@jamesscottbell

In April, 1917, a puckish, fun loving nineteen-year-old Marine named Frederick Hamilton “Ted” Fox was about to be shipped off to France. His mother, Esther, and sister, Frederica (whom everyone affectionately called “Freddy”) came to the train station to see him off.

Ted Fox was my great uncle. In the photograph below I hope you can see the expressions on the faces. Ted, I am told, had a generous and robust spirit, and a smile that could light up a room. Esther looks so proud of him. And my great aunt Freddy has the most engaging, vivacious and interested look about her. She was an artist, and in those heady days just before the Roaring 20’s she had an artist’s temperament about living life to the full. They all came together in this amazing photo:

Corporal Ted Fox arrived in France and began preparing for action. It came in June of 1918, in what came to be known as the Battle of Belleau Wood.

At dawn on June 7th, the Marines were ordered to advance toward the German lines and their deadly machine gun nests.

The first wave ended in slaughter.

Ted Fox’s squad, along with another, were dispatched to flank the nests. They cleaned out one, and went for another. It was during this second wave that Ted Fox, leading his men, was killed by a bullet to the head.

News traveled slowly in those days, and it took nearly six months for Esther to receive the final news of her son’s sacrifice. She’d written a letter to a naval hospital and that letter was seen by a wounded soldier. He took it upon himself to write to her.

Great Lakes, Ill.

February 15th, 1919

Dear Friend Mrs. Fox- – –

My attention was called to a letter you wrote the hospital in relation to your son who was killed in action. He was in the same company and platoon that I was. I did not see your son fall but I assure you that he fought gallantly for his country and died upon the field of battle bravely. I’m sure his last thoughts were of his dear Mother at home and praying that the news of his death would not be too great a shock to her. As being in battle I know that one thinks of his dear ones at home and not of what may happen to oneself. We all knew that we were either going to be killed or wounded in such a terrific battle that was then raging but all faced it bravely and fought fiercely until we fell. I was wounded severely but escaped with my life in the same battle that your son was killed . . .

Mrs. Fox, I know that you are and should be very proud to be a mother of such a son that volunteering gave his life to his country.

All the boys that died on the field of battle will never be forgotten and shall be honored by their comrades.

A Marine,

Private Roy R. Drowty

U.S. Naval Hospital

Great Lakes, Ill.

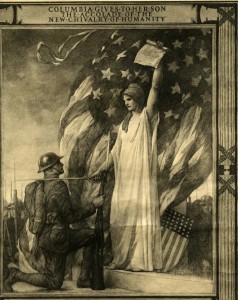

As a memorial, Esther Fox was given a specially commissioned piece of art, showing the female symbol of America, Columbia, honoring the war dead. At the top it says: COLUMBIA GIVES TO HER SON THE ACCOLADE OF THE NEW CHIVALRY OF HUMANITY.

This memorial now hangs in my home.

And when my dad, Arthur Scott Bell, was born in 1919, the family decided to nickname him Ted, in honor of his uncle. In a way, my dad was a living memorial to Ted Fox. And he carried that legacy with him when he went into the Navy in World War II.

I believe in memorials. I believe we have to remember sacrifice. If we don’t, if we give up on the idea of honoring those who gave “the last full measure of devotion” for our greater good, we will not only lose what’s best in America but also what’s best in the human spirit.

War is hell. And young men and women, wave after wave of them, have gone into hell for us. I don’t care what side of the political spectrum you come from. Each of us owe our war dead and wounded all the honor we can bestow. They’re not politicians or pundits. They’re the brave ones who’ve been there for us, no matter what we believe. In fact, so that we can continue to believe what we want and talk about it, demonstrate about it, vote on it.

The line in Private Drowty’s letter that stands out for me is this one: We all knew that we were either going to be killed or wounded in such a terrific battle that was then raging but all faced it bravely and fought fiercely until we fell.

That’s why we need to remember.

In the last stanza of Lt. Col. John McCrae’s World War I poem “In Flanders Fields” (referring to a place where war dead were buried) we, the living, are given a charge. I pray you will take a moment to think about it before you dive into your beer and hot dogs this Memorial Day weekend:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.