Category Archives: The Stand

How Things Have Changed

Last Lines

By John Gilstrap

Over the years, we’ve devoted a lot of space here at The Killzone to the importance of first lines, but in the grand scheme of things, I spend far more time in my own writing fretting over the last line. I’ve lost track of the books that have held me solidly in their spell all the way till the last couple of pages, only to betray my devotion by short-changing me on the ending. I vow never to do that.

As a writer of thrillers, I think it’s my job to give my readers a wild ride, filled with exciting twists. I work hard to make my characters seem alive to readers, and I’m often harder on the good guys than I am on the bad guys–at least for a while. I owe it to my readers to bring the story to a satisfying ending. That doesn’t mean that I promise a “happy ending” necessarily, but I do guarantee a sense of peace when the journey is over. It’s the kind of commitment that I think breeds trust between a writer and his readers.

Now that I’m writing a series, I face the additional challenge of leaving enough of a cliffhanger to compel readers to look forward to the next book without also incurring their wrath by making them feel baited and switched. To pull all of that off within the time constraints of my contract, I have to know the point to which I am writing the story.

All too often these days, I read books by brand name authors who seem to end their books by running out of words. The plot develops, climaxes and then . . . I’m at the back cover. One of the most egregious examples in recent years is John Grisham’s A Painted House. I actually wondered if I had picked up a defective book where the last chapter had been removed. Don’t get me wrong: I think Grisham is a great story teller, and as I read it, I thought that House was one of his best. And then . . . thud.

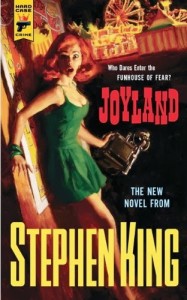

An even more famous example is Stephen King’s The Stand. There I was plowing through hundreds of thousands of words, loving it, loving it, loving it, and . . . what are you kidding me??

Here’s the thing about this three-act structure most of us adopt in our writing: A story had a beginning, a middle and an end, and each part is equally important. There’s no room for laziness. Every component of every scene needs to pull the reader forward. The last scene is most important of all, I think, because that’s what the reader will remember forever.

I haven’t always gotten it right, either–at least not if you read some of the letters I’ve gotten over the years. Nathan’s Run in particular has generated a number of letters from fans who wanted one more chapter. In fact, the chapter they craved was in my original draft. I took it out and reinserted it four or five times before I decided to leave it in the drawer. Without giving too much away, I thought–and I still think, but am less sure–that the story ended when the action ended, and that the final feel-good knot-tying chapter was a step too far.

Of course, I’m the curmudgeon who believes that JK Rowling’s biggest misstep in the largely-wonderful Harry Potter saga is the final chapter–the coda, really–of The Deathly Hallows. I would rather have imagined the future instead of having it spelled out for me. It didn’t ruin anything for me; it just felt like one too many bits of storytelling.

What do y’all think? Any favorite endings out there? Terrible ones?

For me, the best closing line ever written, bar none, comes from To Kill A Mockingbird: “And he’d be there when Jem waked up in the morning.” It tells us everything we need to know, and let’s us just float on the satisfaction of time well spent.