly. “If you hadn’t come to my tournament, you wouldn’t even be here.”

Saria sighed. “I wouldn’t have had to close my pawnshop for the day and lose all that profit.”

“Yes, that too.”

Saria barely winced when she smiled, her wrists raw from the nervous twisting of the plastic zip-ties. “There’s nowhere else I want to be, but by your side.”

My thoughts:

The “once upon a time” opener sounds cliché, but when it’s coupled with the twist of lulling the reader into the story as if it were a fable, only to spring into a kidnapping, the story keeps my interest. But the softer beginning diminishes the threat of the kidnappers. I’m not sure of the author’s intent. I don’t feel like Misha is in danger, especially once the aunt and the dialogue begin.

In the second paragraph, I got a little bogged down with the vague descriptions of the three men. There are not many lines there, but I don’t feel that it is important to detail the heights and weights of nameless men—especially since they are behind her. It’s like she has eyes behind her head and can see everything (while she is blindfolded, we later learn). When describing adversaries like these, it might be best to lump them together as threatening masked men and have their distinctive voices be the way she tells them apart, if that even matters so early in the story. If she’s blindfolded, she can only sense their presence by sound or smell. I would imagine that the smaller guy will play a definitive part in the story after he’s unmasked, but at this point, I don’t know that for sure. Only the author will know how important any of them will be.

I would like to see a dark world building setting play a part in this set up. That’s what makes fantasy great. This reads like an internal chapter scene and not the start of a book, perhaps because it doesn’t feel like Misha is in danger and the dialogue with the aunt. If she is to be the meat shield, I would like to feel that she appreciates the danger she is in and setting might help. She needs to be more wary and worried about what will happen to her and her aunt.

When Misha scratches her “freckled nose,” that took me out of the story. In her POV, she wouldn’t think of her nose as freckled. It would simply be her nose. That action trivializes the danger too. It’s a way for the author to get a character description in, but it also has the impact of diluting any threat.

Half way through the opener, we find out she has been blindfolded. That was not reflected in the first paragraphs. This reads as out of order to me. With her being bound and blindfolded, that would make it very awkward to walk, especially with her scooting down a tunnel. If she is blindfolded, the reader needs to see and feel this early on. She wouldn’t be leading the pack either. How would she know where to go?

I also didn’t know her aunt was even with her until well into the opener. Misha seems more worried for herself and not for her aunt, who would be in danger too. Plus their conversation does not translate the threat. It’s a bit chatty. And if violence terrified Saria, her humming a tune doesn’t seem appropriate, even if it’s a nervous tune. Plus when she’s more concerned about her profits for the day, that also diminishes the scary aspects of the scene.

The last couple of lines bounce into Saria’s POV. Misha can see her aunt wince and smile (if she is not blindfolded), but she can’t know how raw her wrists are, which tells me this is Saria’s POV. A head hopping thing.

The last thing I want to mention is the use of adverbs. Anything with an LY on the end is usually redundant and unnecessary if the rest of the action in the scene are well described. For example, “Misha said quietly” could be changed to “Misha whispered,” which would suggest she’s afraid of being overheard, but since the dialogue is a bit chatty, there is nothing she should be afraid of. If I were being kidnapped and had my aunt with me, I would be asking questions or trying to figure out where they were or how to get away.

When I first read through this, I thought it was okay. (I didn’t expect to be so picky.) I might keep reading to see where it goes, but unless you grip an editor or agent from this opener with something fresh, they will be looking for a reason to not turn the page. Focus on the danger more, make it eerie, and give a better glimpse into Misha’s personality and why she was chosen. Add elements of a mystery. That might make this opener better.

What do you think, TKZers?

What novelists can learn from song writers

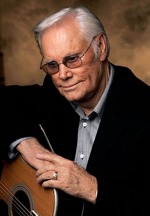

Last Friday, a giant in country music passed away. George Jones was not only considered by many to be the greatest country singer of all time, but also one of the most self-destructive. His string of hits was fueled by a private life of booze that was nothing short of  devastating. Once when his wife hid the car keys so he couldn’t go buy alcohol, he hopped on a riding lawn mower and rode it into town to the liquor store. He later parodied the story in a music video.

devastating. Once when his wife hid the car keys so he couldn’t go buy alcohol, he hopped on a riding lawn mower and rode it into town to the liquor store. He later parodied the story in a music video.

But despite the long chain of events that few mortals could survive, George Jones climbed to the top of the mountain and made a place for himself that will forever be the gold standard in country music.

His life was a soap opera that was mirrored in the songs he sang. His struggles with the demons of alcoholism are reflected in some of his album titles: “The Battle”, “Bartender’s Blues”, and the defiant “I Am What I Am”. But out of this self-inflicted carnage of a tragic life, one song emerged as arguably the greatest country song ever written: “He Stopped Loving Her Today”.

The song is performed with the singer telling the story of his "friend" who has never given up on his love. He keeps old letters and photos, and hangs on to hope that she would "come back again." The song reaches its peak with the chorus, telling us that he indeed stopped loving her – when he finally died.

It’s poignant, sad, and paints a heart-wrenching portrait of absolute love and devotion, as well as never-ending hope. Not only does it drill to the core of emotion, but it delivers the story with the few words.

So what does this have to do with writing books? Everything.

It’s called the economy of words—telling the most story with the least amount of text. It is an art form that songwriters must master, and novelists must study. There is no better example of the economy of words than in a song like ‘He Stopped Loving Her Today’. Not one word is wasted. No filler. No fluff. Remove or change a word from the song and the mental picture starts to deflate. The story is told in the most simplistic manner and the result is a masterpiece. Every word is chosen for its optimal emotional impact. Nothing is there that shouldn’t be. It is a grand study in how to write anything.

I’m not suggesting that your 100K-word novel be written with the intensity of George Jones’ song. In fact, if it were, it would probably be too overwhelming to comprehend. But my point is that no matter who you are—New York Times bestseller or wannabe author, your book contains too many unnecessary words. If you can say it in 5 instead of 10, do it. Get rid of the filler and fluff. Respect the economy of words. Less is more.

For those that love George Jones, enjoy this video. For those that have not heard “He Stopped Loving Her Today”, click the link, listen and learn.

He Stopped Loving Her Today by George Jones