By Joe Moore

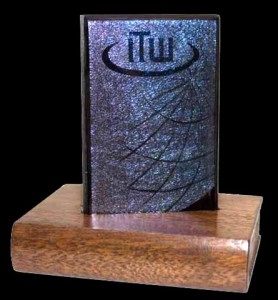

Yesterday, the nominees for the 2010 ITW Thriller Awards were announced. Congratulations to our Kill Zone blogmate, John Gilstrap! His thriller NO MERCY was nominated for Best Paperback Original. This is a great honor and we all wish John the best of luck in taking home that award next July.

Yesterday, the nominees for the 2010 ITW Thriller Awards were announced. Congratulations to our Kill Zone blogmate, John Gilstrap! His thriller NO MERCY was nominated for Best Paperback Original. This is a great honor and we all wish John the best of luck in taking home that award next July.

This past Sunday, Jim posted a blog about the importance of the opening pages of a manuscript submitted to an agent or editor. He pointed out some common pitfalls that new authors make, and which ultimately can result in rejection. Clare continued the theme on Monday by listing additional sins committed by first-time writers. And yesterday, Kathryn invited our visitors to submit the first page of their manuscript for a free critique. Unless otherwise requested, the authors will remain anonymous. So to start things off, here’s our first submission and my critique, page one of the manuscript THE CASSIOPEIA EFFECT

Marcus had never seen a dead body before. No, that’s misleading. He had seen a dead body—two of them in fact. That came with burying his wife and daughter eight years earlier. What he’d never seen before was a dead body lying in the streets. It was common enough in the part of the city he found himself living, where the homeless turned up dead from time to time, but up until a few moments ago, he’d been lucky.

It seemed his luck had changed. Whatever streak he’d been riding was coming to an end at an alarmingly fast rate. In the last twenty-four hours he’d lost a small fortune to his bookie, been given a notice of eviction from his apartment, and crashed his computer. Now there was a dead guy leaning against his car. It really didn’t surprise him, though.

For him, Good Luck came and went like a five dollar whore giving head while parked next to the curb. Bad luck, on the other hand, was like a bad love affair he couldn’t put an end to. No matter how many times it left, it always showed back up knocking at his door. All the other stuff had been Bad Luck knocking; finding the dead guy next to his car was it breaking down the door and rushing back into his life.

Marcus stepped off the curb and walked to his car and the waiting dead man. The filthy trench coat, ripped pants, and mismatched shoes left little doubt that the guy was one of the many homeless who wandered the streets. The amount of blood splattered across the car door made it pretty apparent the homeless guy was dead. But Marcus was still going to check. There was no way he was going to let a man die if there was still a chance to save him. He already had to live with too many things he wasn’t proud of and wasn’t about to add another.

Careful to avoid the blood pooled on the oil stained pavement, he knelt down next to the body, pulled back the collar of the coat with one hand, and with the other, checked for a pulse. Nothing. Whoever he had been, he was nothing but dead now. Marcus’ eyes played over the strange pattern of blood spray on the car door as he tried to decide what to do next.

There wouldn’t be any calls to 911 or the police. Moving him off the car and leaving him in front of his building for someone else to find wasn’t an option either. He didn’t need a dead guy connected to him in any way. What he could do, Marcus decided, was take him a few blocks where he’d be found and, hopefully, get the burial he deserved.

One of the main issues raised in Jim’s post on Sunday was what he called “Exposition Dump”. Unfortunately, that’s what we have in this example—the first 3 paragraphs contain a great deal of backstory with little “here and now”. This information should be saved and revealed later.

The best method for a reader to get to know a character is through their actions and reactions. Telling me about the bad luck Marcus has had does not engage me emotionally or spark my interest.

But all is not lost. In addition to cutting back on the “telling”, the writer might want to consider shifting the story into first person. Doing so could cause the reader to be pulled up close to the character and perhaps have a bit more feelings for Marcus. Here’s an example.

The first couple of sentences read:

Marcus had never seen a dead body before. No, that’s misleading. He had seen a dead body—two of them in fact. That came with burying his wife and daughter eight years earlier.

Now, here it is in first person:

I’d never seen a dead body before. No, that’s not true. Eight years ago, I had to bury my wife and daughter. But this was different.

Suddenly, the scene questions that pop into the readers mind—questions that were weak before—are now personal and tantalizing. The most intriguing: What happened to his wife and daughter? The straight exposition didn’t cause me to consider the questions in the same manner.

The second point I need to make is that if Marcos is the main character (and I have no idea if he is or not), I don’t like him very much. Why? He shows bad judgment. He’s into $5 whores, illegal gambling, and not willing to at least call the police—even anonymously—to report what he’s found. He quickly comes to the decision that for his own best interests, he should gather up the dead man and dump the body in another location. Granted, we don’t know why he would react this way, but having a number of negatives with little positive doesn’t make for a very likeable character. The reader needs to feel something for the character pretty much from the start. All I feel about Marcus is negative.

Don’t get me wrong. There’s nothing objectionable about a character with those attributes as long as there’s a reason for the reader to sympathize with him and respect or at least understand his judgment. Right now, there’s nothing here I was able to latch on to.

I like to use my “Dirty Harry” example of how to establish a reader/viewer and character relationship fast. The first scene of the movie, Harry helps a little old lady cross the street. Then he goes into a coffee shop that’s being robbed and blows the bad guy away. I like Harry right from the start even though I know he’s rough around the edges, dangerous, cocky, and kind-hearted.

The truth is that most manuscripts get rejected by the end of the first page—or at least the first couple of pages. This is reality. No agent is going to persevere for fifty or a hundred pages in hopes that things might get better. And no reader will either.

What I’ve expressed is my personal opinion. If I were an agent or acquisition editor, I would probably reject this manuscript and move on to the next one in line.

So what do you think? After reading the first page, are you compelled to read the second page?

Download FRESH KILLS, Tales from the Kill Zone to your Kindle or PC today.